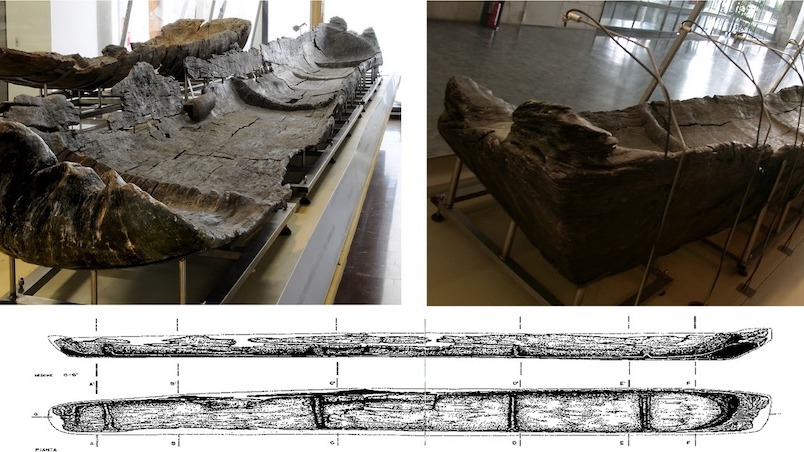

7,000-year-old canoes from Italy are the oldest ever found in the Mediterranean

The wooden vessels were likely used by Neolithic people for fishing and transport.

Five canoes found at the bottom of a lake in Italy were used more than 7,000 years ago for fishing and transport by people living in a Neolithic village near what is now Rome.

Archaeologists discovered the boats at La Marmotta, a prehistoric coastal settlement that is now underwater, while conducting ongoing excavations, according to a study published Wednesday (March 20) in the journal PLOS One.

The large dugout canoes — which were constructed of alder, oak, poplar and European beech — were built between 5700 and 5100 B.C., radiocarbon dating revealed.

The boats are the oldest ever found in the Mediterranean, according to a statement.

"One of the smallest [boats] was probably used for fishing," study co-author Mario Mineo, an archaeologist and director coordinator at the Museum of Civilization in Rome, told Live Science in an email. "The two largest measured almost 11 meters long by 1.2 m wide [36 feet by 4 feet] and it is probable that — thanks also to the easy access to the Tyrrhenian coast via the Arrone river — they could have been used for further trade."

The boat builders also used "advanced construction techniques" to craft the vessels. For example, they incorporated transverse reinforcements, which would have increased the durability of the canoes' hulls, according to the statement.

Related: Dozens of Neolithic burials and 'sacrificed' urns and ax found in France

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The construction techniques and materials used indicate a sophisticated understanding of boat-building and navigation," senior study author Niccolò Mazzucco, a senior researcher in the Department of Civilizations and Forms of Knowledge at the University of Pisa in Italy, told Live Science in an email. "[This] is significant because it showcases the ingenuity and skill of ancient peoples in utilizing natural resources to create efficient means of transportation."

For example, the researchers think the vessels may have been equipped with "sails or outriggers," or parallel support floats, Mazzucco said. This can be evidenced by three T-shaped wooden objects found at the site near the canoes. Each of these items contained various holes, which were likely used to "fasten ropes tied to sails or other nautical elements," according to the statement.

"Such advancements suggest a deeper comprehension of maritime technology and navigation, with vessels equipped for long-distance voyages," Mazzucco added. "However, our current understanding falls short of precisely identifying the types of boats used, their construction methods and how components like canoes and T-shaped wooden objects were mounted together — whether through ropes, wooden pegs or other means."

The builders' ability to include multiple types of wood in their creations is also noteworthy, as it shows that they knew which "trees could be used to make the dugouts," Mazzucco said. "In contrast, at other [Neolithic] sites where more than one canoe has been found, the same [tree] species was usually used for all of them."

In addition to the boats, archaeologists found numerous artifacts scattered around the site, including flint and obsidian tools, pottery vessels, figurines and ornaments, according to the study.

In 2022, the researchers also found 52 wooden sickles at the site that were used for harvesting cereal grains.

"These artifacts offer further insights into the daily lives, symbolic and technological capabilities of the ancient inhabitants," Mazzucco said. "No other site in the Mediterranean presents such [an] amount of harvesting tools."

Editor's Note: This story was corrected at 11 a.m. EDT on March 22 to note that the canoes were found in a lake and not the Mediterranean Sea.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus