Roman-era skeletons buried in embrace, on top of a horse, weren't lovers, DNA analysis shows

A new analysis of a double burial in Austria has revealed that a skeletal couple weren't lovers but likely an embracing mother and daughter.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

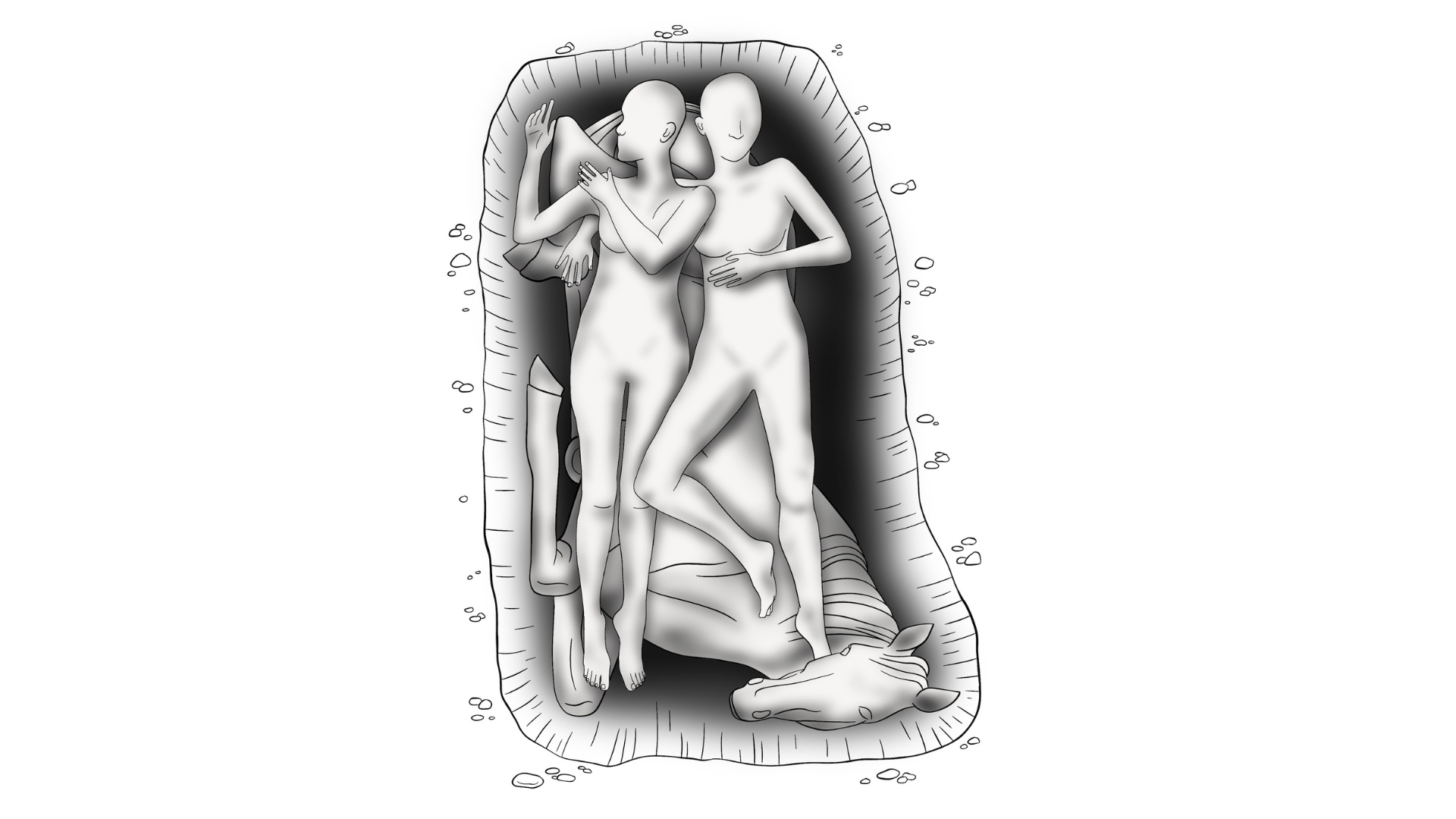

Centuries ago, two people were buried arm in arm on top of a horse in what is now Austria. The unique burial prompted archaeologists to think that the two were a male-female married couple from medieval times. But it turns out they couldn't have been more wrong.

A new analysis of the remains suggests that the couple was actually a mother-daughter pair who died around 1,800 years ago during the Roman era.

"It's the first genetically proven mother-daughter burial in Austria in Roman times," study senior author Sylvia Kirchengast, a professor of evolutionary anthropology at the University of Vienna, told Live Science. "We also disprove a long-held misconception about the kind of relation between the two individuals."

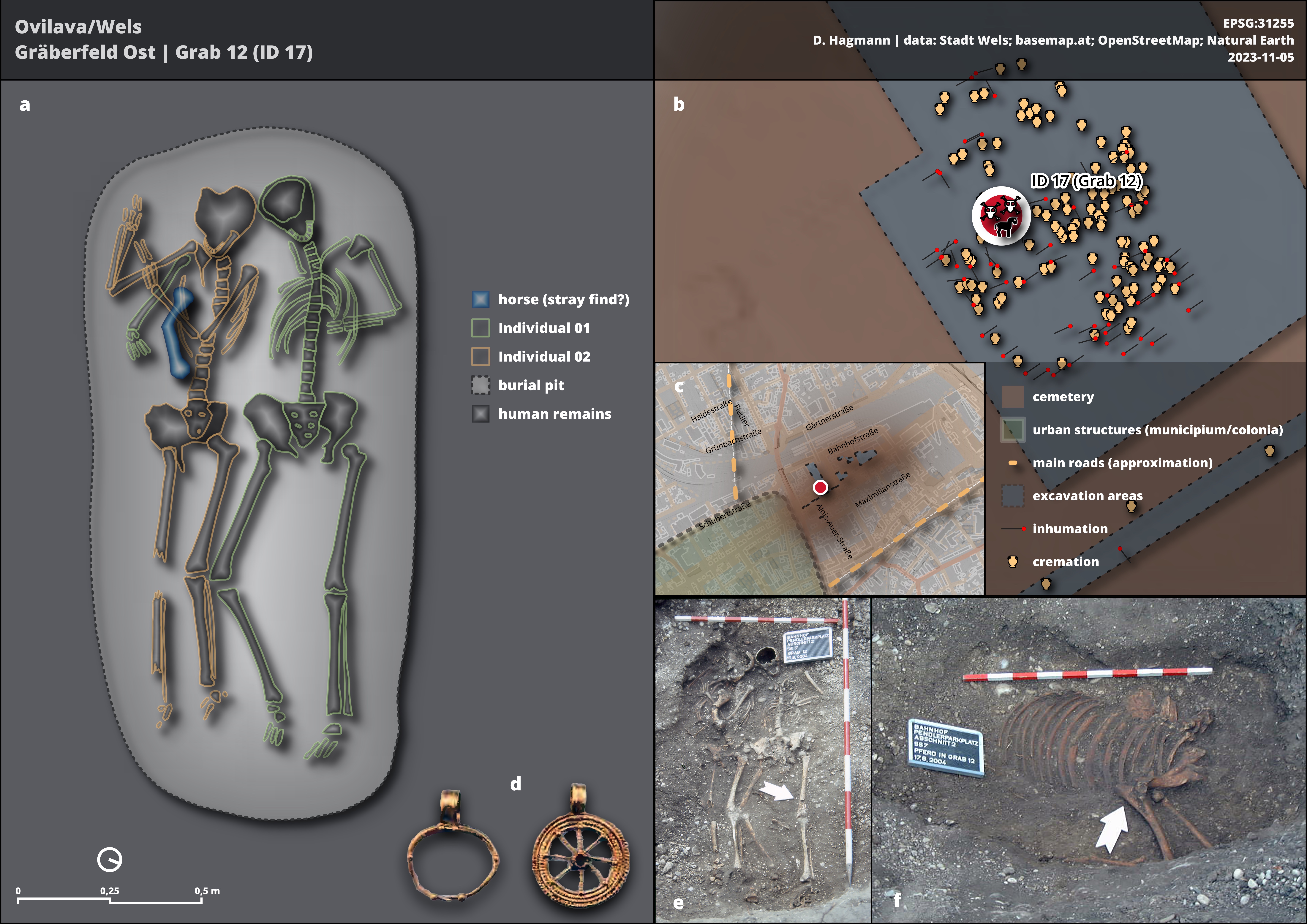

Archaeologists excavated the three skeletal remains (the two humans and one horse) — along with two golden pendants in the shape of a wheel and a crescent moon — in 2004 from a cemetery in the ancient Roman city of Ovilava, today known as Wels in the state of Upper Austria. The right arm of one individual lay around the other's shoulder, indicating a close social and emotional connection between the two individuals. An initial analysis classified the burial as Bavarian from the sixth to seventh centuries A.D. based on grave depth, a west-east orientation that is commonly seen in Bavarian burials and the fact that Germanic Bavarians lived there in the early seventh century.

In the new study the researchers re-evaluated the remains via radiocarbon dating, ancient DNA analysis and a visual inspection. They found that the bones belonged to individuals whose ages at death were 20 to 25 and 40 to 60 years old and lived around A.D. 200 when the Roman Empire held sway over the region. In a twist, both human skeletons turned out to be females, according to an anatomical analysis. DNA results confirmed their biological female status and showed they were first-degree relatives — meaning they were either sisters or mother and daughter, according to the study, which was published in the May issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Related: 'Exceptional' 1,800-year-old sarcophagus unearthed in France held woman of 'special status'

Due to the pair's DNA results, their age difference and other factors, the researchers concluded that individuals were mother and daughter, with the daughter embracing the mother in the grave. "It's very unlikely that two sisters have an age difference of 20 years during those times. So we felt that it's more likely that they are a mother-daughter pair," Kirchengast said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The inclusion of a horse and gold pendants strongly hints that the women were of high social status. It also indicates they were non-Roman elites. "To our knowledge it's extremely uncommon for Roman people to be buried with horses. They were not a 'horse-people'," study lead author Dominik Hagmann, an archaeologist at University of Vienna, told Live Science. He suspected these two individuals were from a Celtic culture still existing in Roman times. The Celts were more commonly buried horses with their owners.

There are other signs that the deceased were familiar with horses. "What I find odd is that the older skeleton shows signs of frequent horse riding," Kirchengast said. "Maybe both women were enthusiastic horse-riders."

Katy Knortz, a doctoral student in classical art and archaeology at Princeton University who was not involved in the study, said that although the possibility of both women being sisters cannot be summarily rejected, the protective positioning of the skeletons and the large difference in age makes the mother-daughter relationship more likely. "I think the reasoning used to determine a mother-daughter relationship is sound, given the typical age for child bearing women in the Roman period," Knortz told Live Science in an email.

Annalisa Marzano, a professor of classical archaeology at the University of Bologna who was not involved in the study, also thought the mother-daughter relationship was the most probable scenario. "In light of the estimated age difference of 15-20 years, the mother-daughter option is the most likely," she told Live Science in an email.

Soumya Sagar holds a degree in medicine and used to do research in neurosurgery at the University of California, San Francisco. His work has appeared in New Scientist, Science, Discover, and Mental Floss. He is a passionate science writer and a voracious consumer of knowledge, especially trivia. He enjoys writing about medicine, animals, archaeology, climate change, and history. Animals have a special place in his heart. He also loves quizzing, visiting historical sites, reading Victorian literature and watching noir movies.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus