'Liquid gypsum' burial from Roman Britain scanned in 3D, revealing 1,700-year-old secrets

About 1,700 years ago, liquid gypsum was poured over the remains of an elite family in Roman Britain.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

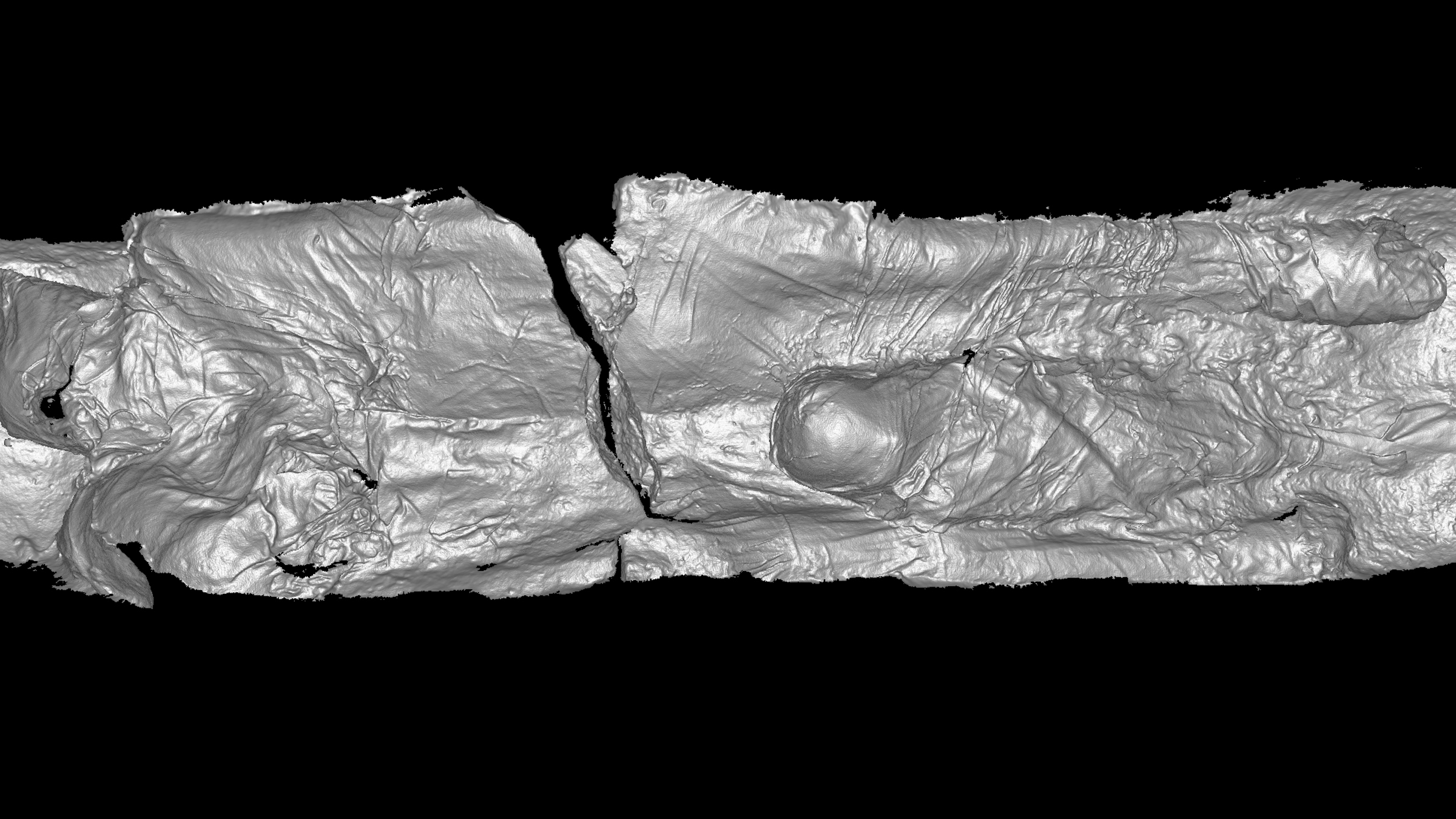

About 1,700 years ago, a wealthy Roman family was buried with a bizarre material — liquid gypsum — poured over their corpses. Now, a noninvasive 3D scan of this burial has revealed the insides of their burial cocoon.

Gypsum is a mineral and key ingredient in cement and plaster that, on rare occasions, Roman-era people used in burials. Once the deceased were placed in lead or stone coffins, liquid gypsum was poured over the bodies, which then hardened into protective shells. After that, the coffins were buried in the ground. Most of the coffins' contents eventually decayed, leaving behind plaster casts with cavities similar to those of the victims discovered at Pompeii.

The scan's finding is "unparalleled," as these gypsum cavities are filled with details, preserving imprints of shrouds, clothes, footwear and even weaving patterns, according to a statement from the University of York in the U.K.

The burial examined, the multibody grave from York, is presumed to be that of a family who died simultaneously around 1,700 years ago. The scan revealed the contours of two adult bodies, as well as that of an infant who had been wrapped in cloth bands. Even the small ties used to bind the burial shroud around one of the adults' heads were visible from the scans.

Related: 1st-century burial holds Roman doctor buried with medical tools, including 'top-quality' scalpels

"The Roman family gypsum casing is particularly valuable because neither the skeletons, nor the coffin, were retained after their discovery in the 19th c[entury]," when there was a building boom in and around the city, project principal investigator Maureen Carroll, chair of Roman archaeology at the University of York, told Live Science in an email.

Remarkably, the casing reveals more than the skeletons could, she said. "We are very lucky to have this casing, as it shows the precise position of the bodies and their relationship to each other exactly at the moment when the liquid gypsum was poured over them and the lid of the coffin closed about 1700 years ago!"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, it's still a mystery why Romans poured gypsum into coffins. Grave goods indicate that gypsum burials were reserved for an elite social class. Traces of aromatic resins from Arabia and the Mediterranean have been discovered in other gypsum burials from York. These resins were luxuries accessible only to the very wealthy.

Archaeologists have also discovered gypsum burials in Europe and North Africa, which were also occupied by the Roman Empire, but the burials are most common from the third and fourth centuries in Britain, with York and the surrounding region sporting about 50 of them — the highest concentration of gypsum burials discovered to date, Carroll said.

"3D scanning has never before been applied to the material in Britain or any of the other gypsum/plaster/chalk burials elsewhere," Carroll noted.

Next, the team plans to scan all 16 gypsum burial cavities in the York museum, in hopes of identifying characteristics of those interred, such as their age, sex, health and region of origin, according to the statement.

The researchers presented their findings, which were done in partnership with the York Museums Trust and Heritage360, on June 3 at the York Festival of Ideas.

Hannah Kate Simon is an archaeologist and art historian with a focus on Roman art and archaeology. Hannah holds a Master's degree in the history of art and archaeology from New York University's Institute of Fine Arts, as well as two bachelor degrees in Art History and Theatre from Indiana University of Pennsylvania. She previously worked at NYU's Grey Art Gallery as a contributor to its exhibition catalogues, interned at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and excavated at Aphrodisias, an ancient Greek City in what is now Turkey.

- Laura GeggelManaging Editor

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus