Modern humans migrated into Europe in 3 waves, 'ambitious and provocative' new study suggests

Modern humans migrated into Europe in three waves: 54,000, 45,000 and 42,000 years ago, a new study claims.

It was long thought that modern humans first ventured into Europe about 42,000 years ago, but newly analyzed tools from the Stone Age have upended this idea. Now, evidence suggests that modern humans trekked into Europe in three waves between 54,000 and 42,000 years ago, a new study finds.

Our species, Homo sapiens, arose in Africa more than 300,000 years ago, and anatomically modern humans emerged at least 195,000 years ago. Evidence for the first waves of modern humans outside Africa dates back at least 194,000 years to Israel, and possibly 210,000 years to Greece.

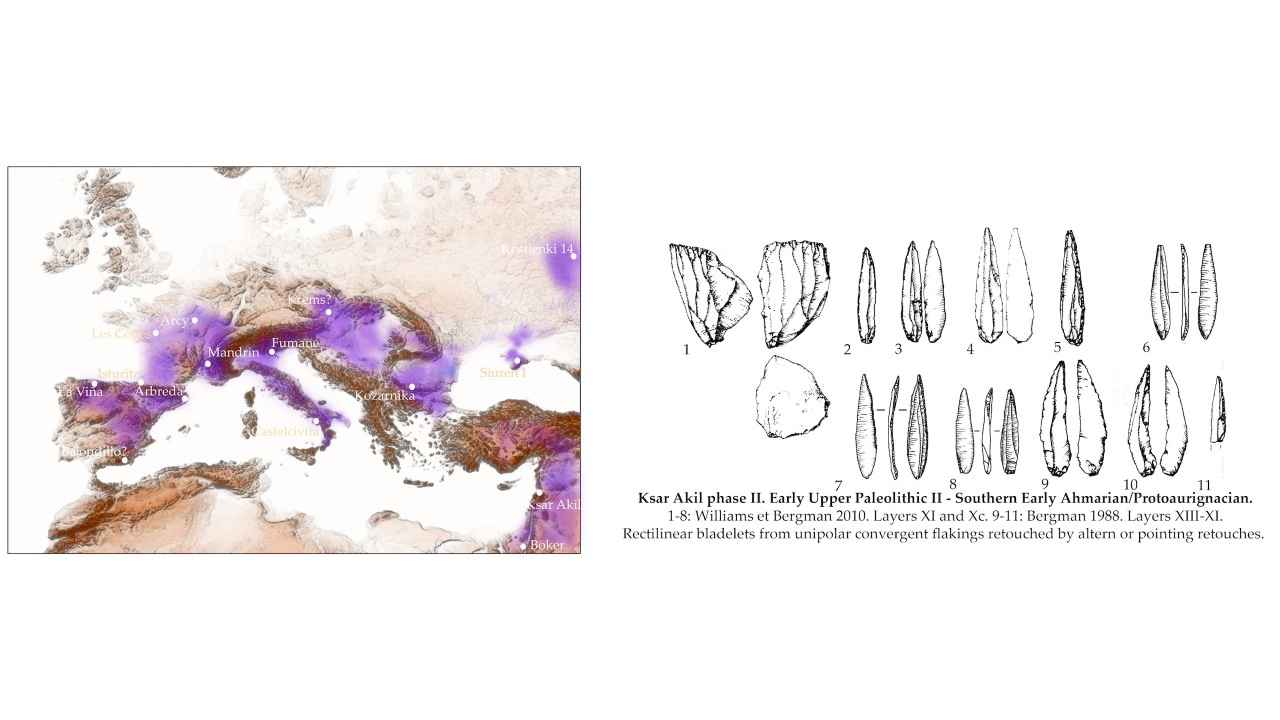

For years, the oldest confirmed signs of modern humans in Europe were teeth about 42,000 years old that archaeologists had unearthed in Italy and Bulgaria. These ancient groups were likely Protoaurignacians — the earliest members of the Aurignacians, the first known hunter-gatherer culture in Europe.

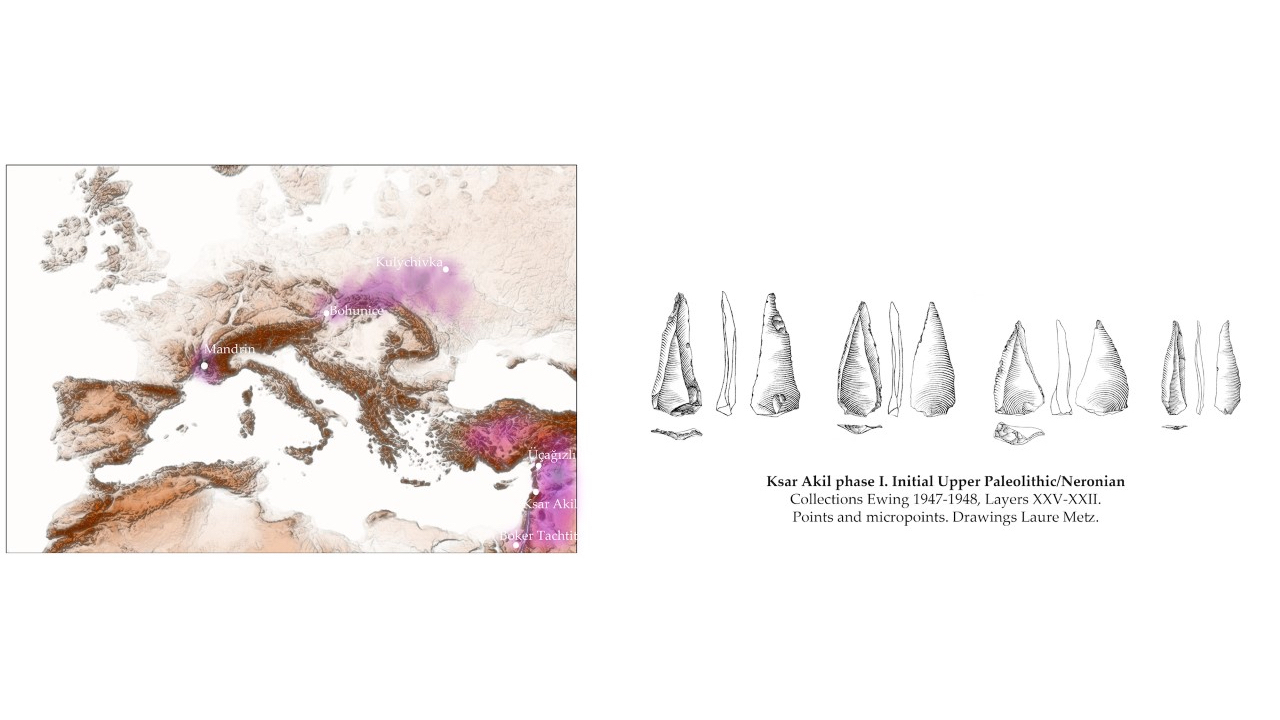

However, a 2022 study revealed that a tooth found in the site of Grotte Mandrin in southern France's Rhône Valley suggested that modern humans lived there about 54,000 years ago, a 2022 study found. This suggested Europe was home to modern humans about 10,000 years earlier than previously thought.

In the 2022 study, scientists linked this fossil tooth with stone artifacts that scientists previously dubbed Neronian, after the nearby Grotte de Néron site. Neronian tools include tiny flint arrowheads or spearpoints and are unlike anything else found in Europe from that time.

Related: Prehistoric population once lived in Siberia, but mysteriously vanished, genetic study finds

Now, in a new study, an archaeologist argues that another wave of modern humans may have entered Europe between the 42,000-year-old Protoaurignacians and the 54,000-year-old Neronians. "It's an in-depth rewriting of the historical structure of [the] arrival of sapiens in the continent," study lead researcher Ludovic Slimak, an archaeologist at the University of Toulouse in France, told Live Science in an email. He detailed his ideas in a study published on Wednesday (May 3) in the journal PLOS One.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stone Age evidence

Slimak focused on a group or "industry" of stone artifacts previously unearthed in the Levant, the eastern Mediterranean region that today includes Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria. Scientists have long thought that the Levant was a key gateway for modern humans migrating out of Africa.

When Slimak compared Neronian tools from Grotte Mandrin with the industry from about the same time from a site known as Ksar Akil in Lebanon, he found notable similarities. This suggested both groups were one and the same, with the Levantine group expanding into Europe over time. The much younger Protoaurignacian artifacts also have very similar counterparts in the Levant from a culture known as the Ahmarian, Slimak noted.

"I buil[t] a bridge between Europe and the East Mediterranean populations during the early migrations of sapiens in the continent," Slimak said.

In addition, Slimak found thousands of modern human flint artifacts from the Levant that existed in the period known as the Early Upper Paleolithic, between the Ksar Akil and the Ahmarian ones. This led him to look for possible modern human counterparts of these artifacts in Europe.

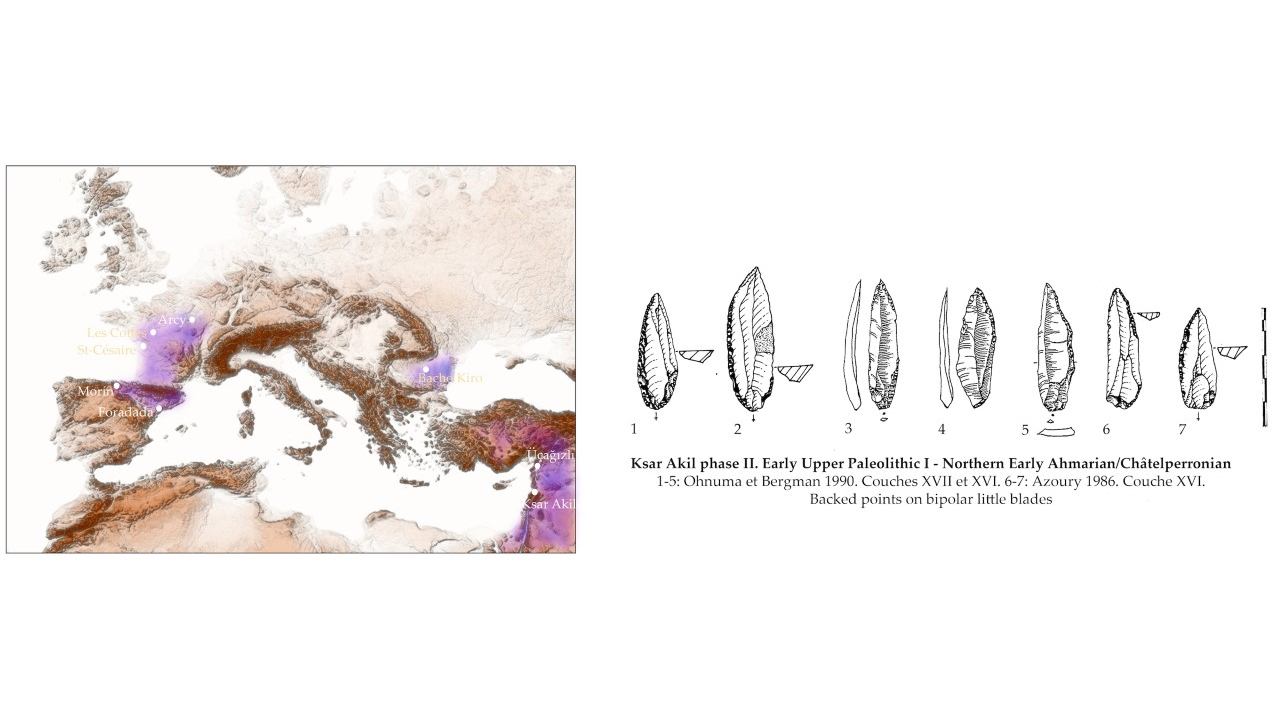

Stone artifacts from a European industry known as the Châtelperronian highly resemble modern human artifacts seen in the Early Upper Paleolithic of the Levant. In addition, Châtelperronian items date to about 45,000 years ago, or between those of the Neronians and the Protoaurignacians. However, scientists had often thought Châtelperronians were Neanderthals.

Slimak now argues the Châtelperronians were actually a second wave of modern humans into Europe. "We have here, and for the first time, a serious candidate for a non-Neanderthalian origin of these industries," Slimak said.

This new model of modern human settlement of Europe is "ambitious and provocative," Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London who did not take part in the new study, told Live Science in an email. "Evidence has been building for a while that there were several early dispersals of Homo sapiens into Europe before the well-attested Aurignacian-associated one about 42,000 years ago."

Future research can help confirm or disprove this new idea. "I see this paper generating a number of research projects to support or refute it," Christian Tryon, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Connecticut who helped translate the new study, told Live Science in an email. "People now need to look at some of the archaeological sites here with a critical eye to see if they see the same kinds of technical details reported by Slimak. This is the start of a long process, I suspect."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus