The most amazing coin treasures uncovered in 2021

Many of these hoards were found by amateur treasure-hunters

Saving for a rainy day is not a new idea. In 2021, archaeologists turned up a whole horde of hoards: stashes of coins and other valuables left behind for whatever reason and never used again. These treasures turned up in a Polish cornfield, in a meadow in New England, in a town in Denmark. They were left by royals, pirates, chieftains and people who will forever remain anonymous.

Many of these hoards were discovered by lucky amateurs with metal detectors or sharp eyes. Some date back as far as 1,500 years. From good luck pennies to the biggest Anglo Saxon hoard ever found, here were some of the year's most noticeable treasure troves.

Medieval gold coins and rings from a Polish cornfield

In 1935, the biggest hoard of coins from the Middle Ages ever found in Poland was unearthed in the village of Słuszków. In late 2020, a visitor returned to the town to learn more about that hoard, and they ended up finding another one.

Adam Kędzierski, an archaeologist at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology at the Polish Academy of Sciences, found the treasure trove of gold rings, silver ingots and silver coins after a tip from a local priest led him to a cornfield. There, he found a ceramic vessel full of buried treasure. The riches date back to 1105, and they may have belonged to Poland's first royal family. One of the gold rings is engraved "Lord, may you help your servant Maria," in Cyrillic, and might have been worn by Dobroniega Maria, a daughter of the Prince of Kiev, Vladimir the Great, Prince of Kiev, who was married to the Polish price Casimir the Restorer.

Read more: 6,500 medieval coins and rare gold rings unearthed in Polish cornfield

Roman-era silver coins in Turkey

Some 2,100 years ago, a high-ranking Roman soldier knelt by a stream in what is today Turkey and buried a cache of 651 silver coins.

No one knows who the soldier was or why he left the coins behind, but the hoard was in fantastic shape for its age, archaeologist Elif Özer told Live Science in February. The coins depict different scenes, with one showing a scene from the Aeneid in which Trojan hero Aeneas carries his family to safety out of a burning Troy. They also carry the images of multiple Roman emperors, including Julius Caesar.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Read more: Stash of more than 600 Roman-era silver coins discovered in Turkey

Bohemian grave of gold

"You can't take it with you" did not apply in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic) 1,600 years ago. In March, archaeologists described a fantastic find in a gravesite dating back to the fifth century: the remains of a middle-age woman who was buried surrounded by gold and precious gems.

There were several graves found in the area, but all had been looted except for one. In that grave, the archaeologists uncovered bones, glass beads and a golden headdress studded with semiprecious gems. Four buckles, also decorated with semiprecious stones, remained on the skeleton, left over from the clothes or wrappings that the woman took to her grave.

Read more: Gold and precious gems unearthed in a 5th-century grave in Bohemia

Loot from the crime of a century

A handful of silver coins found in New England may have been brought there by one of the most famous pirates in history.

The Arabian silver coins were found on Aquidneck Island, south of Providence, Massachusetts. Their age – they date to the late 1600s – and origin far from North America suggest they may have been spent by the pirate Henry Every and his crew. These notorious swashbucklers plundered the Mughal treasure ship Ganj-i-sawai in 1695 and made off with coins and riches worth millions. His band of marauders then fled to the New World. Every's fate is a bit of a mystery; he may have fled to Ireland and died there several years later, his share of the Ganj-i-sawai loot still unaccounted for.

Read more: Silver coins unearthed in New England may be loot from one of the 'greatest crimes in history'

Gold coins from the Black Death

Two bent and scuffed gold coins found in Norfolk County, England, were issued by King Edward III during a time when Black Death was ravaging the country.

The coins, found by a metal detectorist, were part of an effort to reintroduce gold coins to England after centuries of using silver. One, known as a "leopard," is 96% pure gold and was part of a run of coins issued only between January and July 1344, making it a rare find indeed. Leopards failed as coinage because they were too costly to produce and were overvalued compared with silver, according to England's Portable Antiquities Scheme. Whoever owned the coins was a wealthy individual, though: Together, the gold pieces were equivalent to $16,700 (12,000 British pounds) in today's money.

Read more: Metal detectorist unearths rare gold coins from Black Death period

Roman offering for safe passage

More than 100 Roman-era coins found by a river in the Netherlands were likely offerings for a safe passage across a ford, archaeologists revealed in July.

Amateur treasure-hunters discovered the 107 coins, many festooned with military imagery, by the Aa River near the town of Berlicum in 2017. No one knew why the coins were there until this year, when historian Liesbeth Claes, an assistant professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands, took a hard look at the clues: The coins were scattered over a large area and were minted over a period of 200 years, suggesting they were dropped one-by-one rather than buried as a hoard. They were also small denominations, mostly bronze with just a few pieces of silver. Finally, Claes and her colleagues found an old document mentioning that the spot where the coins had been found had once been a ford. Everything clicked. The coins had likely been dropped as a good-luck gesture by travelers, who dropped them in hopes of making it safely across the river, much as someone today might toss a penny into a wishing well.

Read more: 100 Roman coins were likely an offering for safe passage across river

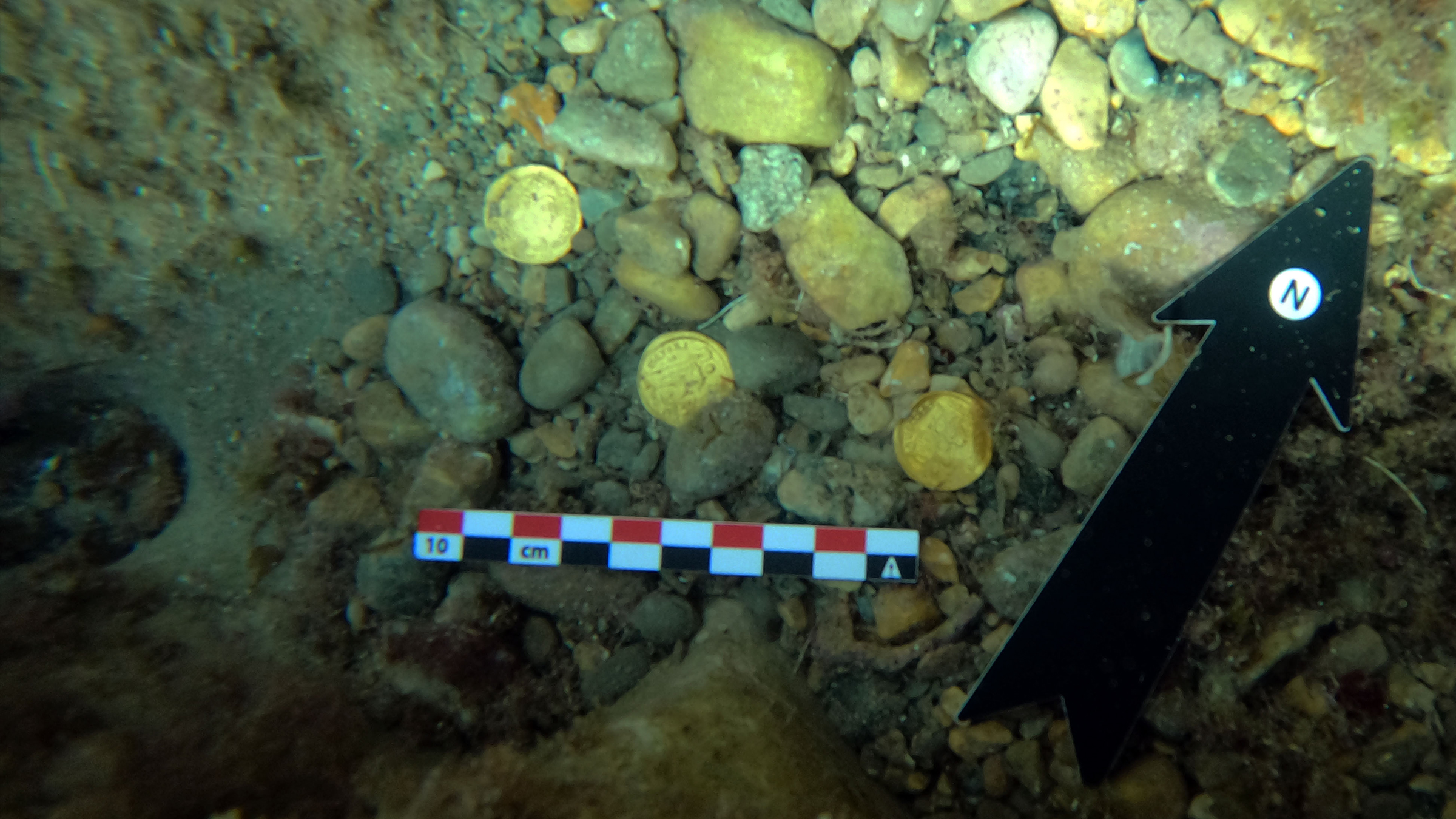

Gold treasure found by freedivers

A couple of vacationers picked up more than souvenirs from the bottom of Portitxol Bay, Spain, in August. The brothers-in-law, Luis Lens Pardo and César Gimeno Alcalá, were free-diving with rented snorkels when they spotted a glimmer of gold on the ocean floor.

The glimmer turned out to be 1,500-year-old gold coins, 53 of them, which the divers reported to the authorities. The coins dated to the latter days of the Western Roman Empire, between A.D. 364 and 408, and sported the faces of several emperors: Valentinian I, Valentinian II, Theodosius I, Arcadius and Honorius. There was no shipwreck nearby, but remnants of iron and wood nearby suggested the coins may have originally been buried within a small chest.

Read more: Amateur freedivers find gold treasure dating to the fall of the Roman Empire

Iron Age chieftain's hoard

Newly-minted metal detectorist Ole Ginnerup Schytz was surveying a friend's land in Vindelev, Denmark, with his new metal detector when he experienced the epitome of beginner's luck: He turned up a hoard of coins, jewelry and ornaments dating back to the Iron Age.

The stash contained 2.2 pounds (1 kilogram) of gold. The discovery kicked off a full archaeological excavation, which revealed remnants of a longhouse around the hoard, suggesting that the spot was the site of a powerful village during the sixth century, when the gold was buried.

Among the treasures were Roman coins melted into jewelry and several gold discs called bracteates, one of which may depict the Norse god Odin.

Read more: Treasure hunter finds gold hoard buried by Iron Age chieftain

The largest Anglo-Saxon hoard ever

A metal detectorist in West Norfolk, England, turned up the largest hoard of Anglo-Saxon coins ever found in the country — a discovery that ultimately triggered a crime.

The anonymous treasure-hunter turned up 131 coins and four golden objects over the course of six years. That person reported the coins to the authorities, as is required in England in cases where the find might be more than 300 years old and made up of at least 10% precious metal. But another metal detectorist, police officer David Cockle, dug up 10 of the coins and illegally sold them. Cockle was sentenced to 16 months in prison, and two of the 10 coins he sold have not been recovered.

Black-market dealings aside, the coins remain a spectacular find, according to the British Museum. They were buried around A.D. 600, at a time when what is today England was made up of several independent Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The hoard is the largest ever found from this era, topping the 101-piece Crondall hoard discovered in 1828.

Read more: Metal detectorist unearths largest Anglo-Saxon treasure hoard ever discovered in England

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.