Do any infectious diseases have a 100% fatality rate?

Researchers have made great strides to prevent deaths from fatal diseases, but the cures for some of them still elude us.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Infectious diseases make up three of the ten slots in the World Health Organization's top 10 causes of death and account for millions of deaths annually across the globe. Despite these high numbers, however, diseases like COVID-19 and tuberculosis don't kill the majority of people they affect: COVID-19 kills an estimated 1% of those infected, based on totals reported by the World Health Organization (WHO), and tuberculosis kills fewer than 15%, according to WHO reports.

But do any infectious diseases have a 100% fatality rate? And if so, what makes them so deadly?

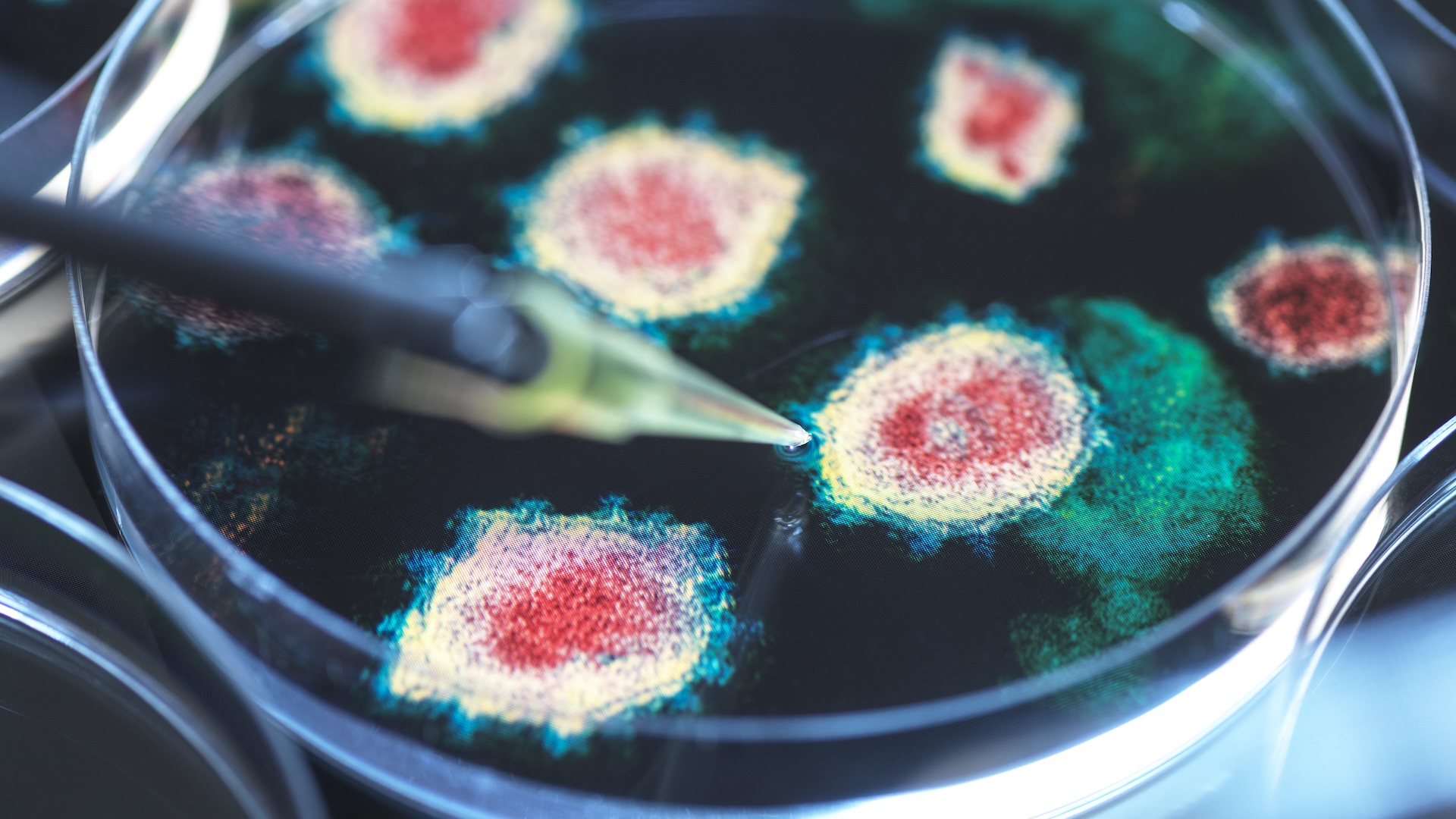

Infectious diseases are caused by pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites. According to Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, nearly all the infections that once had a 100% fatality rate can now be prevented with vaccination or treated with modern medicine.

For example, HIV infections can now be treated with medications that extend people's lives and stop the disease from progressing to AIDS. Smallpox, some rare variants of which were nearly 100% fatal, is now eradicated across the globe. Death from rabies, which is nearly 100% fatal once symptoms appear, can be almost entirely prevented with immediate medical care after exposure. This care includes washing the wound, getting a rabies vaccine and, sometimes, getting antibodies against the rabies virus.

"Things that are 100% fatal [if left untreated] have become manageable because of human ingenuity," Adalja told Live Science.

However, there are a few fatal infectious diseases that we still haven't cracked. Some of these are always or nearly always deadly, while others just have very high fatality rates.

Related: Why do we develop lifelong immunity to some diseases, but not others?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For example, amoebic meningitis — better known as a "brain-eating" amoeba infection — is a rare infection that is nearly always fatal. Amoebic meningitis spreads to the brain through the nose, usually after a person is submerged in contaminated water. In rare cases, these infections have been successfully treated but scientists are hunting for better solutions.

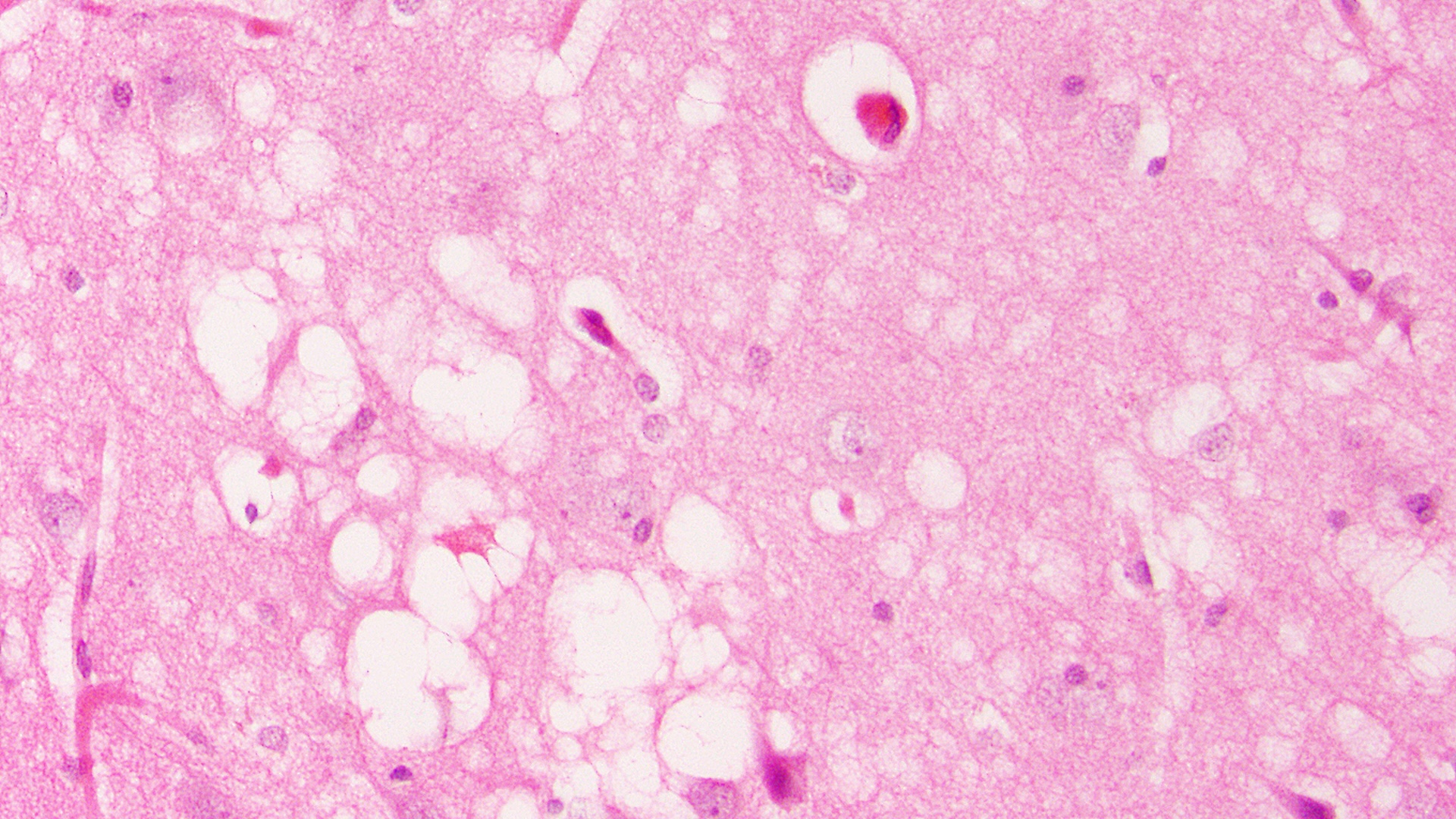

And there are other, rare diseases that still remain a mystery, such as prion diseases. These diseases are caused by misfolded proteins in the brain — called prions — which cause other proteins to misfold in a chain reaction that ultimately causes brain damage and death.

Most prion disease cases would not be considered infectious; they stem from genetic mutations that are inherited or arise spontaneously. However, people can rarely develop them after eating meat contaminated with prions or being exposed to them during medical procedures. Examples include variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD), which people can get after consuming beef from cows with "mad cow disease," and Kuru, which famously affected the Fore people in Papua New Guinea.

"Prions have been looked at for decades, but I think they're still trying to figure out what the ultimate trigger is there," said Rodney E. Rohde, an infectious disease specialist at Texas State University. Although they are extremely rare, prion diseases all have one thing in common: Once you get them, there is no cure, and death can often occur within weeks of symptoms beginning to show.

What makes diseases like these so fatal? One factor is the disease's evolutionary history. If a disease has infected human hosts for tens of thousands of years, our bodies have the opportunity to try to build up a defense to it, which increases our odds of survival. However, if humans are an accidental, or dead-end host — as is the case for diseases like rabies — the disease isn't built to keep us alive, as we aren't its main hosts. In those cases, we usually haven't developed a suitable immune response to fight it without the help of medical treatment.

Rabies, for example, does engender an immune response in humans, but the response is not fast enough to defeat the virus before it infects the brain and kills the host. "Some pathogens have way more of a diabolical and notorious nature," Rohde told Live Science. "They flood the immune system so the body can't adapt quick enough."

Katherine Irving is a freelance science journalist specializing in wildlife and the geosciences. After graduating from Macalester College, where she wrote screenplays, excavated dinosaur bones and vaccinated wolves, Katherine dove straight into internships with Science Magazine and The Scientist. She now contributes to the Science Magazine podcast and loves reporting about the beautiful intricacies of our planet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus