Hirota people of Japan intentionally deformed infant skulls 1,800 years ago

The Hirota people, who occupied a Japanese island for around 400 years, deliberately flattened the back of their children's heads. And experts are not entirely sure why.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For 400 years, a group of Indigenous people living in Japan deliberately deformed the skulls of their infant children, a new study suggests.

The Hirota people resided on the southern Japanese island of Tanegashima between the end of the Yayoi period and the Kofun period, or between the third and seventh centuries. Between 1957 and 1959, and later between 2005 and 2006, researchers excavated numerous skeletons from a Hirota site on Tanegashima and found that most had deformed skulls.

Until now, it was unclear if the skulls had been deformed by an unknown natural process or deliberately misshaped via a process known as artificial cranial deformation (ACD), which normally involves wrapping or pressing an infant's skull to change its shape shortly after birth. (ACD is also known as intentional skull deformation; however, this term is used less often, as most individuals do not make this decision themselves.)

In a new study, published Wednesday (Aug. 16) in the journal PLOS One, researchers reanalyzed the skulls and compared them with Japanese remains from the same time period. Their results indicate that ACD is the most likely explanation for the contorted craniums.

Related: Ancient bones reveal previously unknown Japanese ancestors

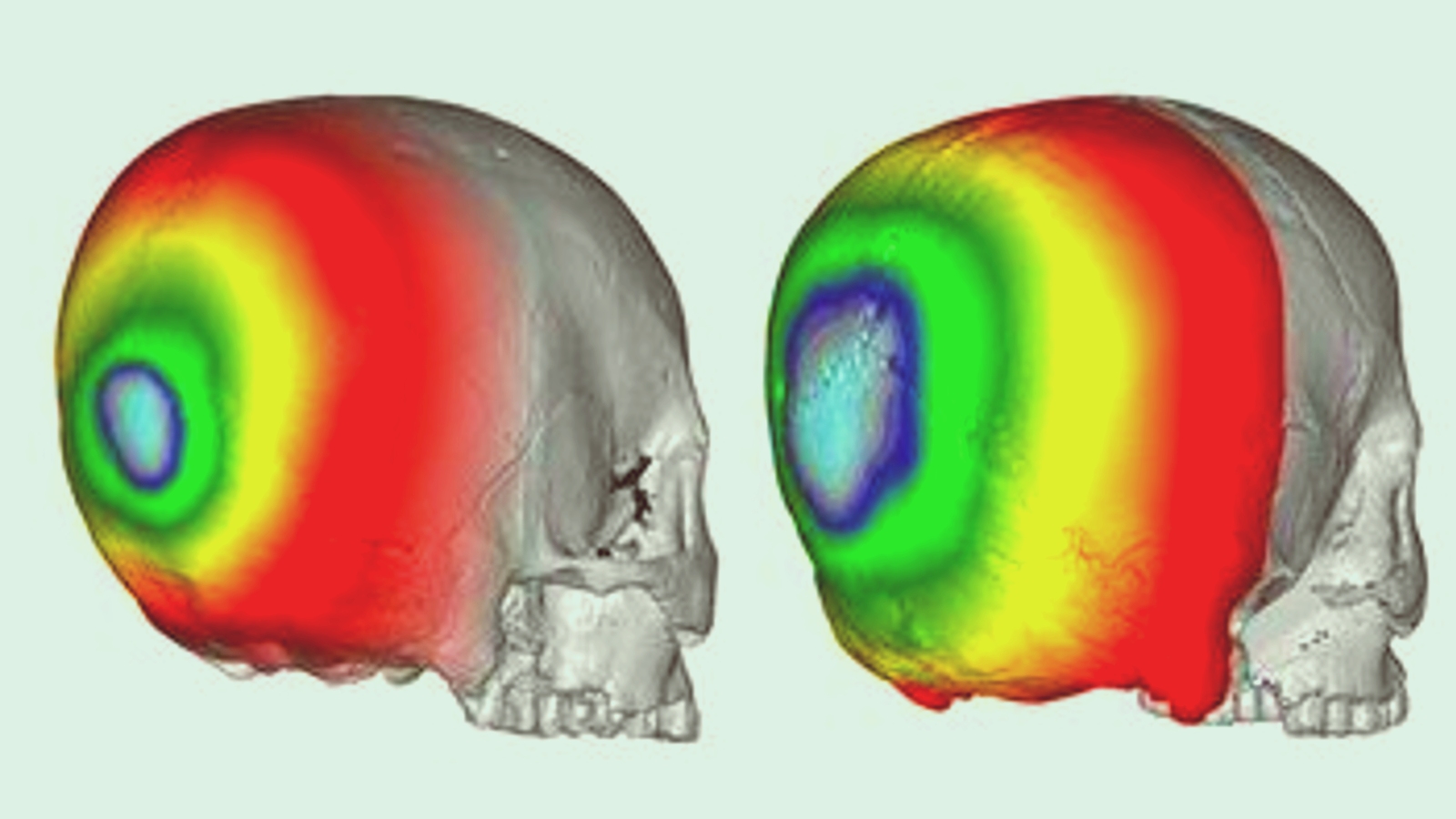

The research team analyzed the overall 2D skull shape and took 3D scans of the bones. Then, they compared the skulls with those from the Yayoi and Jomon peoples, who occupied other parts of Japan around the same time.

All of the deformed Hirota remains had been altered to create a slightly shortened head with a flattened back of the skull. The analysis revealed very similar damage to the occipital bone at the base of each skull and showed "depressions in parts of the skull that connects the bones together," study lead author Noriko Seguchi, a biological anthropologist at Kyushu University in Japan, said in a statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An equal number of male and female remains were deformed, and there was no difference between the sexes in the shapes of the skulls. Similar deformations were not observed among the Yayoi or Jomon skulls. The distinct morphology of the Hirota skulls "strongly suggests intentional cranial modification," Seguchi said.

It's unknown why the Hirota people chose to alter their infants' skulls. One possibility is that it helped them distinguish themselves from other groups, the researchers wrote in the statement. The team plans to examine more archaic deformed skulls from the region to gain further insight into why ACD was carried out.

Evidence of ACD has been uncovered in many groups throughout history, including the Huns, medieval European women, the Maya, some Native American tribes, and people from the ancient Paracas culture in what is now Peru, whose exceptionally elongated skulls have been misconstrued by conspiracy theorists as evidence of aliens, Discover magazine reported in a 2022 feature on ACD.

ACD is still practiced today, primarily in the Pacific nation of Vanuatu, where individuals' skulls are deformed to appear more similar to one of their deities, who is depicted with an elongated head. On rare occasions, some girls in parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo have their heads elongated at birth as a status symbol, Discover magazine reported.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus