'Flow state' uncovered: We finally know what happens in the brain when you're 'in the zone'

Researchers say they've found the answer to competing hypotheses about how the brain functions in a "flow state."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Many people know the feeling of being "in the zone": As they're fully immersed in a task, the background noise of the world fades and they may not notice time passing. Gymnasts may enter this all-consuming mental state as they're refining a floor routine, an artist might find "the zone" when adding delicate brushstrokes to a painting and a writer might enter it as they're crafting the climax of a chapter.

This state, known in psychology as a "flow state," is pursued by those who want to be more productive and creative in an enjoyable way. What happens in the brain during this state, however, has been under debate for more than four decades.

Now, in research published March 4 in the journal Neuropsychologia, scientists may have settled the debate. They conducted a new brain-scan study that has finally revealed which regions of the brain are activated in the midst of a creative flow state.

Their findings contradict one popular theory of flow while supporting another, and they seem to reveal the key ingredients needed to get "in the zone."

Related: What happens in our brains when we 'hear' our own thoughts?

The competing hypotheses of flow

Two brain networks have historically been studied during tasks that could unlock flow. One is the default mode network (DMN), a circuit of connected brain areas associated with daydreaming whose activity spikes when people are not engaged in a specific task. The second is the executive control network (ECN), which supports complex cognitive processes, like problem-solving, and tunes out distractions.

Both networks can act independently, but they've also been shown to display certain levels of connectivity and to interact dynamically, especially during the creative process.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers have proposed two main theories for how the flow state affects the brain. The first posits it's a state of hyperfocus in which ECN activity increases and guides the DMN to maintain focus on a task, to help generate relevant ideas, said Dmitri van der Linden, a professor of work and organizational psychology at Erasmus University Rotterdam who was not involved in the new study.

"It has been hypothesized that during flow, which is characterized by an intense task focus, DMN activity is relatively low," van der Linden told Live Science in an email. DMN activity is linked to "creative production," though, which is needed to generate ideas and improvise, he noted. With that in mind, this first hypothesis implies that both the ECN and the DMN are active and play off each other during flow, respectively contributing attention and creativity.

The alternative theory of flow, however, says that the expertise a person gains in a task through practice forges its own neural processing network that does not require ECN supervision or DMN involvement.

If you don't know, you can't flow

To pit these hypotheses against each other, John Kounios, a professor of psychology at Drexel University and senior author of the study, and his team studied 32 jazz guitarists, some highly experienced and some less-experienced. Creative tasks like improvisational jazz lend themselves well to triggering a flow state.

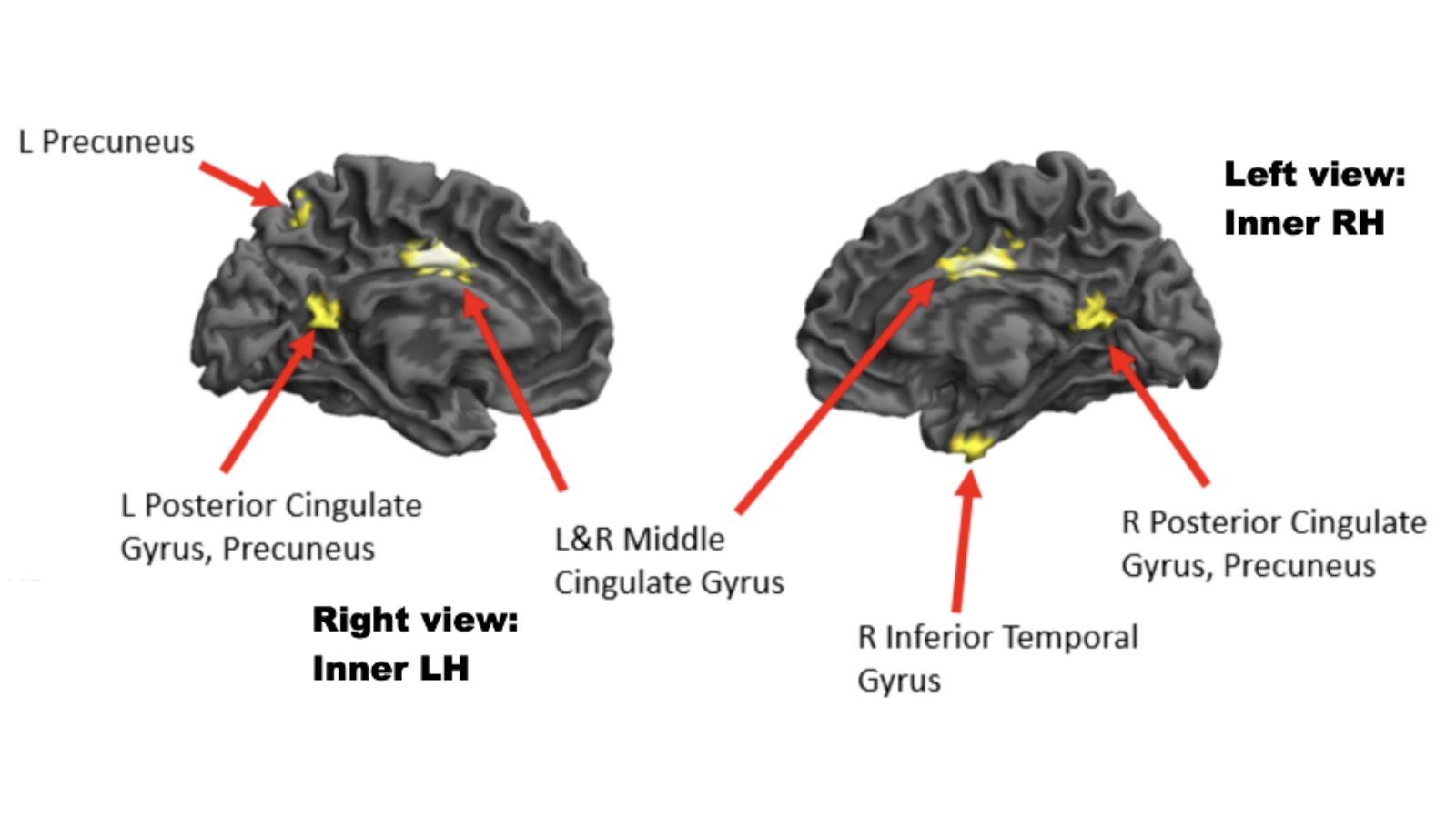

The researchers scanned the musicians' brains using electroencephalogram caps, fitted caps studded with electrodes that track the brain's electrical activity. They examined activity in areas related to the DMN and the ECN and compared flow and non-flow states, which they evaluated with a questionnaire about the musicians' experiences while improvising.

Experienced musicians in a flow state showed decreased activity in the ECN and the DMN and increased activity in regions that process auditory, visual and movement information. This suggests that, during flow, individuals "let go" or switch into "autopilot" and experience less conscious control.

Moreover, experienced musicians in a flow state didn't seem to rely on the DMN to generate ideas, since its activity was down. Instead, they used the networks they had formed throughout their lives while honing their craft — in other words, networks involved in hearing and playing guitar, the researchers concluded.

Meanwhile, less-experienced musicians showed little change in the baseline activity of their ECNs, DMNs, or other processing centers while improvising in either low- or high-flow states. This suggests that only through gaining expertise and "letting go" can a person hope to achieve a high state of flow.

According to van der Linden, these findings address key questions in neuroscience and are especially impactful because they looked at brain activity during a real-life creative task rather than one invented for a study.

"This can be the basis for new techniques for instructing people to produce creative ideas," Kuonios said in a statement. In future work, the group hopes to confirm their theory with other creative tasks, such as drawing, while replicating the findings with higher-resolution brain-scanning techniques.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Jennifer Zieba earned her PhD in human genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles. She is currently a project scientist in the orthopedic surgery department at UCLA where she works on identifying mutations and possible treatments for rare genetic musculoskeletal disorders. Jen enjoys teaching and communicating complex scientific concepts to a wide audience and is a freelance writer for multiple online publications.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus