Is Nazi gold real?

Some loot from World War II may still be undiscovered.

As Nazi forces tore through much of Europe and North Africa during World War II, gold, valuable artifacts and priceless paintings disappeared from the conquered territories, and many of these treasures are still missing to this day. Many people believe the Nazis hid these treasures away in secret locations. It's perfect fodder for urban legends: the loot stashed away by Nazi soldiers, its location only revealed on a difficult-to-obtain map. But are the tales true? Does gold stolen and concealed by the Nazis really exist?

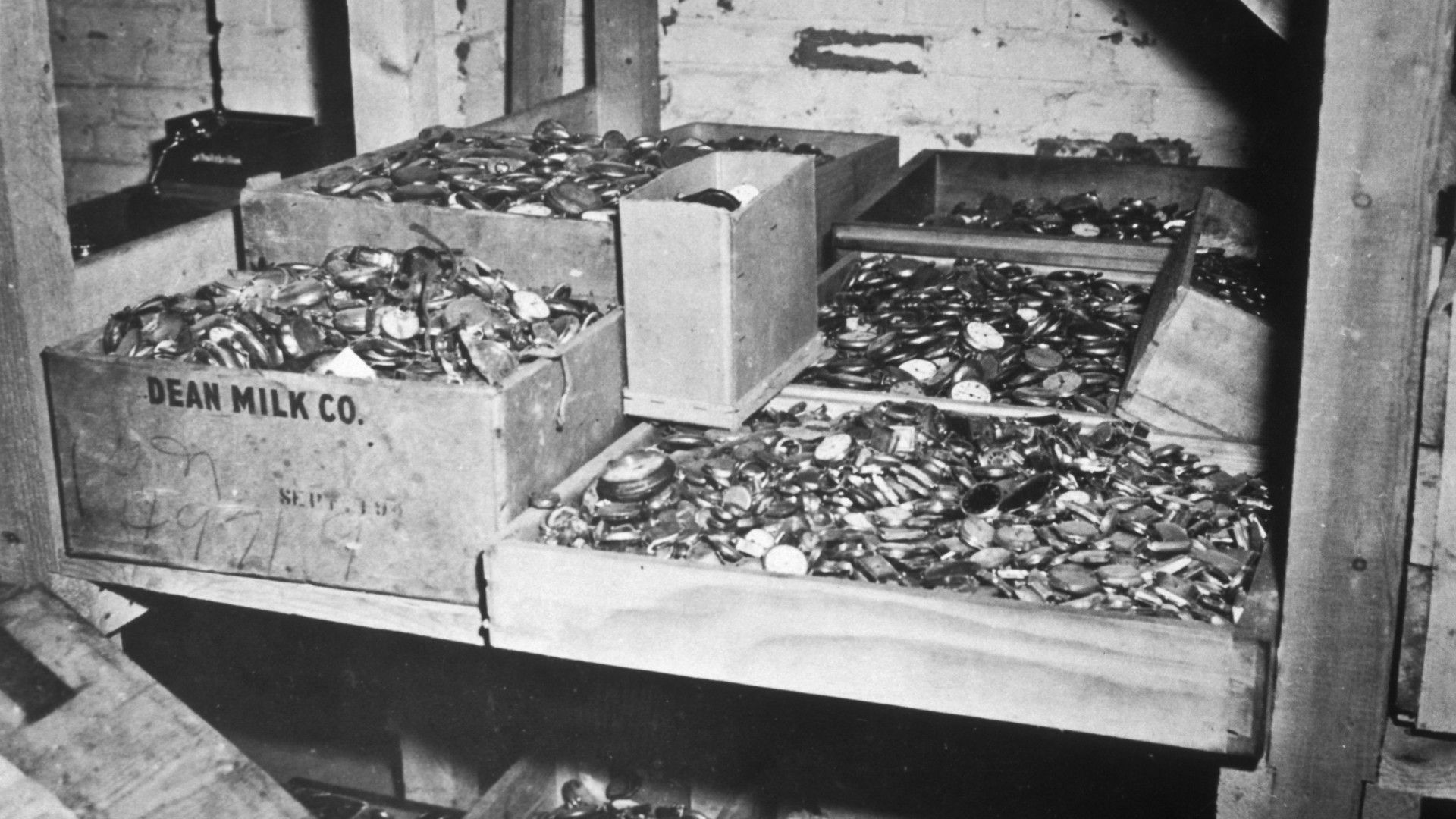

The answer is yes: Not only is Nazi gold real, it was a driving force in paying for Hitler's regime. As Nazi forces spread across Europe, their policy was to loot their victims' valuables, largely from the Jews. This included fine art, jewelry, Oriental rugs, silverware, porcelain and glass. But the most important item, economically, was gold.

Nazi gold is an umbrella term. It includes both monetary gold, which is held by governments in central banks as part of their currency reserves, and valuable items stolen from individuals (often not gold at all). "Monetary gold is gold that Germans seized from central banks belonging to the state," Ronald Zweig, professor of Israel studies at New York University, and author of "The Gold Train: The Destruction of the Jews and the Looting of Hungary" (William Morrow, 2002), told Live Science. "This is not stuff stolen from individual private victims. We know that the Germans stole the monetary gold reserves of all of the national banks of the countries they occupied, and only 70% of that money was restored after the war."

Typically, the Nazis seized monetary gold and stored it in central depositories, and then used it to finance the Nazi war effort. But the Nazis also looted gold from individuals. "Non-monetary gold was derived from looting the homes, possessions and even the bodies of the victims," Zweig wrote in his book. Much of what was looted from private individuals was either lost or seized at the end of the war.

Related: Which is rarer: Gold or diamonds?

In 1945, U.S. Army units unearthed hidden hoards of loot across Germany and Austria. The most spectacular discovery was the Merkers salt mine in Thuringia, Germany, which contained gold bullion, coins and currency worth $517 million in 1945 values (around $8.5 billion today). As Allied forces took control of occupied territories, an effort was made to redistribute the monetary gold to the countries it was seized from, according to Zweig. Some of the loot that had been seized from individual victims was auctioned off to the public. But other recovered treasures were sold and the proceeds were given over to organizations created to help Jewish refugees in the wake of the war, according to Zweig.

The total value of gold and other assets looted by the Nazis remains uncertain. The initial reports of loot "created an El Dorado in Central Europe," Zweig wrote in his book. Many people believe that not all of the caches of looted gold have been discovered, leading to the current wealth of urban legends on the subject. But Ian Sayer, a British World War II historian and co-author of "Nazi Gold: The Sensational Story of the World's Greatest Robbery - and the Greatest Criminal Cover-Up" (Congdon & Weed, 1985), remains skeptical when such stories surface in the media.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the unauthenticated "Michaelis" diary — supposedly written by a Waffen Schutzstaffel (SS) officer using the pseudonym "Michaelis" — was first reported in 2020, it purpotedly revealed 11 sites where Nazis concealed looted gold, jewels, priceless paintings and religious objects. Following the discovery, Sayer investigated this dairy and its claims. The diary was supposed to belong to the SS officer Egon Ollenhauer, but no such name was ever registered in the SS officer lists, Sayer told Live Science.

Another commonly-reported story is the the location of the Wałbrzych gold train purportedly containing a hoard of Nazi gold. The train was claimed to be buried inside a mountain in southwestern Poland. When the location was supposedly discovered, Sayer immediately dismissed the claim as "absolute rubbish." After extensive excavation of the site in August 2016, no gold and no train were uncovered.

Ronald Zweig's book "The Gold Train" tells the story of a real gold train, which left Budapest full of looted Nazi gold, jewelry and silver that was stolen from Hungarian Jews. The train was headed for a Nazi stronghold somewhere in the Alps. The train halted in Böckstein, Austria, hidden in the Tauern tunnel. Some loot was taken and buried in various sites across Tyrol (a western Austrian state) and in Feldkirch (a medieval town in western Austria), and subsequently uncovered by local farmers and the French military after the war ended. The loot on the train was seized by the U.S. armed forces in May 1945. But some of the hidden loot has never been uncovered.

Related: What was the deadliest day in US history?

Sayer claims to be the only person to have tracked down missing Nazi gold since the initial repatriation efforts at the end of the war. Rather than a buried cache of loot, however, he tracked down two gold bars belonging to the Nazi Reichsbank, the central bank of the German Reich until 1945.

By studying records that documented the movement and storage of gold immediately after WWII, Sayer located the two bars of gold in a bank vault owned by the Deutsche Bundesbank. They were held in the account of an unnamed individual, and, over two decades, U.S. government officials repeatedly denied knowledge of the whereabouts of the two gold bars in their correspondence with Sayer, according to his book. U.S. military authorities issued a detailed report which listed the two gold bars in a vault in U.S. custody in the Munich Land Bank, and, even though a later report mistakenly declared them missing, they remained in the same vault, according to an article later published in the Bank of England's staff magazine.

However, the Tripartite Commission for the Restitution of Monetary Gold (TGC), which had been set up in 1946 to recover gold stolen by Nazi Germany and return it to its rightful owners, could not complete their work until all Nazi gold on record had been returned. The whereabouts of the two gold bars were then publicly disclosed in 1997.

Prior to the London Conference on Nazi Gold that year, which aimed to finalize the work of the TGC, the Bank of England released a statement disclosing the exact amount of gold it was holding on behalf of the TGC, as well as two gold bars. The published that year in the Bank of England's staff magazine identified them as the two gold bars that Sayer had tracked down and charted their history. They had been transferred to a Bank of England vault in 1996 after an investigation by the TGC and remain there to this day. A representative of the Bank of England arranged for Sayer to visit the vault and view the gold himself in view of his efforts.

Sayer turns down several requests every year to join treasure-hunting expeditions looking for Nazi loot. "Yes, I'm sure there are caches [of undiscovered loot]", he said, but "I don't think there's anything left where you've got a map where X marks the spot."

Originally published on Live Science.

Martin McGuigan is an Irish writer based in Norwich, England. His work has appeared in The Mays XIX, Cabinet of the Heed and SHE magazine. His writing explores the bizarre questions of everyday life, the mysteries of human psychology, and environmental issues. He studied English literature at the University of Cambridge and creative writing at the University of East Anglia.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus