Comb made from human skull may have been used in Iron Age rituals

A 2,000-year-old hair comb discovered in a museum's collection was carved from a human skull.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An ancient comb carved from a chunk of human skull has left researchers in London scratching their heads about whether or not it was actually used to style hair thousands of years ago.

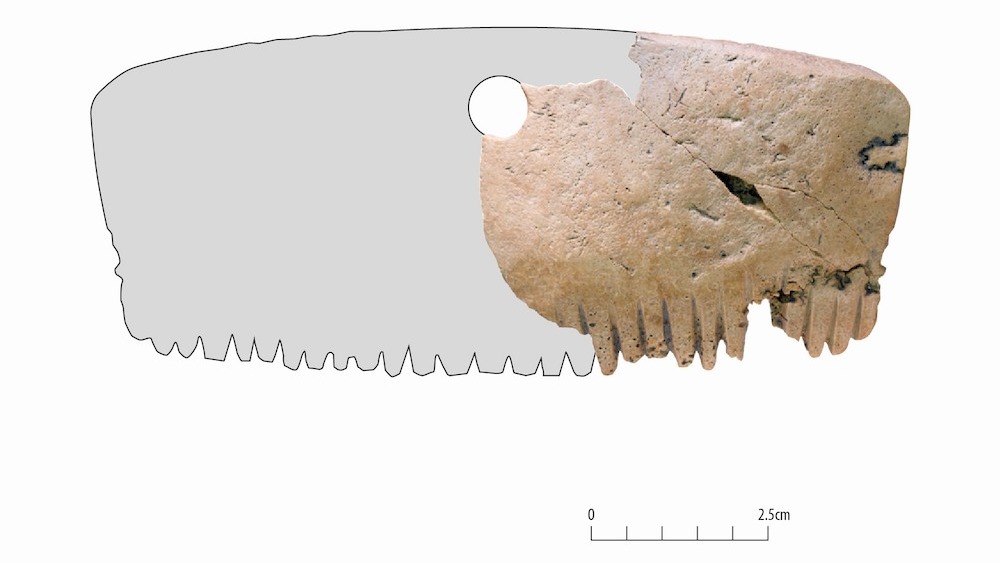

Archaeologists first discovered the item at Bar Hill, a village in Cambridgeshire, England, during a three-year dig that ended in 2018. The artifact, which dates to the Iron Age (750 B.C. to A.D. 43) and measures approximately 2 inches (5 centimeters) long, contains nearly a dozen carved teeth and was part of the collection at the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA).

Dubbed the Bar Hill Comb, the piece is one of 280,000 artifacts from the museum included in an ongoing analysis. Researchers can only theorize the true purpose of the item. There was no evidence showing wear on the comb's teeth, and a hole drilled into the top suggested it may have been worn as an amulet rather than used as a tool to style hair.

Despite its unknown purpose, the item offers a glimpse of how Iron Age people may have had different uses for human remains, the researchers said. These purposes may have included rituals.

Related: One of the oldest written sentences on record blasts hair and beard lice

"The Bar Hill Comb may have been a highly symbolic and powerful object for members of the local community," Michael Marshall, a prehistoric and Roman finds specialist at MOLA who led the project, said in a statement. "It is possible it was carved from the skull of an important member of Iron Age society, whose presence was in some way preserved and commemorated through their bones."

This isn't the first time an artifact reworked from human remains has been discovered in the region. Previous digs have revealed tools that were crafted from human leg and arm bones and used to clean animal skins, according to the statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Two similar pieces of repurposed human skull from Cambridgeshire also resemble combs. One, featuring carved teeth, was unearthed in the 1970s, and the other, with only incised lines, was found in the early 2000s. Marshall thinks that if the objects weren't intended for combing hair, the carvings were "meant to represent the natural sutures that join sections of the human skull," he said.

"It is possible this fascinating find represents a tradition carried out by Iron Age communities living solely in this area of Cambridgeshire," Marshall said. "To be able to see such hyper-local influences in groups of people living over 2,000 years ago is truly astonishing."

The Bar Hill Comb will join the Cambridgeshire Archaeology Archive, which houses artifacts unearthed across the region.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus