Black hole 'spaghettified' a star into a doughnut shape, and astronomers captured the gory encounter

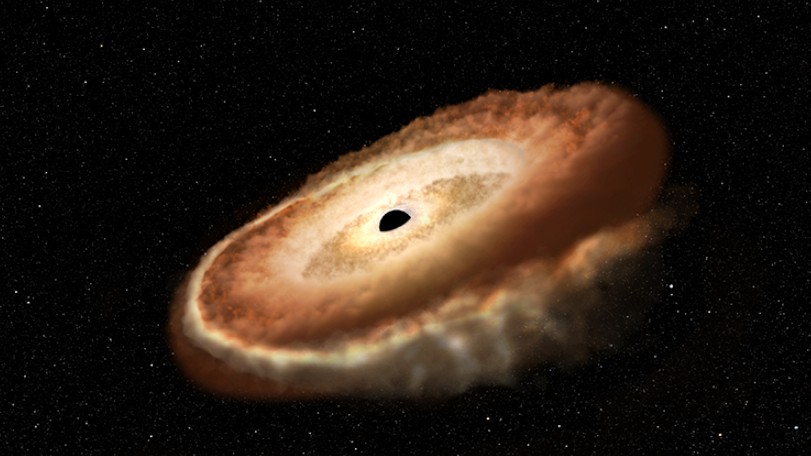

The black hole wrapped the layers of the shredded star around itself to form the perfect doughnut of doom.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The Hubble Space Telescope has spotted a star being stripped and stretched into a doughnut shape as a black hole devours it.

The supermassive black hole, located 300 million light-years from Earth at the core of the galaxy ESO 583-G004, snared and shredded the star after it wandered too close, sending out a powerful beam of ultraviolet light that astronomers used to locate the violent encounter.

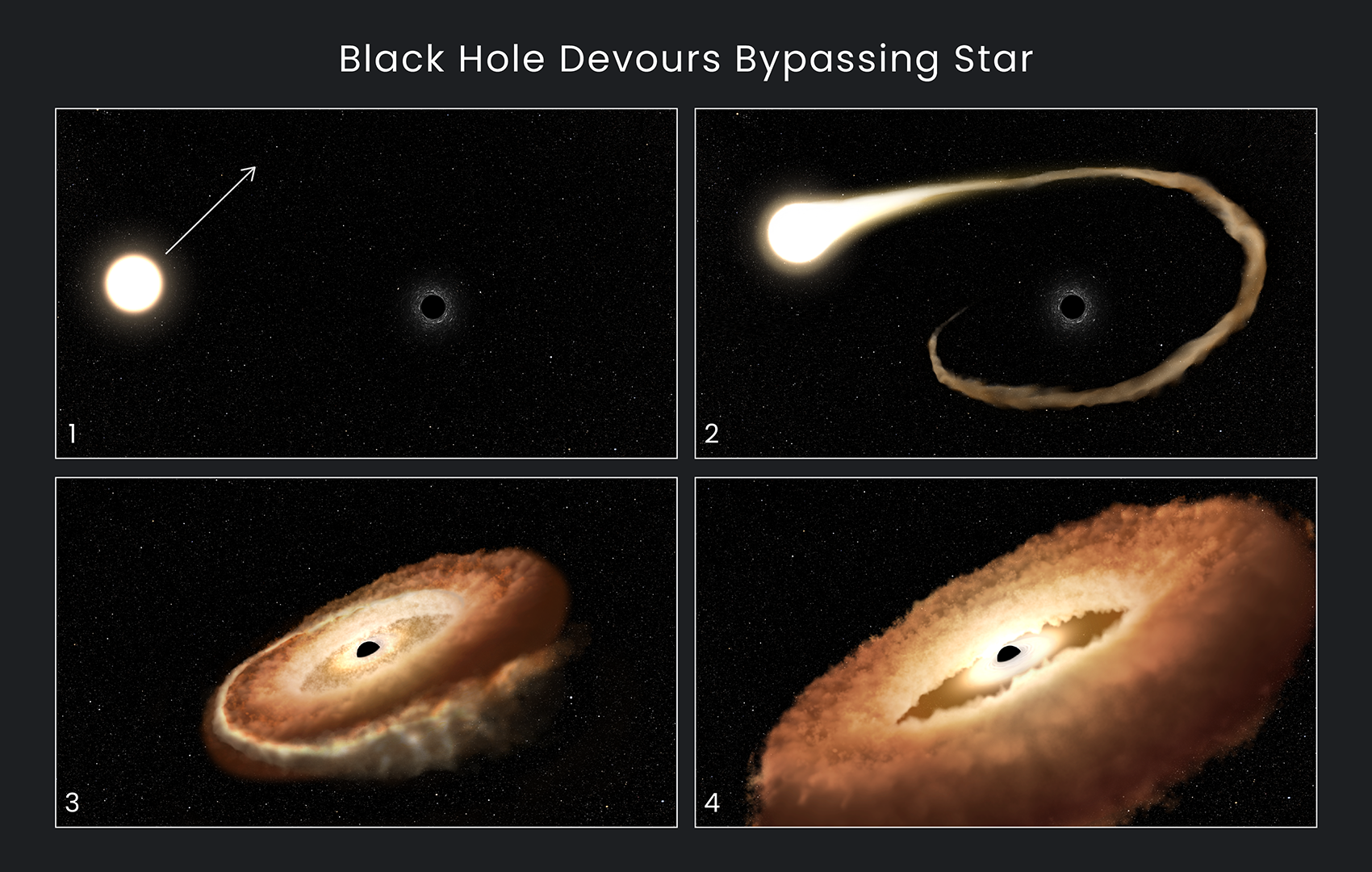

When a black hole feeds, its immense gravity exerts powerful tidal forces on the unfortunate star. As the star is reeled ever closer to the black hole's maw, the gravity affecting the regions of the star closer to the black hole is far stronger than that acting on the star's farside. This disparity "spaghettifies" the star into a long, noodle-like string that gets tightly wound around the black hole layer by layer — like spaghetti around a fork.

This doughnut of hot plasma quickly accelerates around the black hole and spins out into an enormous jet of energy and matter, which produces a distinctive bright flash that optical, X-ray and radio-wave telescopes can detect.

The exceptional brightness of this particular black hole feeding session allowed astronomers to study it over a longer time period than is typical for tidal disruption events. This could yield exciting new insights about the unfortunate star’s final moments, the researchers said.

Related: Wormhole simulated in quantum computer could bolster theory that the universe is a hologram

"We're looking somewhere on the edge of that donut," Peter Maksym, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in a NASA statement. "We're seeing a stellar wind from the black hole sweeping over the surface that's being projected towards us at speeds of 20 million miles per hour (three percent the speed of light). We really are still getting our heads around the event."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For a star, spaghettification is a dramatic process. The outer atmospheric layers of the star are stripped first. Then, they circle the black hole to form the tight yarn ball the researchers observed. The remainder of the star soon follows, accelerating around the black hole. Despite black holes' reputation as voracious eaters, most of the star's matter will escape; only 1% of a typical star ever gets swallowed by a black hole, Live Science previously reported.

The results were reported at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society, held in Seattle this week.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus