James Webb telescope reaches 'perfect' alignment ahead of debut science images

The telescope's first science images drop in July.

All four science instruments on NASA's James Webb Space Telescope have achieved "perfect alignment" in advance of the telescope's official debut this summer, project officials said in a news teleconference on Monday (May 9).

"I'm delighted to report that the telescope alignment has been completed with performance even better than we had anticipated," Michael McElwain, James Webb Space Telescope project scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland said, according to CBS News. "We basically reached a perfect telescope alignment. There's no adjustment to the telescope optics that would make material improvements to our science performance."

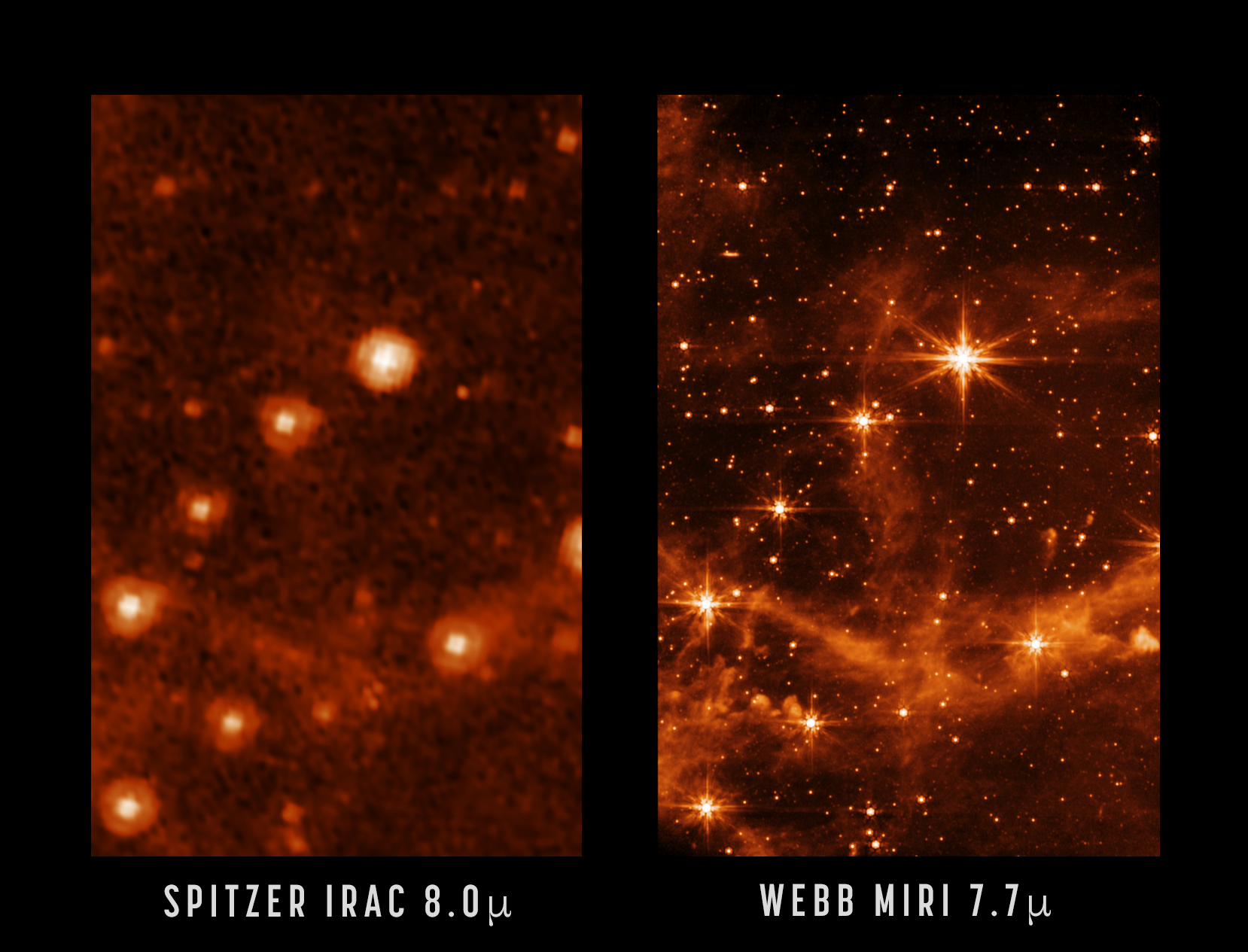

To illustrate the telescope's readiness, NASA shared a teaser image taken by Webb's Mid-Infrared Instrument, or MIRI. The new image shows a side-by-side comparison of observations of a nearby galaxy taken by Webb, versus observations of the same galaxy taken previously by NASA's now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope.

Related: In a historic launch, the Webb Telescope blasts off into space

While the Spitzer image shows a blur of seven or so nearby stars located in the Large Magellanic Cloud (a satellite galaxy that orbits the Milky Way), the Webb image of the same region captures the foreground stars in sharp detail, offset by wispy clouds of interstellar gas and hundreds of background stars and galaxies, captured in what NASA calls "unprecedented detail."

With its instruments aligned, the Webb telescope awaits a final instrument calibration before it officially begins studying distant stars later this summer, NASA said. In July, the telescope will share its first suite of science images, targeting galaxies and objects that "highlight all the Webb sciences themes ... from the early universe, to galaxies over time, to the life cycle of stars, and to other worlds," Klaus Pontoppidan, Webb project scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said in the news briefing.

NASA launched the $10 billion Webb telescope on Dec. 25, 2021, sending the telescope on a 930,000-mile (1.5 million kilometer) journey to its final position in the sky. The telescope is composed of 18 hexagonal mirror segments, fitted together into one large, 21-foot-wide (6.4 m) mirror. The design allowed the telescope's mirror system to be folded inside a rocket at launch — unlike Webb's predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope, which has just one primary mirror that measures about 7.8 feet (2.4 m) across, Live Science previously reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists predict that Webb will be able to image distant objects up to 100 times too faint for the Hubble Space Telescope to see. The telescope was designed to observe the dim light of the earliest stars in the universe, dating to about 13.8 billion years ago — just millions of years after the Big Bang.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.