The 5 craziest ways emperors gained the throne in ancient Rome

One gained it through money and another was found hiding behind a curtain.

For centuries, becoming emperor of the Roman Empire was an enticing prospect, and numerous people schemed, battled and murdered each other for this ultimate prize. But being the ruler of ancient Rome was a risky business, despite the immense wealth it brought and the almost unlimited authority over powerful armies and a vast territory. In 2019, a study in the journal Nature revealed that 62% — almost two-thirds — of Roman emperors died violently, which means their chances of surviving the early years of their reign and reaching a peaceful old age were worse than those of a Roman gladiator surviving a fight.

And merely gaining the imperial throne could be difficult, too. There was no established procedure for transferring power when a Roman emperor died, regardless of his cause of death, in spite of various attempts to establish the rules of succession. In total, there were about 77 emperors who led the Western Roman Empire, from Augustus in the first century B.C. to Romulus Augustus in the fifth century A.D. The Eastern Roman (or Byzantine) Empire had about 94 emperors between Constantine the Great in the fourth century and Constantine XI Palaeologus, who lost Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453. And almost every time an emperor died, the entire empire was thrown into chaos by the issue of who would assume power. Here's a list of some of the ways Roman emperors secured the coveted throne for themselves.

1. Inheritance

Inheriting a throne may seem straightforward in the modern world, where established royal families traditionally (and usually peacefully) pass on their titles to the next generation, but it wasn't so easy in the Roman Empire. "One of the weaknesses of the Roman imperial political system was that there were never any clear rules or principles for succession," Richard Saller, a professor of classics and history at Stanford University in California, told Live Science in an email. "That weakness goes back to the claim of the first emperor Augustus that he was restoring the [Roman] Republic in which public offices could not be inherited."

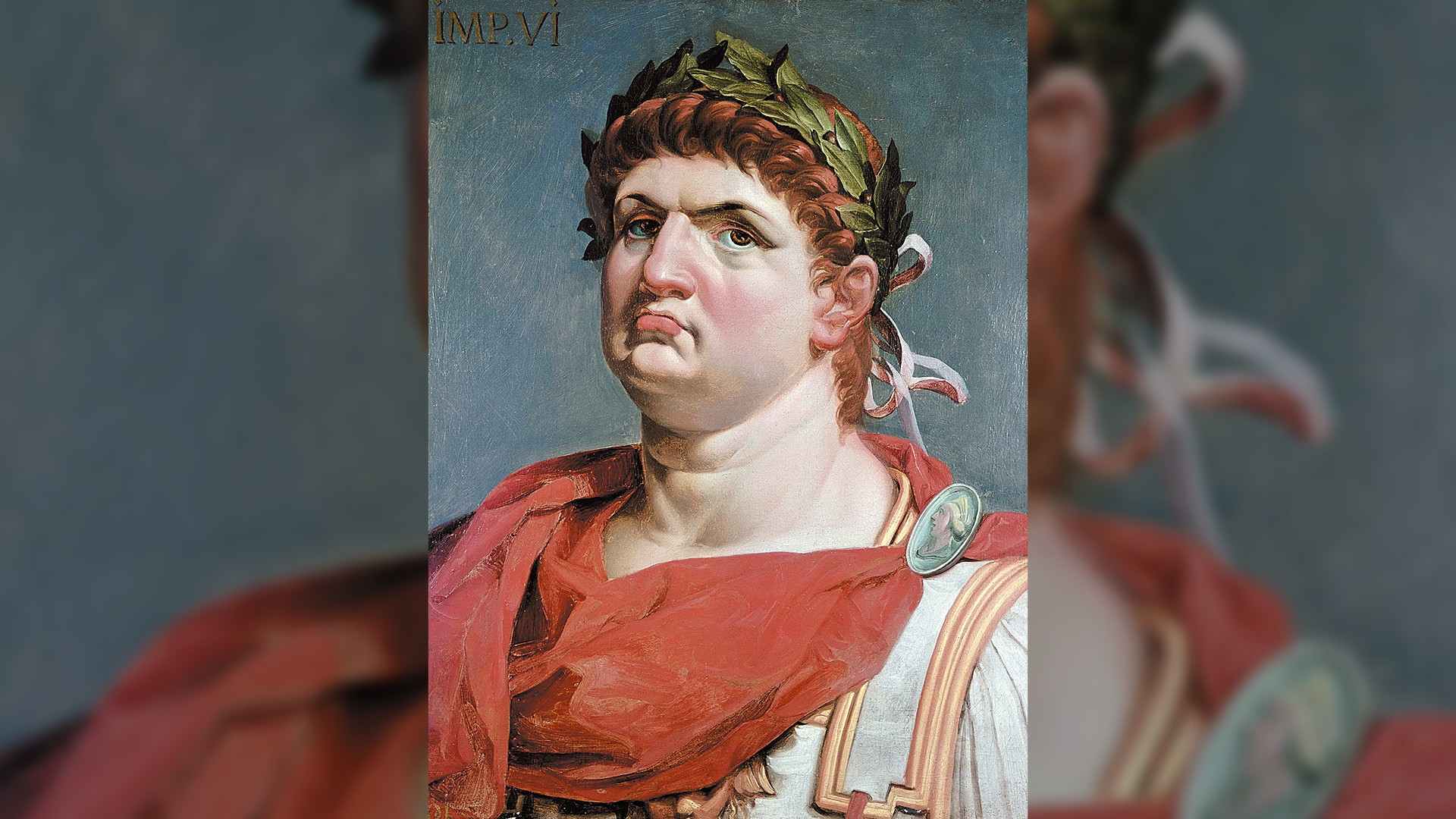

Probably the most famous emperor to inherit the throne was the fifth Roman emperor, Nero, who was born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus in A.D. 37. His mother, Julia Agrippina, a great-granddaughter of Augustus, became the fourth wife of the emperor Claudius in A.D. 49 and persuaded her new husband to adopt the boy later that year. Nero then inherited the imperial throne at age 17 after Claudius died in A.D. 54; several Roman historians alleged that Claudius had been poisoned by Agrippina in order to advance her son. But Nero showed no family loyalty, and after pretending to share power with his mother for several years he ordered Agrippina's murder in A.D. 59. According to the fist-century Roman historian Tacitus, Nero first tried poison, which didn't work; he then caused her boat to sink, which she swam away from; and finally, he ordered a straightforward assassination.

While Nero inherited the throne relatively peacefully, his reign ended in chaos: Beset by problems, Nero was declared a public enemy by the senate and abandoned by the army, and he committed suicide in A.D. 68. He had no living children to succeed him, and the empire plunged into violence as multiple claimants fought to secure the throne.

2. The Praetorian Guard

Claudius, the fourth Roman emperor, ascended the throne during an outbreak of violence that would echo for centuries. The Praetorian Guard originated during the Roman Republic as a corps of bodyguards for army generals, but the Praetorians were then appointed by Augustus, the first Roman emperor, in 27 B.C. to be the emperor's personal bodyguard. After that, they grew in prestige, and by the reign of the third emperor Caligula (real name Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus) they had become so powerful they could even topple an emperor.

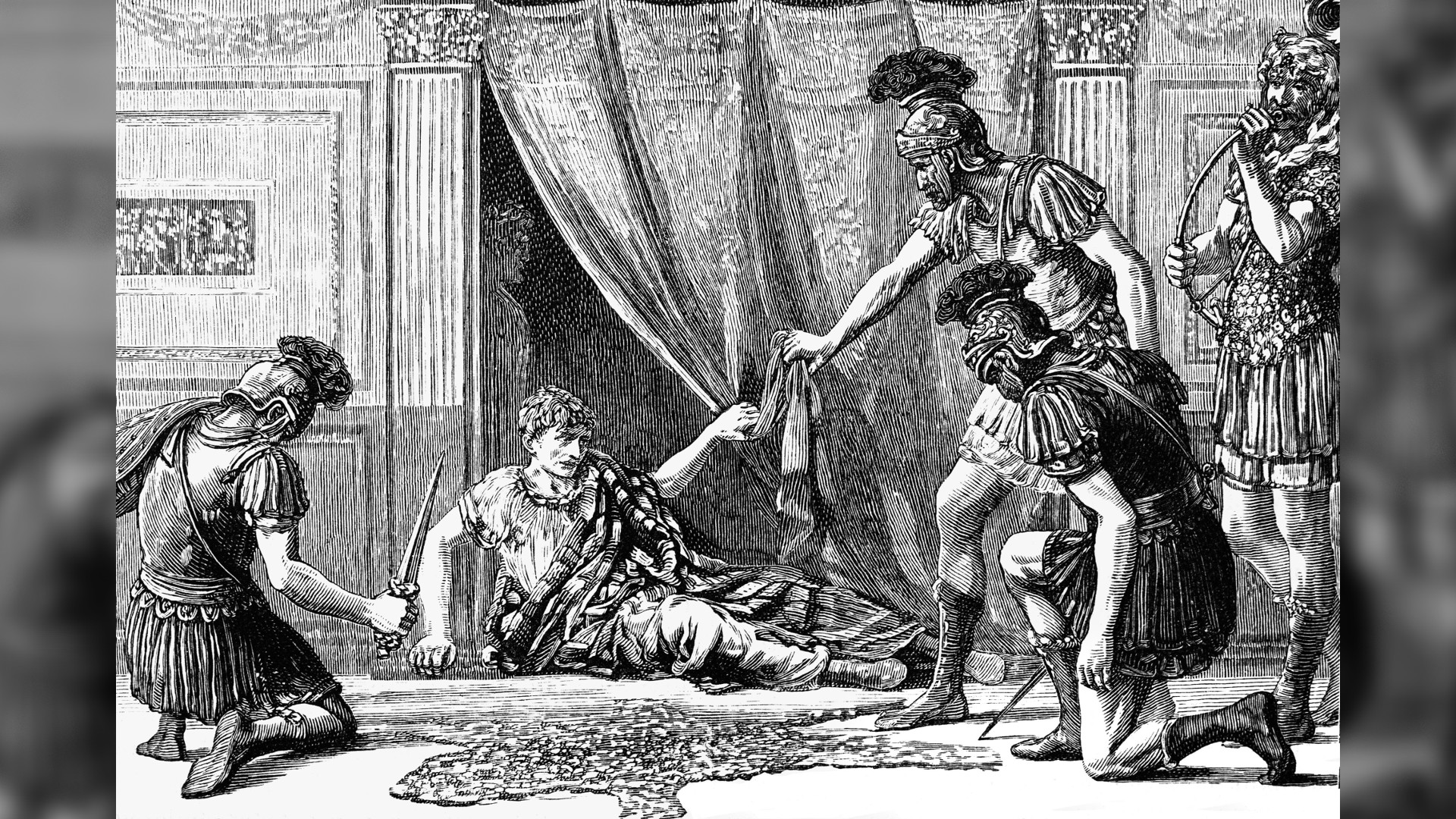

Caligula, a great-grandson of Augustus who reigned from A.D. 37, was initially popular, but stories of his predilections for sadism and sexual perversion have led him to be portrayed as a brutal and lascivious tyrant. Eventually he alienated both the Roman nobility and the army, and Caligula was assassinated by officers of the Praetorian Guard in A.D. 41.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Praetorian soldiers then rampaged through the imperial palace. According to the first-century Jewish and Roman historian Josephus, they found Claudius — Augustus' great nephew and Caligula's uncle — hiding behind a curtain. The Praetorians proclaimed Claudius emperor, and he ruled with their support until his death in A.D. 54. This was the first time the Praetorian Guard had selected a Roman emperor, but it would not be the last.

3. Buying it

After the emperor Commodus' assassination in A.D. 192 (instigated by the leader of the Praetorian Guard), the Roman Empire entered a period known as the "Year of the Five Emperors." Pertinax, who was a senior senator of Rome, was installed first; but the Praetorian Guard quickly became disappointed in him because he refused to pay them for their continued support. The Praetorians soon killed Pertinax, just three months after they proclaimed him emperor.

Didius Julianus was next on the throne. He'd served as governor of several provinces and was immensely wealthy. According to the second-century Roman historian Cassius Dio, the Praetorians announced after killing Pertinax that they would sell the throne to the man who paid the highest price, and Julianus won the subsequent bidding war by offering 25,000 sesterces to every Praetorian soldier — the equivalent of several years' pay. After accepting his offer, the Praetorians threatened the Roman senate until they proclaimed Julianus emperor.

But he didn't enjoy the throne for very long. The Roman people, who knew that he had purchased the emperorship, openly opposed the new emperor, and on one occasion pelted him with stones. Eventually, three different generals in the Roman provinces each declared themselves emperor, and they began advancing on Rome with their armies to enforce their claims. Julianus and the Praetorian Guard fought off one of the generals, Septimius Severus, and tried to negotiate a power-sharing deal with him; but eventually the Praetorians and the senate abandoned Julianus; they proclaimed Severus emperor and ordered Julianus to be executed, just 66 days after he'd ascended the throne.

4. Working up through the ranks

Several Roman emperors were born into very humble beginnings but worked their way up through the ranks of the Roman army to become officers and then commanders. Pertinax, for example, was the son of a freed slave, although he only lasted for a few months as emperor. Perhaps the most famous examples are Diocletian, who was born into a low-status family in Dalmatia before rising to become emperor in A.D. 284; and his co-emperor Maximian, the son of a Pannonian shopkeeper, who ruled until A.D. 305. Diocletian and Maximian had met during their ascents through the Roman army and were a powerful combination; the British classicist Timothy Barnes suggested in his 1982 book, "The new empire of Diocletian and Constantine," that Diocletian had the political brains while Maximian had the military brawn. Maximian first supported Diocletian to the imperial throne and then was appointed co-ruler a few years later. According to Britannica, Diocletian also introduced the office of "Caesar"— a junior emperor for each of the two senior emperors, who were titled "Augustus"— and the Roman Empire was ruled for a time by a "tetrarchy," or four rulers. Diocletian was emperor for around 20 years after assuming the throne, and then retired to his palace at Aspalathos (modern Split) in Dalmatia, dying in about 316. Maximian abdicated the throne at the same time that Diocletian retired, in 305; but according to Britannica he claimed the title of Augustus again in 307 to help his son Maxentius to become emperor. After abdicating again in 308 Maximian lived at the court of the emperor Constantine; but he killed himself in 310 after a revolt he’d led against Constantine failed.

Historian William Broadhead at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge noted in an email to Live Science that the Roman Empire was a military autocracy. "The emperor's legitimacy was based on his command of the very powerful Praetorian Guard at Rome and of the majority of the legions stationed in the provinces," he said. "Those two military institutions learned soon enough that they could play the role of kingmaker." Rising through the army's ranks to be in command of legions was a key way for prospective emperors to gain the army's loyalty.

5. Marriage or motherhood

Tradition decreed that the Roman emperor had to be a man, but several women wielded power behind the imperial throne even if they did not rule directly. "According to Tacitus's account, it was Livia, wife of Augustus and mother of Tiberius, who was thought by many to have determined the first transition of imperial power, by removing [murdering] all potential heirs who were close of Augustus, thereby paving the way for her own son," Broadhead said. Tiberius was Livia's son from her previous marriage, so he was not the obvious heir to the throne. But he became Rome's second emperor upon Augustus' death in A.D. 14, thanks to Livia's actions and marriage to Augustus.

Nero's mother, Julia Agrippina, seems to have manipulated the emperor Claudius into adopting her son, who became emperor after Claudius' death in A.D. 54; and for a while she was hailed as the empire's co-ruler, although eventually Nero had her killed. Many of the stories associated with imperial women may have been embellished or invented, Broadhead said, but "even discounting the more scandalous features of the stories, we can appreciate the importance of [their] position within the imperial household as a determining factor in who gained the throne."

The power of imperial women was most prominent during the later stages of the Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantine Empire, which was based in Constantinople, modern-day Istanbul, after A.D. 330. One of the most powerful was the empress Irene, who came from a politically prominent Greek family and became the wife of the Byzantine emperor Leo IV. But after his death in A.D. 780, she ruled until A.D. 790 as sole regent in the name of her son, the future Constantine VI. When he was old enough, Constantine tried ruling by himself. But the British historian John Bagnell Bury relates that he was so bad at it that Irene had him deposed and then blinded, to ensure he could never be emperor again. Irene then ruled in her own right as empress from A.D. 797 until she was deposed in A.D. 802 by her finance minister, who became the emperor Nikephoros I. Irene died in exile on the island of Lesbos the following year.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus