World’s largest iceberg is getting swept away from Antarctica to its doom, satellite image shows

A new satellite image shows that the world's largest iceberg, A-76A, has entered the Drake Passage, a waterway that contains a fast-moving ocean current that will send the mighty berg on a one-way trip to its watery grave.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

After slowly drifting around Antarctica for more than a year and barely melting, the world's largest iceberg could soon be set on an accelerated course toward its eventual demise, a new satellite image reveals.

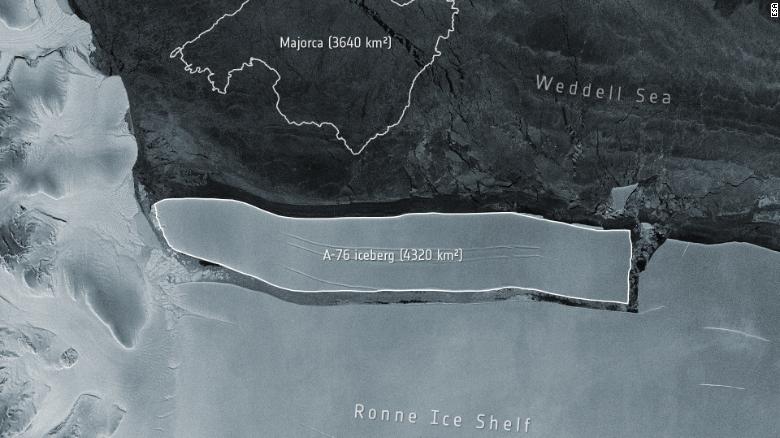

The gargantuan ice slab, known as A-76A, is around 84 miles (135 kilometers) long and 16 miles (26 km) wide. It is the largest fragment of the world's previous biggest iceberg, the Rhode Island-size A-76, which broke off from the western side of Antarctica's Ronne Ice Shelf in May 2021 and later fractured into three chunks: A-76A, A-76B and A-76C.

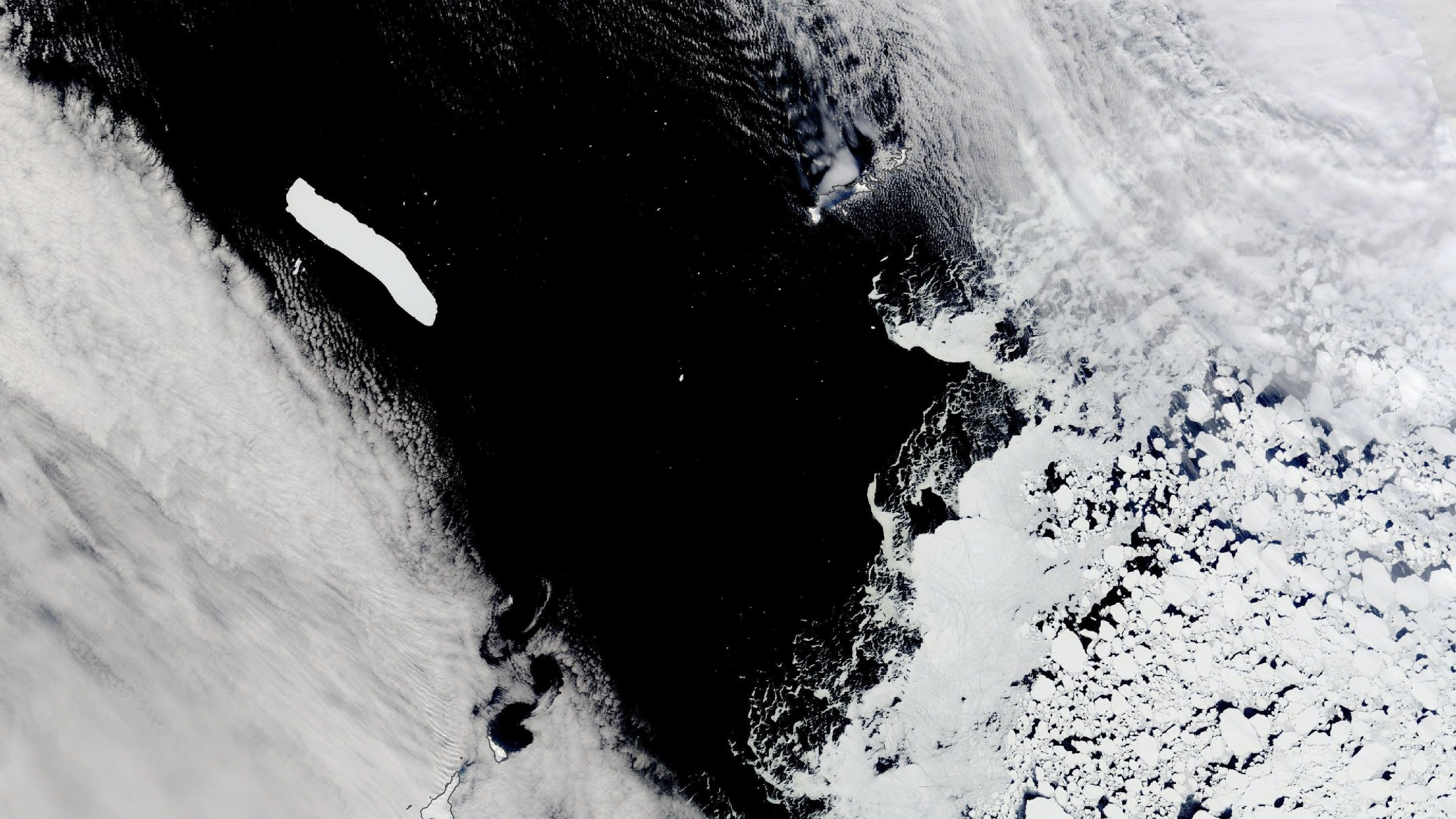

On Oct. 31, NASA’s Terra satellite captured a photo of A-76A floating in the mouth of the Drake Passage, a deep waterway that connects the Pacific and Atlantic oceans between Cape Horn in South Africa and the South Shetland Islands to the north of the Antarctic Peninsula. The image shows that the girthy berg is currently sitting between Elephant Island and the South Orkney Islands (both obscured by clouds in the image) at the southern end of the passage, but its trajectory hints that it will head further north into the waterway in the coming weeks. The image was released online Nov. 4 by NASA's Earth Observatory.

Normally, when icebergs drift into the Drake Passage they are quickly dragged eastward by strong ocean currents, before being whipped northward into warmer waters, where they completely melt soon after, according to Earth Observatory.

Related: Arctic 'ghost island' that vanished may have actually been a dirty iceberg

To date, A-76A has traveled around 1,250 miles (2,000 km) since breaking off from the Antarctic Peninsula in 2021. The berg has managed to avoid substantial ice loss during its journey so far. Data collected by the U.S. National Ice Center in June revealed that A-76A is almost exactly the same size as it was when it fractured from its parent berg more than a year ago, according to Earth Observatory.

However, it is unlikely to remain intact much longer because the Drake Passage is renowned for sending icebergs on a one-way trip to their watery graves. The main reason for this is the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC); it's the only current that flows entirely around the globe, and it contains more water than any other current on Earth. The ACC, which runs from west to east through the Drake Passage, transports between 3,400 and 5,300 million cubic feet (95 and 150 million cubic meters) of water every second, according to Britannica. As a result, wandering bergs that enter the Drake Passage are swiftly dragged away from the Antarctic and dumped in warmer waters, where they soon melt away.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ACC is not the only ocean current that helps determine the fate of icebergs. Other smaller currents also play a key role in the distribution and eventual destruction of the wandering ice masses, but researchers are still trying to understand exactly how.

On Oct. 19, a study in the journal Science Advances revealed that another record-breaking berg, A68a, which held the title of the world's largest iceberg for around three years, was ripped in half by powerful ocean currents after narrowly avoiding a potentially catastrophic collision with South Georgia Island in late 2020. At the time, researchers were surprised when the mighty berg suddenly fractured in the middle of the ocean. But the study revealed that a sudden shift in the direction and strength of nearby currents was to blame for the massive iceberg's breakup.

It is currently unclear how long A-76A will remain in the Drake Passage, where it will end up, and how long it will survive once turbulent currents fling the ice mass northwards.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus