45,000-year-old bones unearthed in cave are oldest modern-human remains in Central Europe

The finding suggests that 'successive pulses of small groups' of humans replaced Neanderthals in Europe starting around 45,000 years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Modern humans crossed the Alps into chilly Northern Europe about 45,000 years ago, meaning they may have coexisted with Neanderthals in Europe for thousands of years longer than experts previously thought, according to new research.

The discovery — of 13 bone fragments belonging to Homo sapiens who occupied a cave in Germany between about 44,000 and 47,500 years ago — catalogs the oldest known H. sapiens remains from Central and Northwest Europe, the researchers said. The finding also surprised the team because, as they found, the climate in the region was frigid at that time.

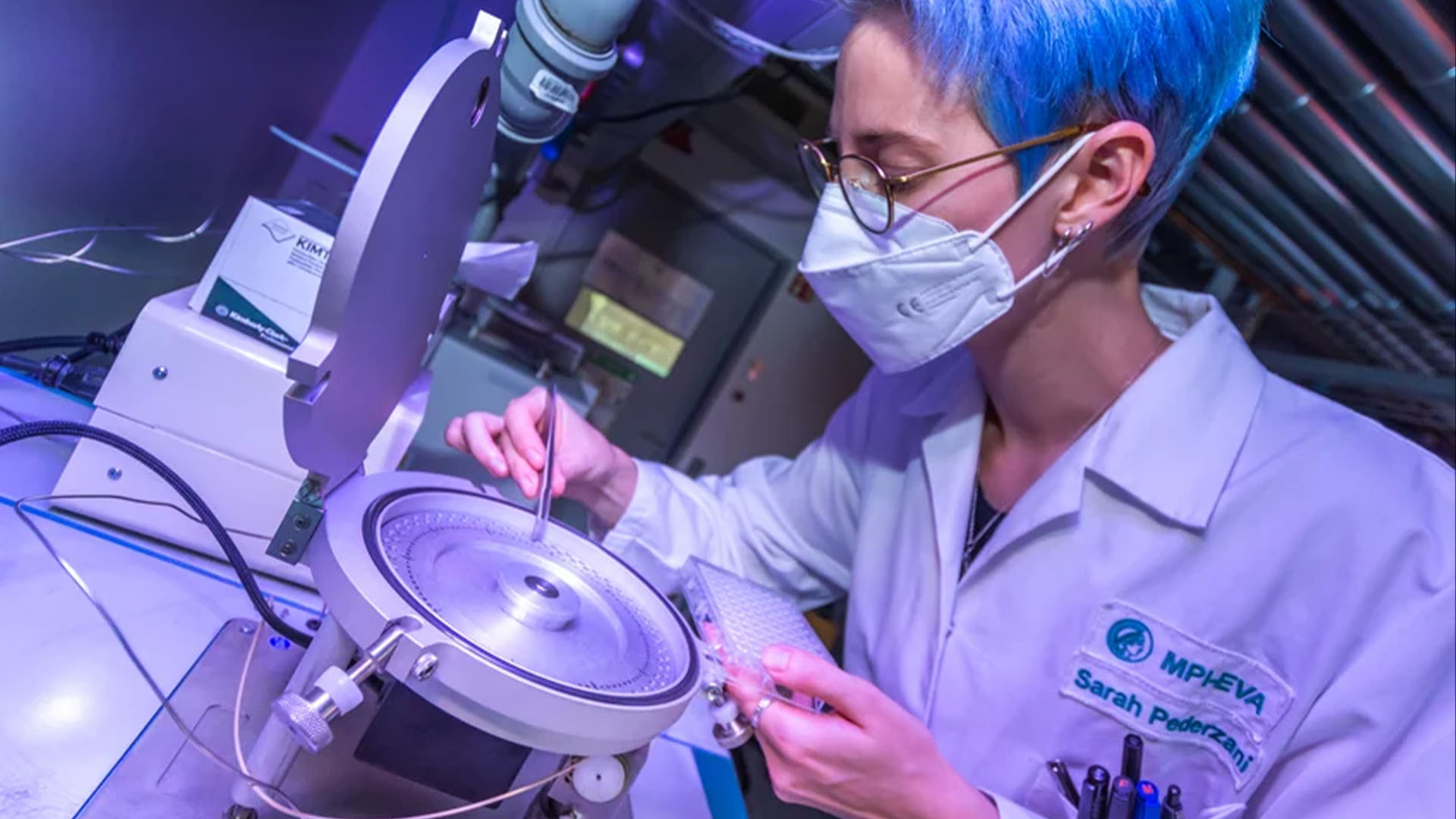

"This shows that even these earlier groups of Homo sapiens dispersing across Eurasia already had some capacity to adapt to such harsh climatic conditions," Sarah Pederzani, an archaeologist at the University of La Laguna in Spain and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany who led the paleoclimate study of the site, said in a statement.

Related: Modern humans migrated into Europe in 3 waves, 'ambitious and provocative' new study suggests

When H. sapiens arrived in Europe, they were not the first human lineage to enter the continent. Neanderthals — our closest extinct relative, which was well-adapted to the cold — occupied Europe from at least 200,000 years ago until they went extinct around 40,000 years ago.

Prior work discovered that H. sapiens entered Southwest Europe by 46,000 years ago. Much remains hotly debated about the nature of the interactions between H. sapiens and Neanderthals during this period, called the Middle-to-Upper Paleolithic transition (47,000 to 42,000 years ago), and how much our species might have sped up the Neanderthals' demise.

To investigate this mysterious transitional period, the researchers of three new studies examined artifacts and the climate from that time, according to their findings, published online Wednesday (Jan. 31) in the journal Nature and in two studies in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Archaeologists previously unearthed a number of different "industries," or stone tool manufacturing styles, dating to this period — including the Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician (LRJ) industry — but it was unclear whether H. sapiens or Neanderthals had crafted them.

"The Middle Paleolithic in Europe [about 300,000 to 35,000 years ago] is linked with Neanderthals, while the Upper Paleolithic in Europe [about 35,000 to 10,000 years ago] is linked with modern H. sapiens," study co-author Jean-Jacques Hublin, a paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, told Live Science. "The artifacts of the transitional period have sort of mixed features."

In one of the new studies, researchers examined LRJ artifacts, which included elaborately crafted, leaf-shaped stone tools that were widespread in Northern Europe from Germany to Britain.

The scientists focused on thousands of bone fragments associated with LRJ artifacts in Ilsenhöhle (Ilse's cave) in Ranis, Germany. The researchers not only conducted new excavations at the site but also performed new analyses of remains found in the cave in the 1930s that are now in museum collections.

One of the new studies found the cave was used intermittently not only by denning hyenas and hibernating cave bears but also small groups of hominins — likely either H. sapiens or Neanderthals — who dined on reindeer, woolly rhinoceroses and horses. However, many bone fragments there were too small and broken for researchers to identify them by their shape. Instead, the researchers analyzed proteins and DNA extracted from these remains to determine the bones' origins.

Their research uncovered the 13 bone fragments from about 44,000 to 47,500 years ago.

Related: Scientists finally solve mystery of why Europeans have less Neanderthal DNA than East Asians

"The common wisdom was these transitional assemblages of artifacts were made mostly by late Neanderthals," Hublin said. "What we find with the LRJ is that it was not made by Neanderthals but by Homo sapiens moving into Europe much earlier than we thought."

Analyzing animal teeth and bones from the cave suggested that when humans lived there, the area had very cold climates and steppe or tundra landscapes similar to those found in Siberia or northern Scandinavia today.

"Until recently it was thought that resilience to cold-climate conditions did not appear until several thousand years later, so this is a fascinating and surprising result," Pederzani said in the statement. "Perhaps cold steppes with larger herds of prey animals were more attractive environments for these human groups than previously appreciated."

These findings reveal that H. sapiens arrived in Northwest Europe several thousand years before Neanderthals disappeared in Southwest Europe — a clue that the two groups may have interacted. "So we now have another important piece of what is a complicated puzzle" about the nature of the interactions between H. sapiens and Neanderthals, William Banks, an archaeologist with the French National Center for Scientific Research who did not take part in this study but wrote an editorial about it, told Live Science.

"These findings suggest that instead of H. sapiens replacing Neanderthals in Europe in a rapid east-to-west wave as previously thought, "we see Homo sapiens colonized the northern part of Europe first and lived there for several millennia on the periphery of the Neanderthal world," Hublin said. "I would say Homo sapiens probably lived in these rather hostile environments because they had technical capabilities to adapt there. We don't see one wave of Homo sapiens moving into Europe and replacing Neanderthals, but successive pulses of small groups moving into new territory, and then after several millennia finally completely replacing Neanderthals."

Future research can investigate whether other Middle-to-Upper Paleolithic transition industries whose origins currently remain uncertain came from H. sapiens, Hublin said. "I would also like to examine Neanderthal remains from after contact with Homo sapiens, to see if there's any signs of Homo sapiens DNA in them," he added.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus