2,000-year-old Celtic hoard of gold 'rainbow cups' discovered in Germany

The ancient hoard's "value must have been immense."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A volunteer archaeologist has discovered an ancient stash of Celtic coins, whose "value must have been immense," in Brandenburg, a state in northeastern Germany.

The 41 gold coins were minted more than 2,000 years ago, and are the first known Celtic gold treasure in Brandenburg, Manja Schüle, the Minister of Culture in Brandenburg announced in December 2021.

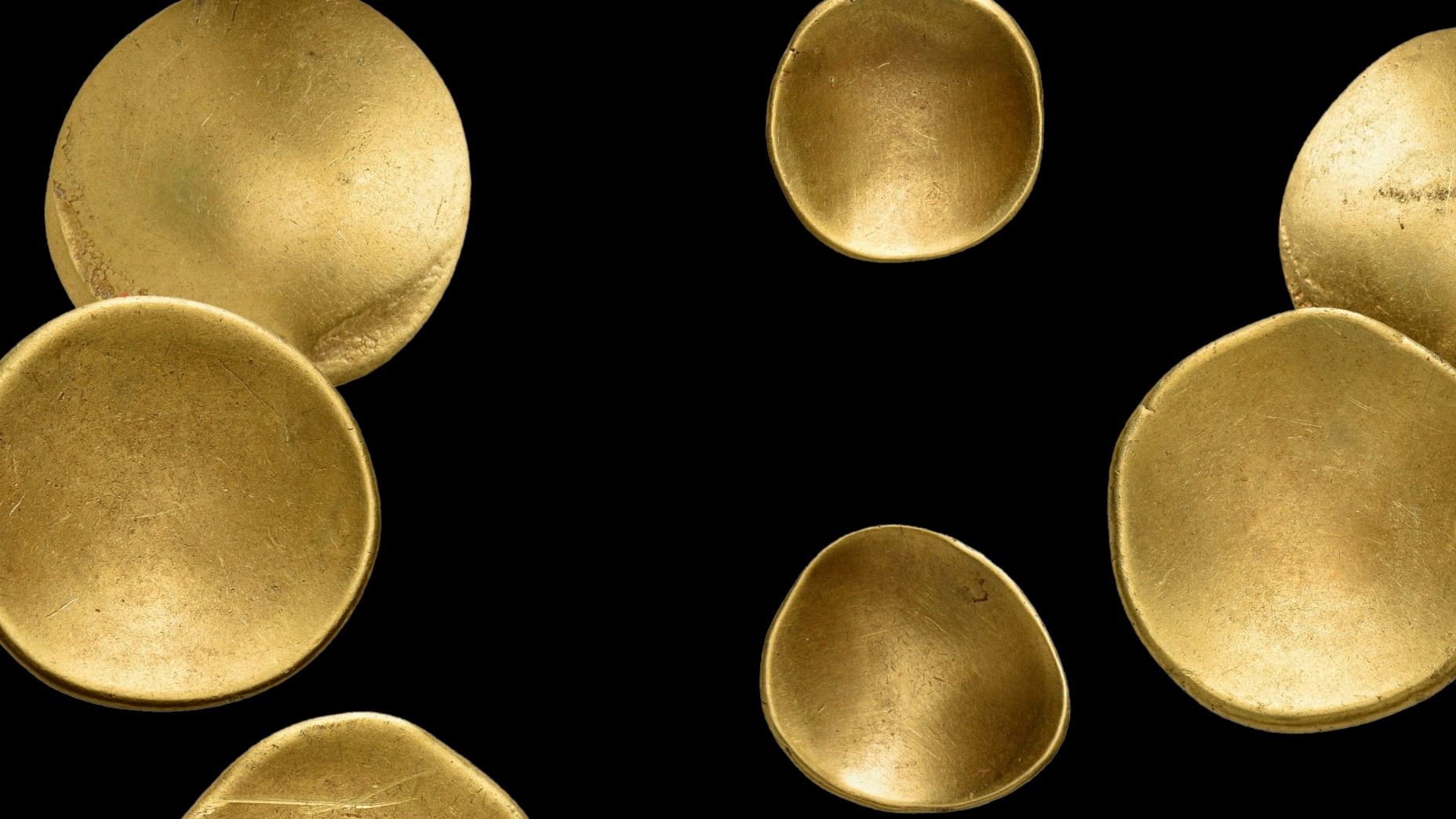

The coins are curved, a feature that inspired the German name "regenbogenschüsselchen," which translates to "rainbow cups." Just like the legend that there's a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow, "in popular belief, rainbow cups were found where a rainbow touched the Earth," Marjanko Pilekić, a numismatist and research assistant at the Coin Cabinet of the Schloss Friedenstein Gotha Foundation in Germany, who studied the hoard, told Live Science in an email.

Another piece of lore is that rainbow cups "fell directly from the sky and were considered lucky charms and objects with a healing effect," Pilekić added. It's likely that peasants often found the ancient gold coins on their fields after rainfall, "freed from dirt and shining," he said.

Related: Treasure hunter finds gold hoard buried by Iron Age chieftain

The hoard was discovered by Wolfgang Herkt, a volunteer archaeologist with the Brandenburg State Heritage Management and Archaeological State Museum (BLDAM), near the village of Baitz in 2017. After Herkt got a landowner's permission to search a local farm, he noticed something gold and shiny. "It reminded him of a lid of a small liquor bottle," Pilekić said. "However, it was a Celtic gold coin."

After finding 10 more coins, Herkt reported the discovery to the BLDAM, whose archaeologists brought the hoard's total to 41 coins. "This is an exceptional find that you probably only make once in a lifetime," Herkt said in a statement. "It's a good feeling to be able to contribute to the research of the country's history with such a find."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By comparing the weight and size of the coins with those of other ancient rainbow cups, Pilekić was able to date the hoard's minting to between 125 B.C. and 30 B.C., during the late Iron Age. At that time, the core areas of the Celtic archaeological culture of La Tène (about 450 B.C. to the Roman conquest in the first century B.C.) occupied the regions of what is now England, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Austria, southern Germany and the Czech Republic, Pilekić said. In southern Germany, "we find large numbers of rainbow cups of this kind," he noted.

However, Celts did not live in Brandenburg, so the discovery suggests that Iron Age Europe had extensive trade networks.

What was in the hoard?

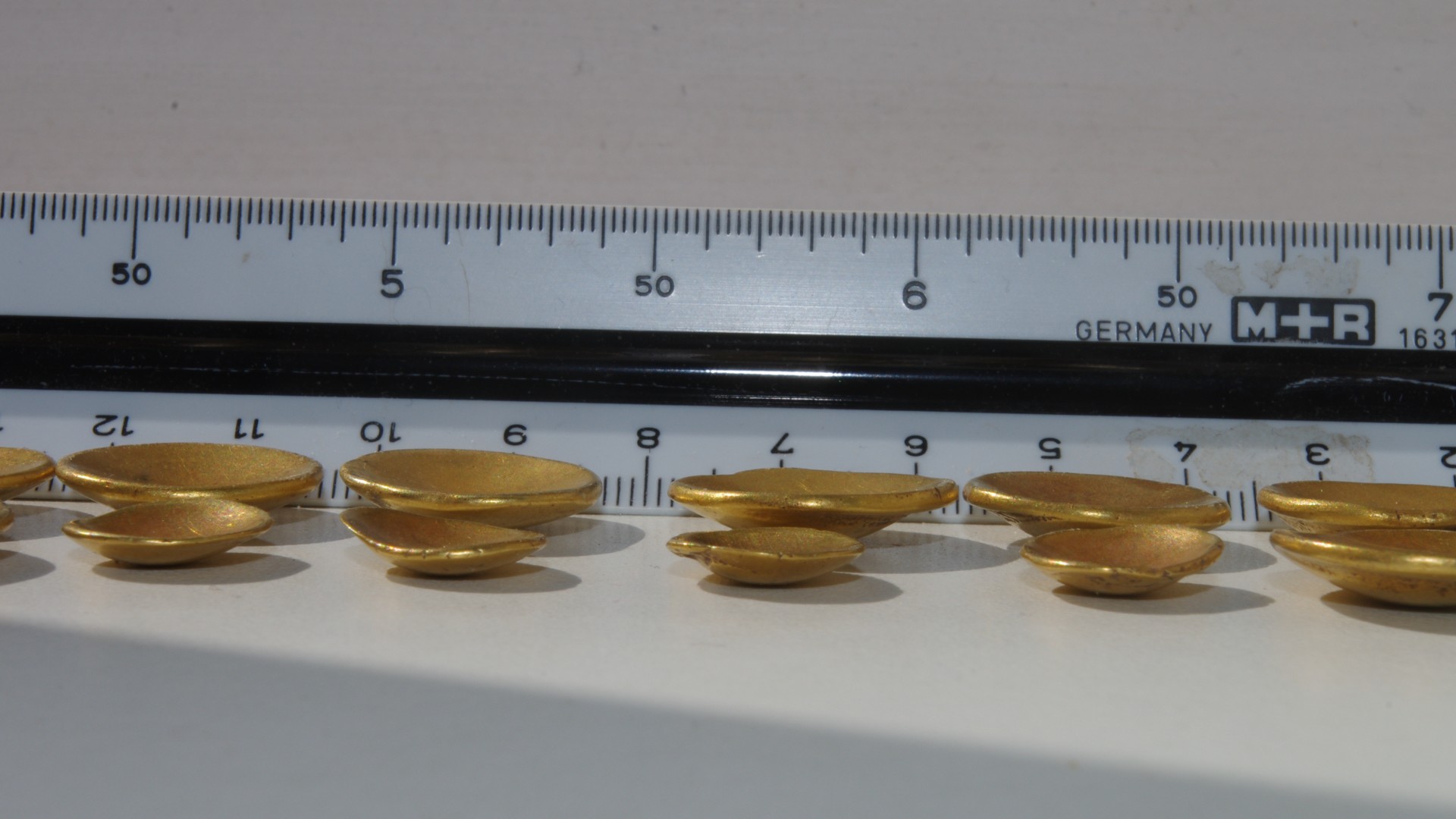

Of the 41 gold coins, 19 are coins known as staters, which have a diameter of 0.7 inches (2 centimeters) and an average weight of 0.2 ounces (7.3 grams), and 22 are 1/4 staters, which have a smaller diameter of 0.5 inches (1.4 cm) and an average weight of 0.06 ounces (1.8 g). The entire stash is imageless, meaning they are "plain rainbow cups," said Pilekić, who is also a doctoral candidate of archaeology of coinage, money and the economy in Antiquity at Goethe University, Frankfurt.

Because the coins in the stash are similar, it's likely that the hoard was deposited all at once, he said. However, it's a mystery why this collection — the second largest hoard of "plain" rainbow cups of this type ever found — ended up in Brandenburg.

"It is rare to find gold in Brandenburg, but no one would have expected it to be 'Celtic' gold of all things," Pilekić said. "This find extends the distribution area of these coin types once again, and we will try to find out what this might tell us that we did not yet know or thought we knew."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus