Roman-era 'fast food' discovered in ancient trash heap on Mallorca

Songbird bones found in a Roman-era trash pit on Mallorca suggests they were a tasty tweet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

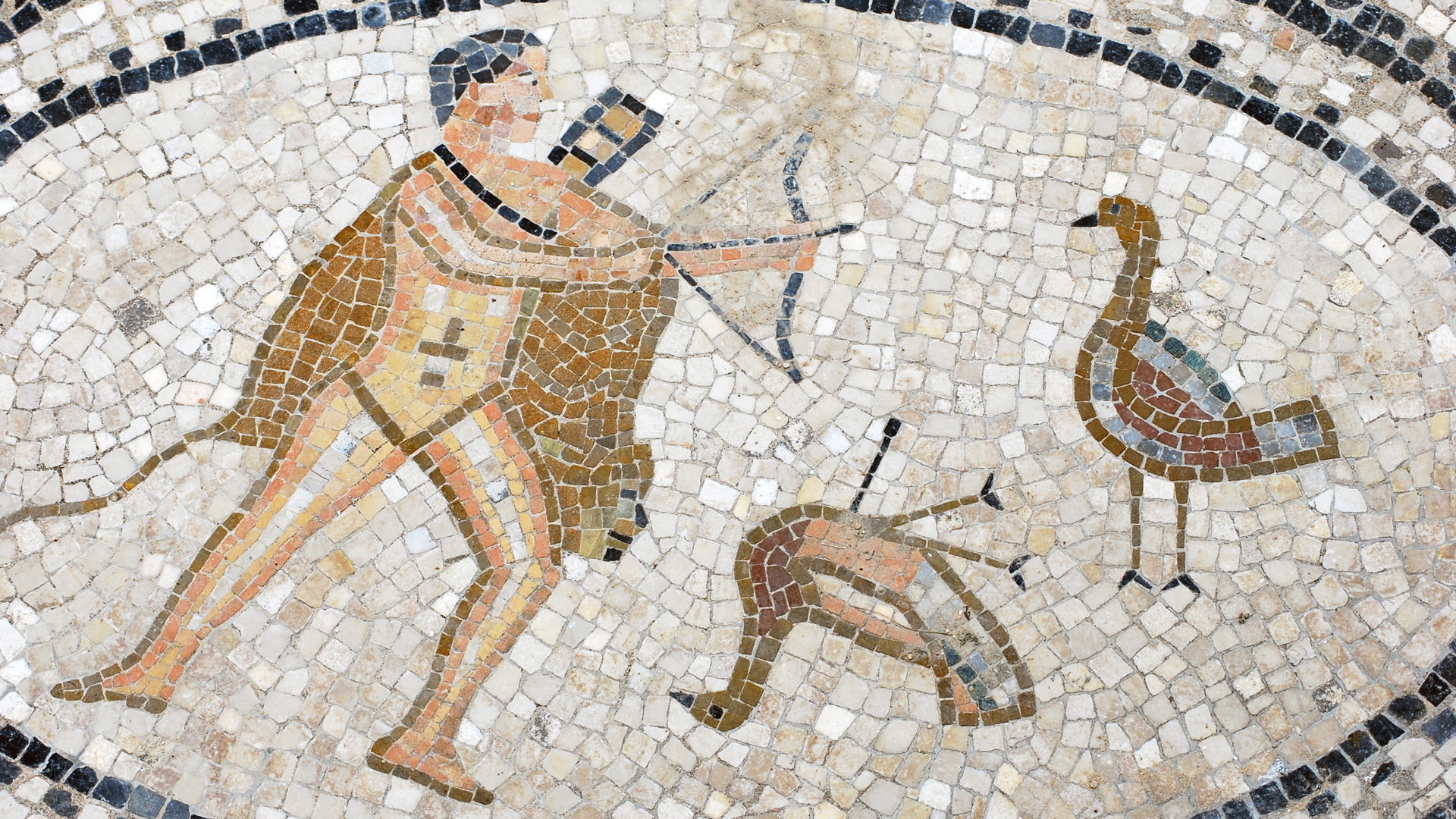

Songbirds were on the menu 2,000 years ago on the Roman island of Mallorca, archaeological evidence reveals. Bones of the small thrushes were discovered in a trash pit near the ancient ruins of a fast-food shop, giving researchers new clues about Roman-era street food.

"Based on local culinary traditions here in Mallorca — where song thrushes (Turdus philomelos) are still occasionally consumed — I can say from personal experience that their flavor is more akin to small game birds like quail than to chicken," Alejandro Valenzuela, a researcher at the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Studies in Mallorca, Spain, told Live Science in an email.

In a new study published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Valenzuela detailed his analysis of a collection of animal bones discovered in the ancient city of Pollentia , which was established after the Romans conquered the Balearic Islands in 123 B.C. Pollentia quickly became an active Roman port, and the city expanded to include a forum, temples, cemeteries and a network of shops.

One of these shops likely functioned as a "popina" — a small establishment where locals could gather and grab a snack or some wine — as archaeologists found six large amphorae embedded in a countertop. Nearby, a roughly 13-foot-deep (4 meters) cesspit had been filled with garbage, including broken ceramics that helped date the pit's use to between 10 B.C. and A.D. 30, along with a variety of mammal, fish and bird bones.

But Valenzuela was interested in investigating the role of small birds in the ancient Mallorcan diet, since their fragile bones are often poorly preserved at archaeological sites. In the Pollentia pit, though, there were more bones from song thrushes than from any other kind of bird.

By looking closely at the specific thrush bones found in the cesspit, Valenzuela found a pattern: While there were numerous skulls and breastbones (sterna) from the small birds, there were almost no arm and leg bones or bones of the upper chest, which are associated with the meatiest parts of the bird.

Related: Mass grave of Roman-era soldiers discovered beneath soccer field in Vienna

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The absence of the fleshy portions of the bird carcasses "suggests that thrushes were widely consumed, forming part of the everyday diet and urban food economy" at Pollentia, Valenzuela wrote in the study.

Historical records show that Roman game hunters often caught song birds in large groups using nets or pit traps, and then sold them to retail establishments that cooked and distributed them as food.

Based on the bone evidence, Valenzuela thinks the birds were prepared by removing the sternum to flatten the breasts. This technique would have allowed the food vendor to rapidly cook the bird — either on a grill or pan-fried in oil — while retaining moisture.

The broken ceramics found in the cesspit could suggest that the thrushes were served on plates just as they would have been in a home dining context. "However, given their small size and the street food context, it's also entirely plausible that they were presented on skewers or sticks for easier handling — both options are possible," Valenzuela said.

Along with thrush bones, Valenzuela found that the Romans ate domestic chickens (Gallus gallus) and European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in large quantities, suggesting they were also on the menu at this ancient fast-food joint.

Roman cities had a dynamic approach to food, Valenzuela wrote in the study, as seasonal products like thrushes were easily integrated into everyday diets, and "street food was a fundamental component of the urban experience."

Roman emperor quiz: Test your knowledge on the rulers of the ancient empire

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus