Nearly 900 years ago, astronomers spotted a strange, bright light in the sky. We finally know what caused it.

The origins of the ancient supernova of A.D. 1181 remained a mystery for 840 years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In the 12th century, Chinese and Japanese astronomers spotted a new light in the sky shining as brightly as Saturn. They identified it as a powerful stellar explosion known as a supernova and marked its approximate location in the sky — but its cause remained a mystery.

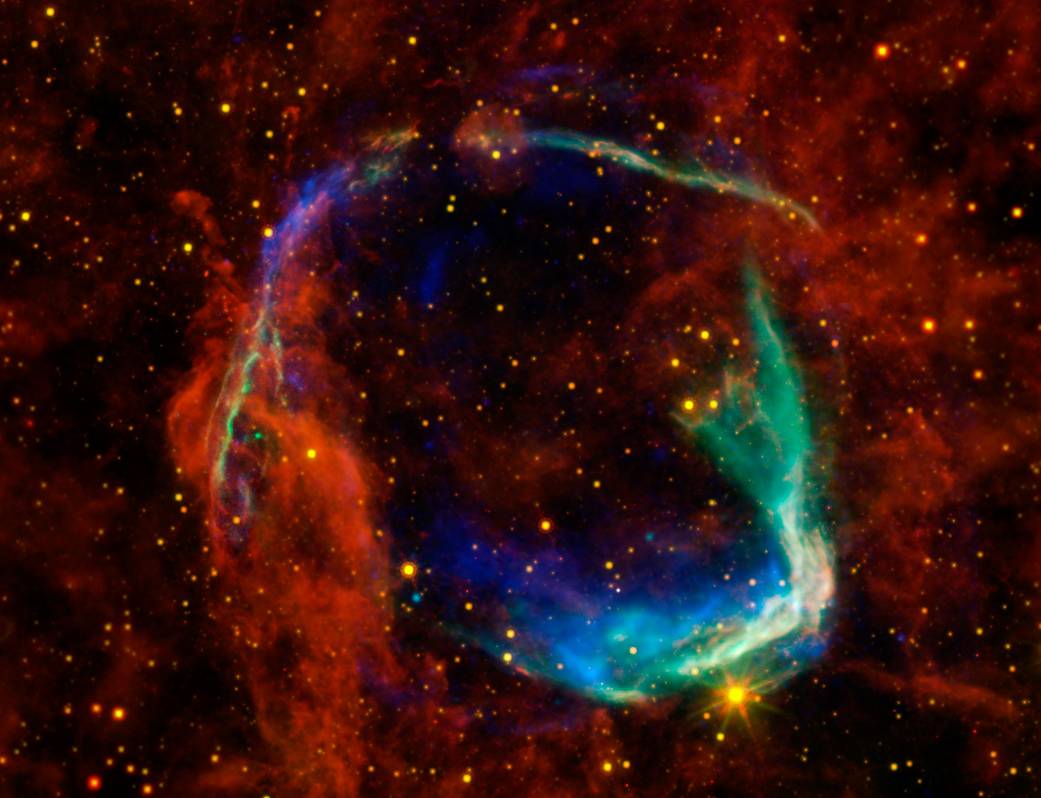

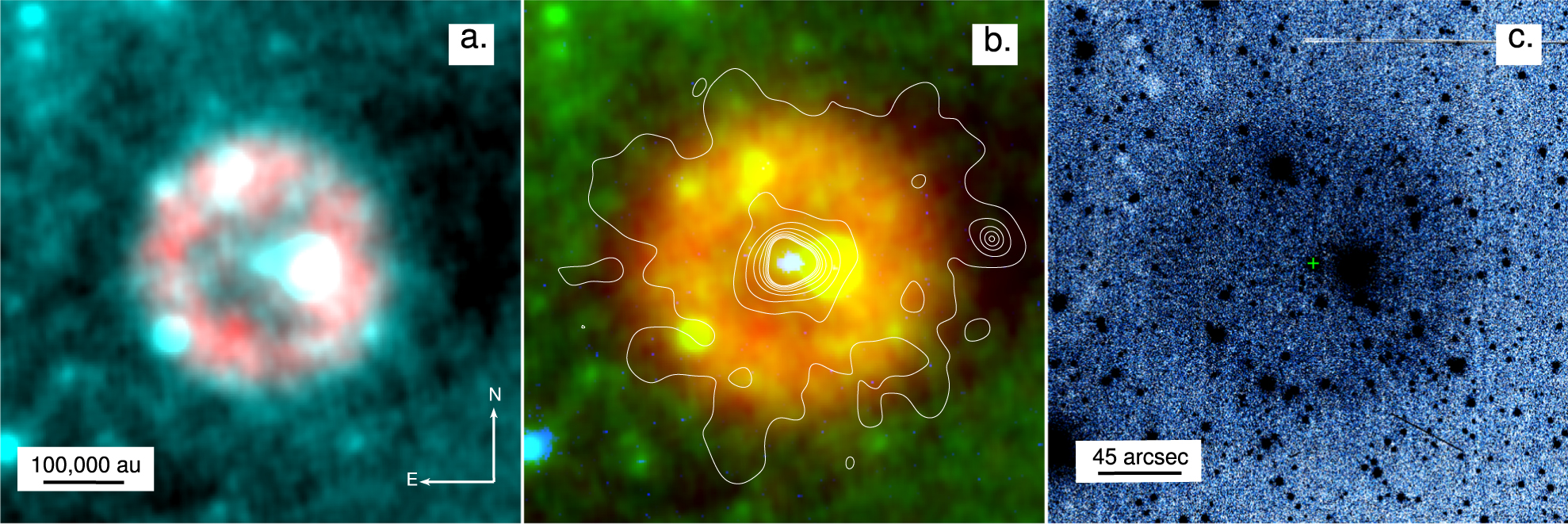

Now, astronomers say they have solved the 840-year-old puzzle: Two extremely dense stars collided in the Milky Way and caused a supernova. The explosion likely resulted in the formation of a sizzling-hot star, now known as Parker's star, and a nebula, an expanding shell of gas and dust, called Pa 30.

This supernova, or the so-called Chinese Guest Star, of A.D. 1181 — which remained visible from Aug. 6 to Feb. 6 of that year — is only one of nine historically recorded supernovas in our galaxy, according to the study, published Sept. 15 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Astronomers have identified the remnants of only a handful of these supernovas, but the Chinese Guest Star was the only supernova of the last millennium whose remnants were yet to be found.

Related: The 12 strangest objects in the universe

Some previous studies had suggested that another nebula, known as 3C 58, which is located near the marked location of the supernova, might be its remnants. But many factors, such as the age of the nebula, cast doubt on this theory. "Until now, there was no other viable candidate known for the remnant," the authors wrote in the study.

Astronomers discovered nebula Pa 30 in 2013. Then, in the new study, the researchers calculated how fast Pa 30 is expanding. They found that it was ballooning at a blistering 684 miles per second (1,100 kilometers per second). Knowing this rate, they calculated that the nebula must have been born around 1,000 years ago, which would place its origins around the time of this ancient supernova.

The researchers also had historical documents describing the star. "The historical reports place the Guest Star between two Chinese constellations, Chuanshe and Huagai. Parker's Star fits the position well," Albert Zijlstra, a professor of astrophysics at The University of Manchester in the U.K., said in a statement. "That means both the age and location fit with the events of 1181."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Previously, researchers had proposed that Pa 30 and Parker's star resulted from the merger of two white dwarfs, extremely dense stars that have used up all of their nuclear fuel, according to the statement. Such mergers lead to a relatively faint and rare type of supernova known as a Type lax supernova.

The A.D. 1181 supernova was faint and faded very slowly, suggesting it was likely a Type lax supernova, Zijlstra said in the statement. "Combining all this information — such as the age, location, event brightness and historically recorded 185-day duration" — suggests that Parker's star and Pa 30 are the remnants of this ancient supernova, Zijlstra said.

This is the only known Type lax supernova for which astronomers can conduct detailed studies on the remnant star and nebula, he added. "It is nice to be able to solve both a historical and an astronomical mystery," Zijlstra said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Editor's note: This article was updated to clarify that when the two super dense stars collided, it caused a supernova. The scientists say the nebula Pa 30, which was first discovered in 2013, is the remnant of the supernova.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus