Mosquito larvae launch their heads like tiny harpoons to nab prey, video reveals

Researchers have captured the first-ever footage of mosquito larvae flinging their heads at prey in deadly hunting strikes.

How do mosquito larvae catch their prey? By using their heads.

In attacks that are too swift to be seen with the naked eye, predatory aquatic larvae, which measure about 0.75 inch (2 centimeters) long, launch their heads toward their victims like tiny harpoons, high-speed film footage reveals.

In a decades-long investigation, scientists filmed larvae in three mosquito species as they consumed their prey. The findings, published Oct. 4 in the journal Annals of the Entomological Society of America, revealed that two of those species — Toxorhynchites amboinensis and Psorophora ciliata — could launch their heads to snap up a target meal in about 15 milliseconds. And in a surprise twist, the researchers discovered that speedy prey nabbing also happened in Sabethes cyaneus, a mosquito species in which the larvae are primarily passive filter feeders.

"They were using their siphons to snag prey larvae and pull them into their gaping mouthparts," said lead study author Robert Hancock, a professor in the Department of Biology at the Metropolitan State University of Denver. "That was one of these, 'I can't believe this; this is amazing' kind of moments."

Related: Mosquito 'tongue' neurons ignite like fireworks at taste of human blood

Hancock first observed this blink-and-you'll-miss-it hunting prowess decades ago during a medical entomology class he attended as a grad student under study co-author Woody Foster, who's now a professor emeritus in the Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology at The Ohio State University in Columbus. In that class, as T. amboinensis larvae responded to prey, students watched the larvae under a microscope — or at least they tried to.

"We all saw a blur; then we saw a captured larva being shoveled into the mouth of a predator. That's all we saw," Hancock told Live Science. The next step, which would take more than 20 years to realize, was finding out what the predators were doing and how they were doing it.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

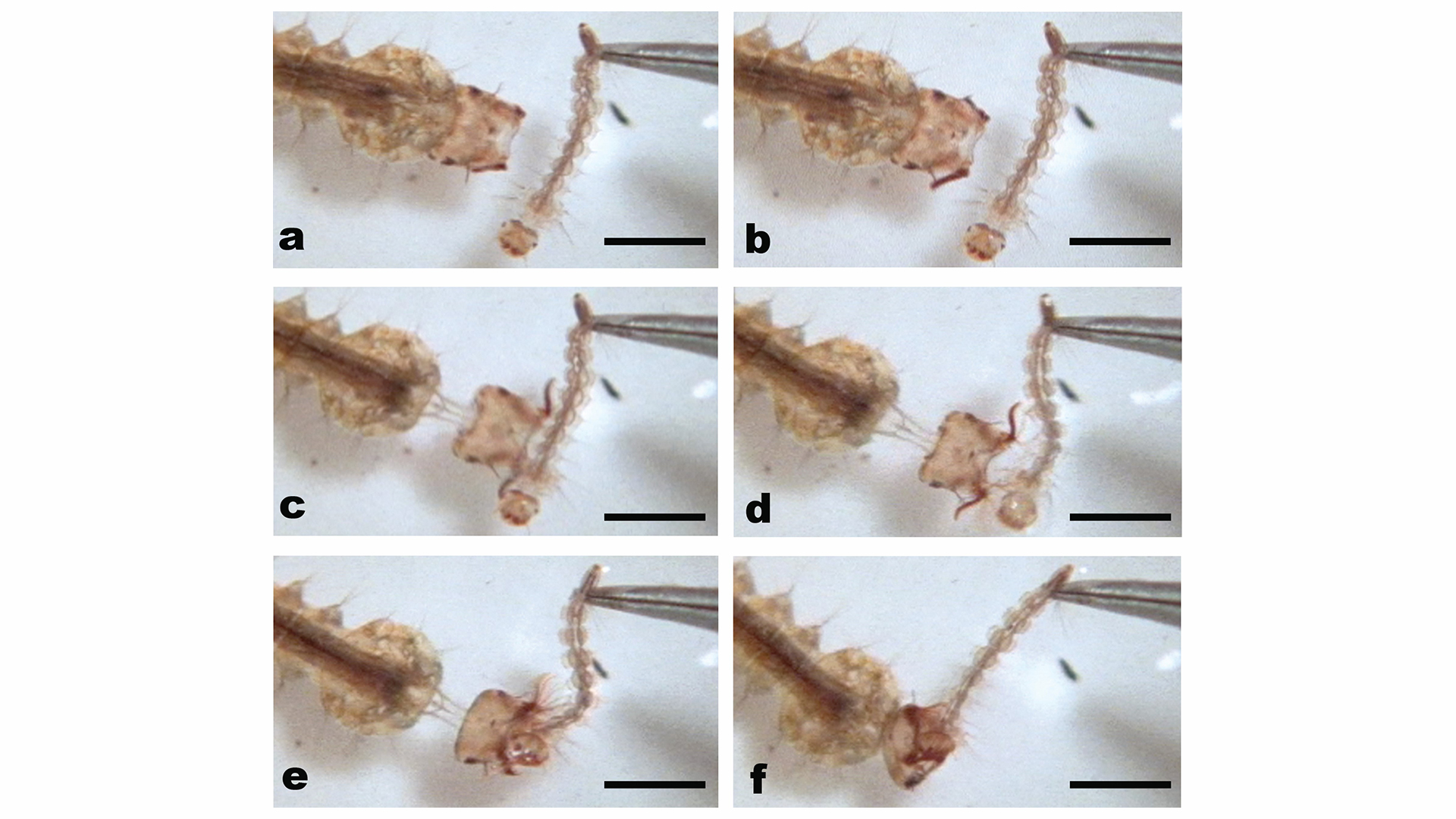

Hancock and his co-authors began filming experiments with T. amboinensis and P. ciliata in the 1990s, using the fastest-available optical system: a 16-millimeter film camera that had been designed for the U.S. military to track missiles. Once the study authors adapted the camera to film through a microscope, they held prey larvae with jeweler's tweezers to temp the predators, ultimately capturing footage of the larvae at 340 frames per second (fps).

Most of the time, "the predators would make a little body movement when the prey was introduced to their environment," which would signal to the researchers that it was time to hit the button on the film camera, Hancock said.

"Body arching and head twisting"

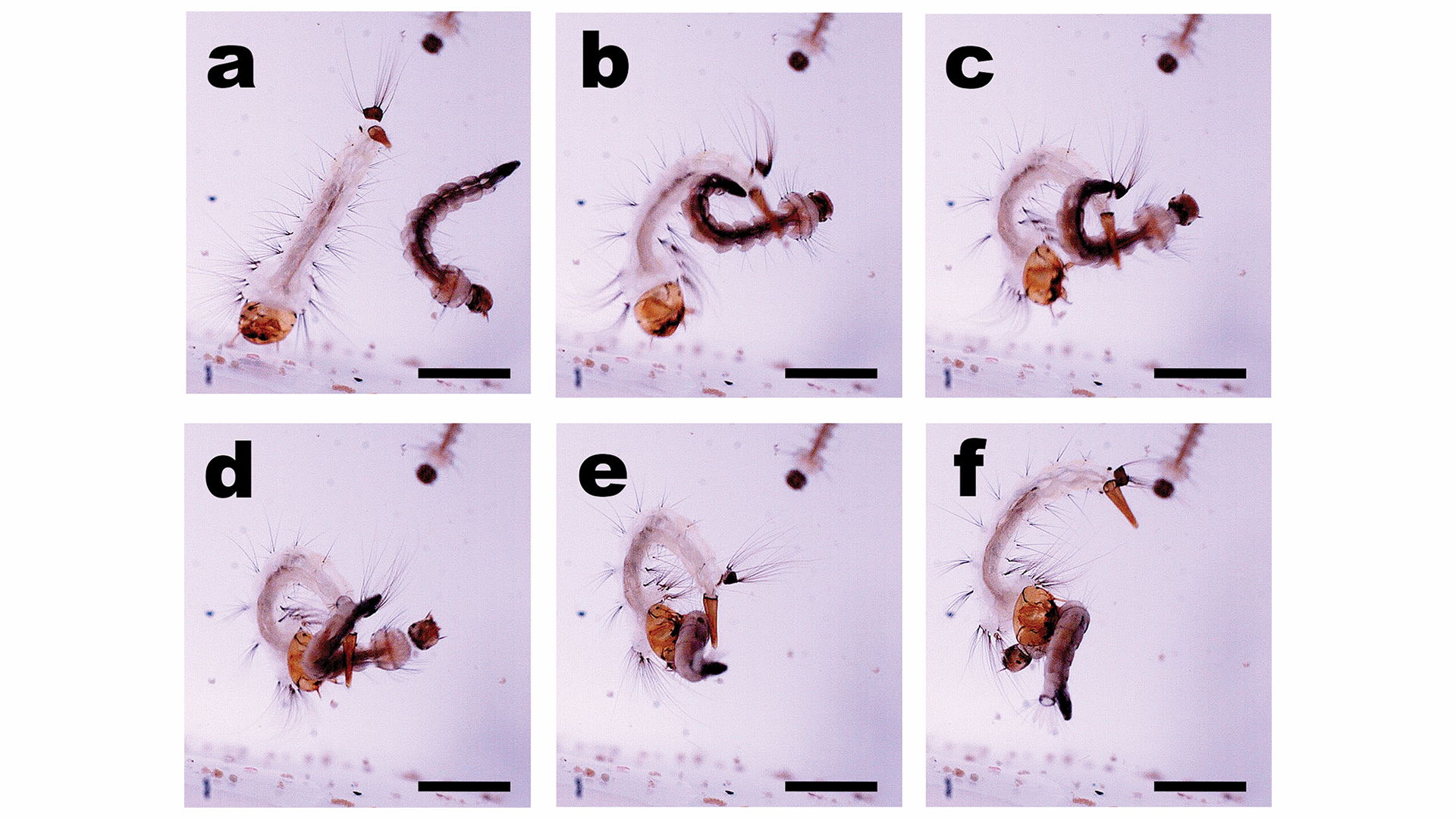

The scientists found that the larvae launched their heads using thrust from accumulated abdominal pressure, and bunches of tiny brushlike bristles around their heads spread like fans into "basket-like arrangements" that helped sweep prey toward the predators' gaping and sharp-toothed jaws, the study authors wrote. P. ciliata "typically struck in a straight-ahead (axial-linear) fashion," according to the study, while strikes by T. amboinensis "often involved a great deal of both body arching and head twisting."

"All scientists get excited about their discoveries, but this kind of science — these visual discoveries — are special," Hancock said.

But T. amboinensis and P. ciliata larvae are active predators, and the scientists wondered if similar methods might be used by species that combined hunting with filter feeding. After funding dried up, the project was put on hold until 2020, when the researchers were finally able to revisit that question. This time, they used a high-definition video camera capable of shooting up to 4,352 fps, with which they recorded S. cyaneus larvae in specially designed "arenas" of death.

The predatory action they saw, in which the larvae used their tails to swiftly sweep prey into their waiting mouths, was also previously unknown; like the head-launching strikes, hunting with tail sweeps took about 15 milliseconds from start to finish and was "spectacular," Hancock said. Once S. cyaneus gripped its victim, the larvae's mandibles "opened and closed so that their serrated teeth tore into the prey," according to the study.

Future studies could explore how common harpoon-headed hunting and tail sweeping are across the mosquito lineage, by "getting my cameras on as many different kinds of mosquitoes as possible," Hancock said. "There's a much bigger story to be told."

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.