Astronomers plan to fish an interstellar meteorite out of the ocean using a massive magnet

The meteorite fell to Earth in 2014.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers are planning a fishing trip to land an extraterrestrial interloper on Earth: A small meteorite from another star system that crashed into the Pacific Ocean with energy equivalent to about 121 tons (110 metric tons) of TNT.

The team, from Harvard University, hopes to find fragments of this interstellar rock — known as CNEOS 2014-01-08 — which slammed into Earth on January 8, 2014.

"Finding such a fragment would represent the first contact humanity has ever had with material larger than dust from beyond the solar system," Amir Siraj, an astrophysicist at Harvard University and the first author of a new paper published on the non-peer reviewed pre-print service ArXiv on CNEOS 2014-01-08, told Live Science in an email.

Siraj identified the object's interstellar origin in a 2019 study with 99.999% confidence, but it wasn't until May 2022 that it was confirmed to Siraj by the U.S. Space Command. There are no known witnesses to the object striking Earth.

"It struck the atmosphere about a hundred miles [160 kilometers] off the coast of Papua New Guinea in the middle of the night, with about 1% the energy of the Hiroshima bomb," Siraj said.

Related: What are the largest impact craters on Earth?

Measuring just 1.5 feet (0.5 m) wide, CNEOS 2014-01-08 now appears to have been the first interstellar object ever discovered in our solar system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Previously, an oblong object called 'Oumuamua held that title. Discovered in 2017 during the Pan-STARRS sky survey, the space rock zipped through our solar system at nearly 57,000 mph (92,000 km/h), and later, Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb, a colleague of Siraj, claimed it might be an alien machine. 'Oumuamua's discovery was followed in 2019 by comet 2I/Borisov, the first interstellar comet, which was spotted by amateur astronomer Gennadiy Borisov in Crimea.

CNEOS 2014-01-08 is thought to be from another star system because it was traveling at 37.2 miles per second (60 kilometers per second) relative to the sun. That's too fast for it to be bound by the sun's gravity.

"At the Earth's distance from the sun, any object traveling faster than about 42 kilometers per second [26 miles per second] is on an unbounded, hyperbolic escape trajectory relative to the sun," Siraj said. "This means that CNEOS 2014-01-08 was clearly exceeding the local speed limit for bound objects [and] it didn't cross paths with any other planets along the way, so it must have originated from outside of the solar system."

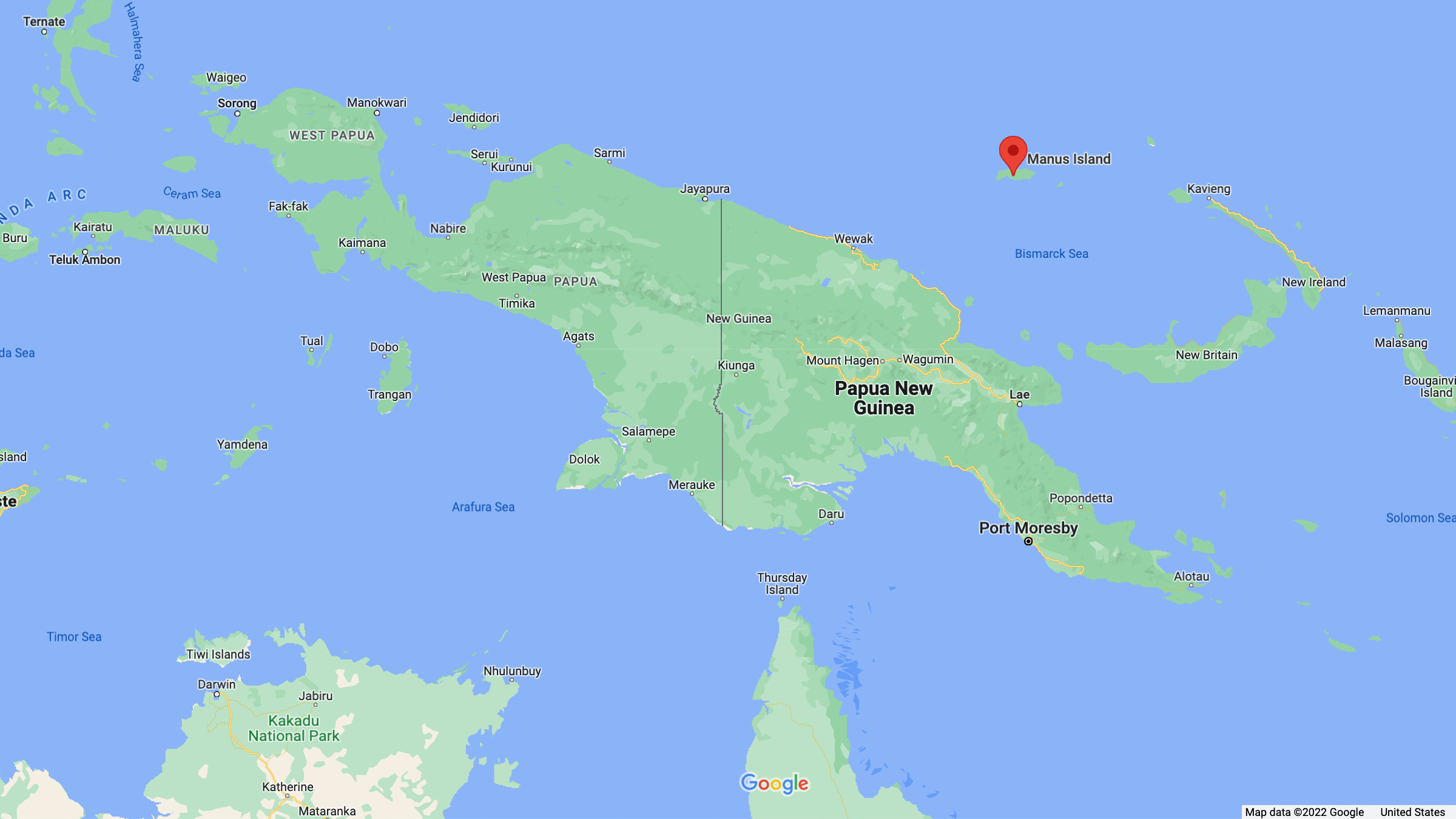

Cut to Siraj and Loeb's Galileo Project, a $1.6 million expedition to lower a magnet similar in dimensions to a king size bed at 1.3 degrees south, 147.6 degrees east, the U.S. Department of Defense's location of the meteorite's resting spot. That's about 186 miles (300 km) north of Manus Island in the Bismarck Sea in the southwest Pacific Ocean.

CNEOS 2014-01-08 greatly exceeded the material strength of a typical iron meteorite, which should make it even easier to recover, according to Siraj. Material strength refers to how easily something can resist being deformed or damaged by a load. "Most meteorites contain enough iron that they will stick to the type of magnet we plan on using for the ocean expedition," he said. "Given its extremely high material strength, it is very likely that the fragments of CNEOS 2014-01-08 are ferromagnetic."

Leaving from Papua New Guinea, the Galileo Project's ship would use a magnetic sled on a longline winch, which will be towed along the seabed at 1 mile (1.7 km) for 10 days. It's hoped the magnet can recover tiny fragments of the meteorite, measuring as small as 0.004 inches (0.1 mm) across.

However, it's unclear when the astronomers will be able to mount their expedition. The Galileo Project already has $500,000 committed, with a further $1.1 million required to make it a reality. That's good value compared to a space mission, according to Siraj.

"The alternative way to study an interstellar object at close range is by launching a space mission to a future object passing through the Earth's neighborhood," said Siraj, who with Loeb is also working out the details of such a mission should another object like 'Oumuamua appear in the solar system. "But that would be 1,000 times more expensive at about $1 billion."

Originally published on Live Science.

Jamie Carter is a Cardiff, U.K.-based freelance science journalist and a regular contributor to Live Science. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and co-author of The Eclipse Effect, and leads international stargazing and eclipse-chasing tours. His work appears regularly in Space.com, Forbes, New Scientist, BBC Sky at Night, Sky & Telescope, and other major science and astronomy publications. He is also the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus