Tiny, highly venomous jellyfish stings 2 people in the middle of the ocean — forcing them to be airlifted to hospital

Irukandji jellyfish, which are around the same size as a dime, have a venom-filled sting that can trigger an extremely painful and occasionally deadly syndrome.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Two fishers from Australia were recently airlifted to hospital after being stung by one of the most venomous jellyfish in the world while they were far out on the ocean.

The two unnamed men were on a boat around 12 miles (19 kilometers) off the coast of Dundee Beach in Australia's Northern Territory when they were stung by an Irukandji jellyfish on Oct. 10, Australian news site 7News reported.

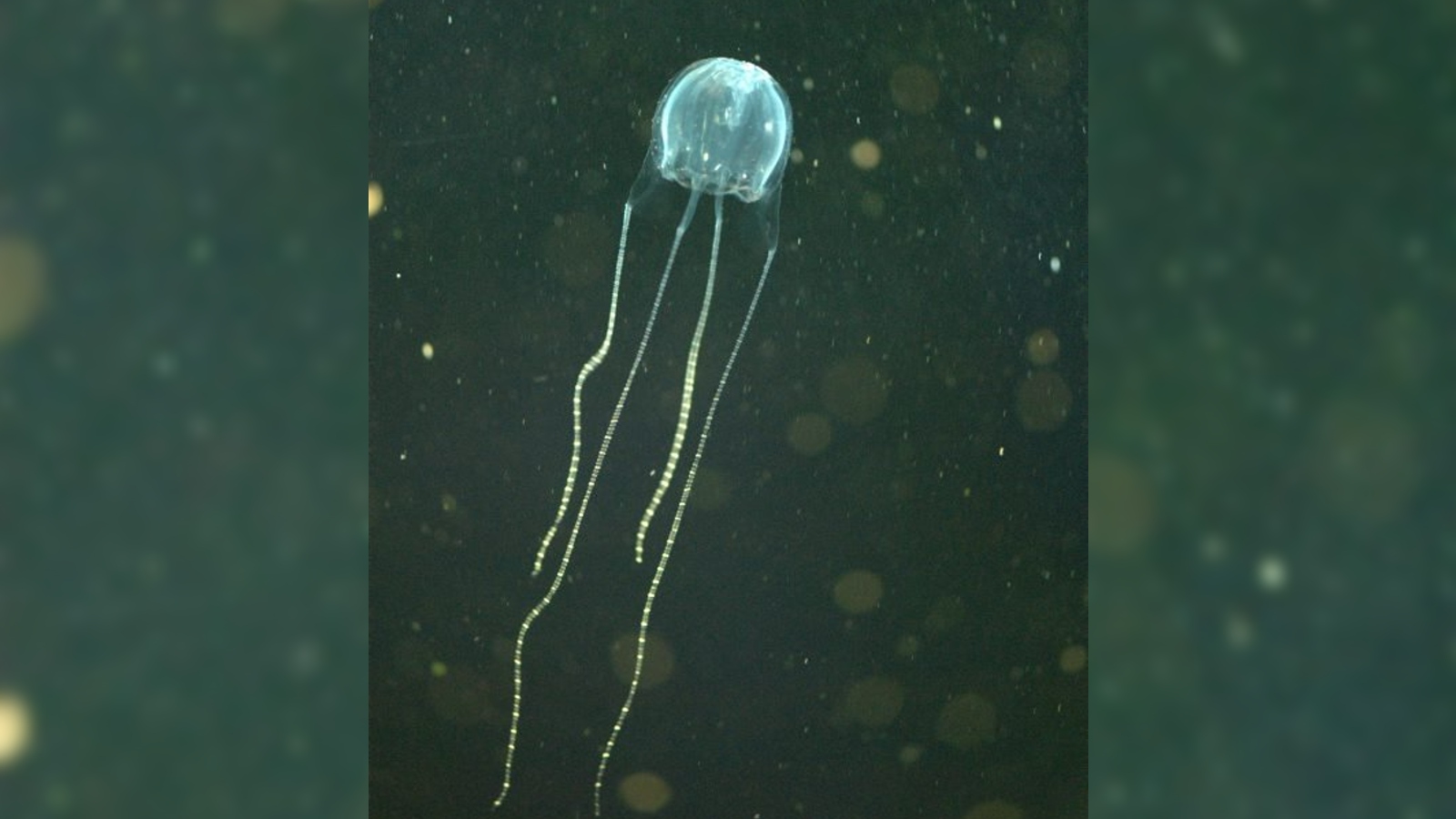

There are 16 known species of Irukandji jellyfish, which are all endemic to the deep seas around northern Australia. The venom of each of these tiny box jellyfish can trigger Irukandji syndrome — an extremely painful and potentially deadly set of reactions.

It is unclear which species stung the two fishers, but most cases of Irukandji syndrome are caused by Carukia barnesi, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The species is only around 0.8 inch (2 centimeters) long but is one of the most venomous marine creatures on Earth.

The two men were airlifted to hospital from their boat and were discharged 48 hours later. Both are expected to make a full recovery, 7News reported.

Related: What's the difference between poison and venom?

C. barnesi administer their toxins using specialized stinging cells, known as nematocysts, which line their four tentacles and fire venom-filled barbs into their prey or as a defense mechanism against predators, according to the Australian Museum. Due to their small size, most people are unaware of the jellyfish until they have been stung.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Irukandji venom works in a similar way to tetrodotoxin, one of the world's most potent venoms that is administered by animals such as pufferfish and blue-ringed octopuses, according to NCBI. Both toxins stop nerves from properly signaling to muscles by blocking sodium ion channels.

The symptoms of Irukandji syndrome include shooting pains in muscles, backache, headache, nausea, vomiting, anxiety, hypertension, breathing problems and cardiac arrest, according to NCBI. Although most people make a full recovery, there are cases of people continuing to experience pain up to a year later. Symptoms can begin as soon as five minutes after being stung, according to the Queensland Ambulance Service (QAS).

Like with tetrodotoxin, there is no known antivenom for Irukandji venom, and treatment is only supportive, according to NCBI. Experts recommend immediately dousing the sting area with vinegar because its acidic properties can prevent the barbs from releasing their venom, according to QAS.

On average, there are between 50 and 100 cases of Irukandji syndrome in Australia every year, according to NCBI. Most cases occur in the summer when warmer waters and high winds push the jellyfish to the surface and toward land, but cases have been documented in every calendar month. Two people — an American scientist and a British tourist — are known to have died from Irukandji syndrome, Scientific American previously reported.

Another two people, both French tourists, are suspected of being killed by Irukandji stings in a single snorkelling incident, Australian news site ABC News previously reported. But they were both elderly and had underlying health conditions, which made it hard to determine an exact cause of death.

Australia is also home to several of the world's most venomous sea creatures, including other box jellyfish, stonefish and blue-ringed octopuses, each of which have killed multiple people.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus