A 'monster' star 2 million times brighter than the sun disappears without a trace

The star's mysterious disappearance could hint at a new type of stellar death.

In 2019, scientists witnessed a massive star 2.5 million times brighter than the sun disappear without a trace.

Now, in a new paper published today (June 30) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, a team of space detectives (see: astrophysicists) attempt to solve the case of the disappearing star by providing several possible explanations. Of these, one twist ending stands out: Perhaps, the researchers wrote, the massive star died and collapsed into a black hole without undergoing a supernova explosion first — a truly "unprecedented" act of stellar suicide.

"We may have detected one of the most massive stars of the local universe going gently into the night," Jose Groh, an astronomer at Trinity College Dublin and a co-author of a new paper on the star, said in a statement.

Related: The 12 strangest objects in the universe

"If true, this would be the first direct detection of such a monster star ending its life in this manner," study lead-author Andrew Allan, also of Trinity College, said in the statement.

The star in question, located about 75 million light-years away in the constellation Aquarius, was well studied between 2001 and 2011. The bloated orb was a superb example of a luminous blue variable (LBV) — a massive star approaching the end of its life and prone to unpredictable variations in brightness. Stars like this are rare, with only a handful confirmed in the universe so far. In 2019, Allan and colleagues hoped to use the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope to learn more about the distant LBV's mysterious evolution, only to discover that the star had seemingly completely vanished from its host galaxy.

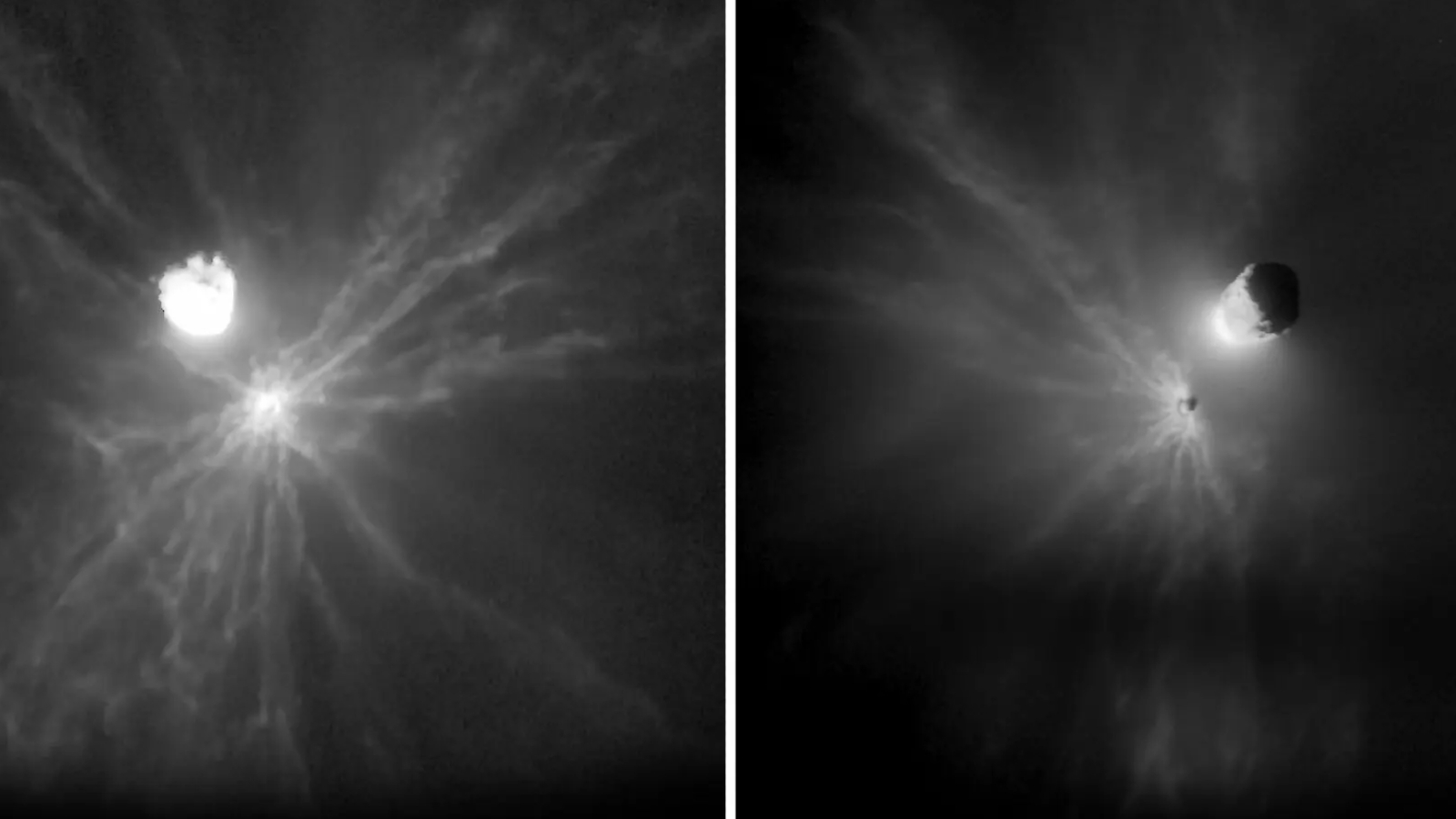

Normally, when a star much larger than our sun reaches the end of its life, it erupts in an enormous supernova explosion. These explosions are easy to spot, as they stain the sky around them with ionized gas and powerful radiation for many light-years in every direction. (Sometimes, this looks downright beautiful.) Following the blast, the dense core of leftover stellar material may collapse into a black hole or a neutron star — two of space's most massive and mysterious objects.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The missing LBV left no such radiation. It simply disappeared.

To investigate this mystery, the researchers looked back at previous observations of the star taken in 2002 and 2009. They discovered that the star had been undergoing a strong outburst period during this time, jettisoning enormous amounts of stellar material at a much faster rate than usual. LBVs can experience multiple outbursts like this in their temperamental old age, the researchers wrote, causing them to glow much more brightly than usual. The outburst likely ended sometime after 2011, the team said.

This could explain why the star appeared so bright during those early observations — still, it does not explain what happened after the outburst that caused the star to vanish. One explanation could be that the star dimmed considerably after its outburst, and was then further obscured by a thick veil of cosmic dust. If this were the case, then the star could reappear in future observations.

The weirder and more exciting explanation is that the star never recovered from its outburst, but instead collapsed into a black hole without going supernova. This would be a rare event, the team conceded. Given the star's estimated mass before its disappearance, it could have created a black hole measuring 85 to 120 times the mass of Earth's sun, though how this could have happened without a visible supernova is still an open question.

- The 15 weirdest galaxies in our universe

- The 12 strangest objects in the universe

- 9 Ideas about black holes that will blow your mind

Further observations of the distant, star-eating galaxy are required before this case can be officially closed.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.