Ultra-rare whale never seen alive washes up on on New Zealand beach — and scientists could now dissect it for the 1st time

A beaked whale that recently washed up dead on a New Zealand beach likely belongs to the world's rarest cetacean species. If confirmed, researchers could dissect the species for the very first time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A mysterious dead whale that recently washed up on a New Zealand beach may belong to the world's rarest cetacean species, spade-toothed whales, which are so elusive they have never been seen alive. If this is the case, the newfound specimen will give scientists a rare chance to study the creatures we know next to nothing about.

Beachgoers discovered the 16.5-foot-long (5 meters) carcass July 4 on the shore near Taieri Mouth — a village in the Otago region of New Zealand's South Island. Wildlife experts from the country's Department of Conservation (DOC), recovered the remains and took DNA samples, which have been sent to the University of Auckland for analysis, according to a DOC statement.

Researchers from DOC and the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa believe the animal is a spade-toothed whale (Mesoplodon traversii). However, they will not know for sure until the DNA samples are analyzed, which could take "several weeks or months," DOC representatives said. The remains are currently being preserved in cold storage.

Spade-toothed whales belong to a group known as beaked whales, which look like a mix between whales and dolphins. Beaked whales are the deepest-diving mammals on Earth and are capable of holding their breath for hours at a time, which makes them extremely hard to find and track.

If confirmed, the newly washed-up whale will be the sixth known spade-toothed specimen found in the last 150 years, of which only two others have been fully intact. To date, there have been no confirmed live sightings of the species.

"Spade-toothed whales are one of the most poorly known large mammalian species of modern times," Gabe Davies, a DOC coastal operations manager for Otago, said in the statement. "From a scientific and conservation point of view, this is huge."

Related: 10 creatures that washed up on the world's beaches in 2023

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

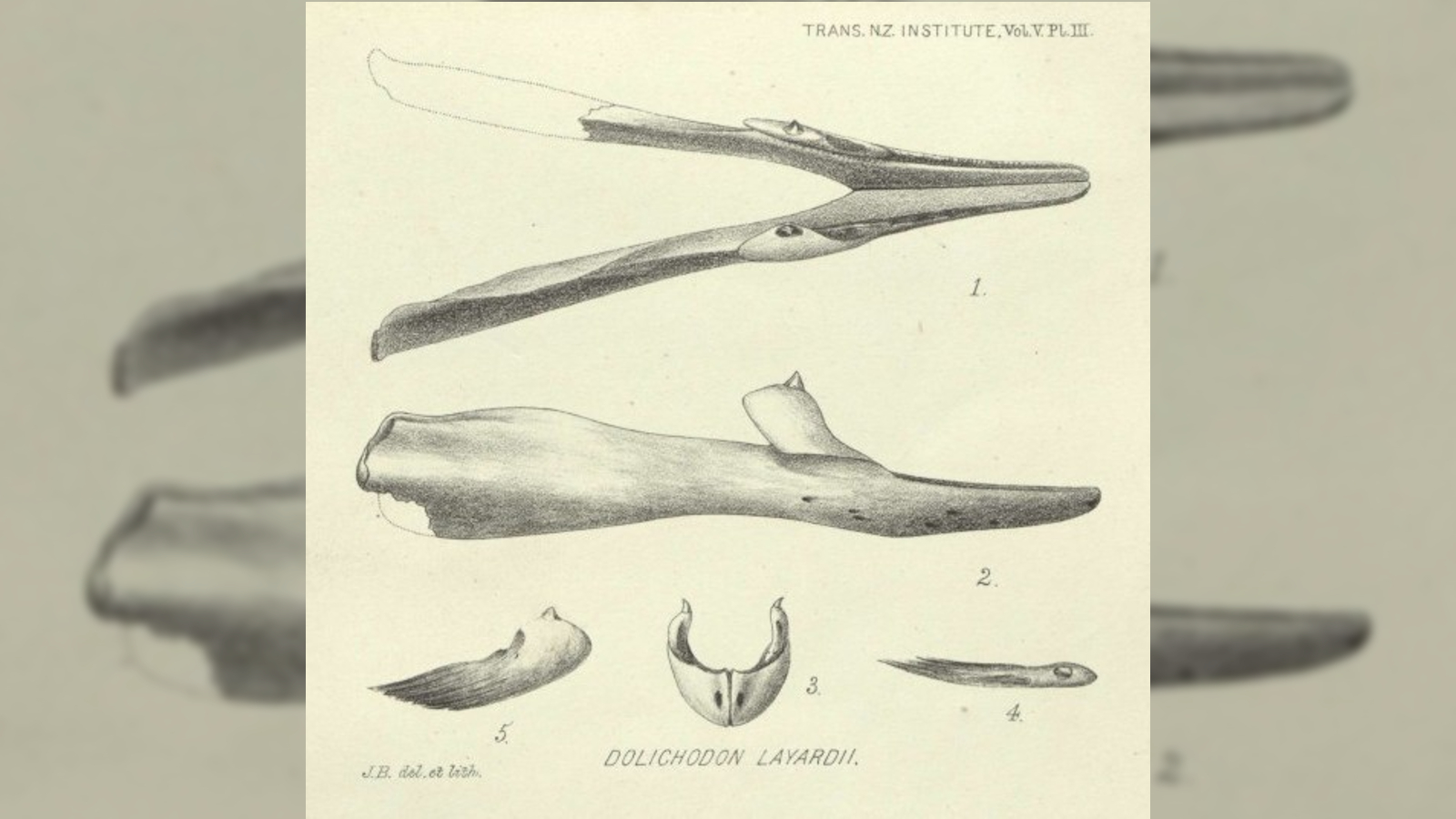

Spade-toothed whales were officially described in a 2002 study, which revealed that three whale bones found in New Zealand and Chile between 1873 and 1993 shared the same DNA that was unknown to science. The first intact specimens were found in 2010 when a suspected mother and calf washed up dead at Opape Beach in New Zealand's North Island.

Almost nothing is known about the species. However, researchers believe they probably share characteristics with other beaked whales from the genus Mesoplodon, such as extremely rare Sowerby's beaked whales (Mesoplodon bidens), which spend most of their time diving in the deep sea to hunt for squid, according to Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC).

Spade-toothed whales likely live exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere and are probably only found in the South Pacific Ocean, according to WDC.

If the new specimen is a spade-toothed whale, this will be the first chance that researchers have to dissect the species because the other intact specimens that washed up at Opape Beach were buried before genetic analysis confirmed their identity, AP News reported — meaning the opportunity to study them was lost.

Any dissection of the specimen will be carried out under the supervision of the local rūnaka — a Māori tribal council, DOC representatives wrote. This will be done to honor a non-legally-binding treaty signed by Māori leaders and several Polynesian Indigenous groups in March, which recognizes whales as "legal persons."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus