Giant phantom jelly: The 33-foot-long ocean giant that has babies out of its mouth

Giant phantom jellies were discovered in 1899 and since then have only been spotted around 120 times.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Name: Giant phantom jelly (Stygiomedusa gigantea)

Where it lives: Every ocean except the Arctic Ocean

What it eats: Plankton and small fish

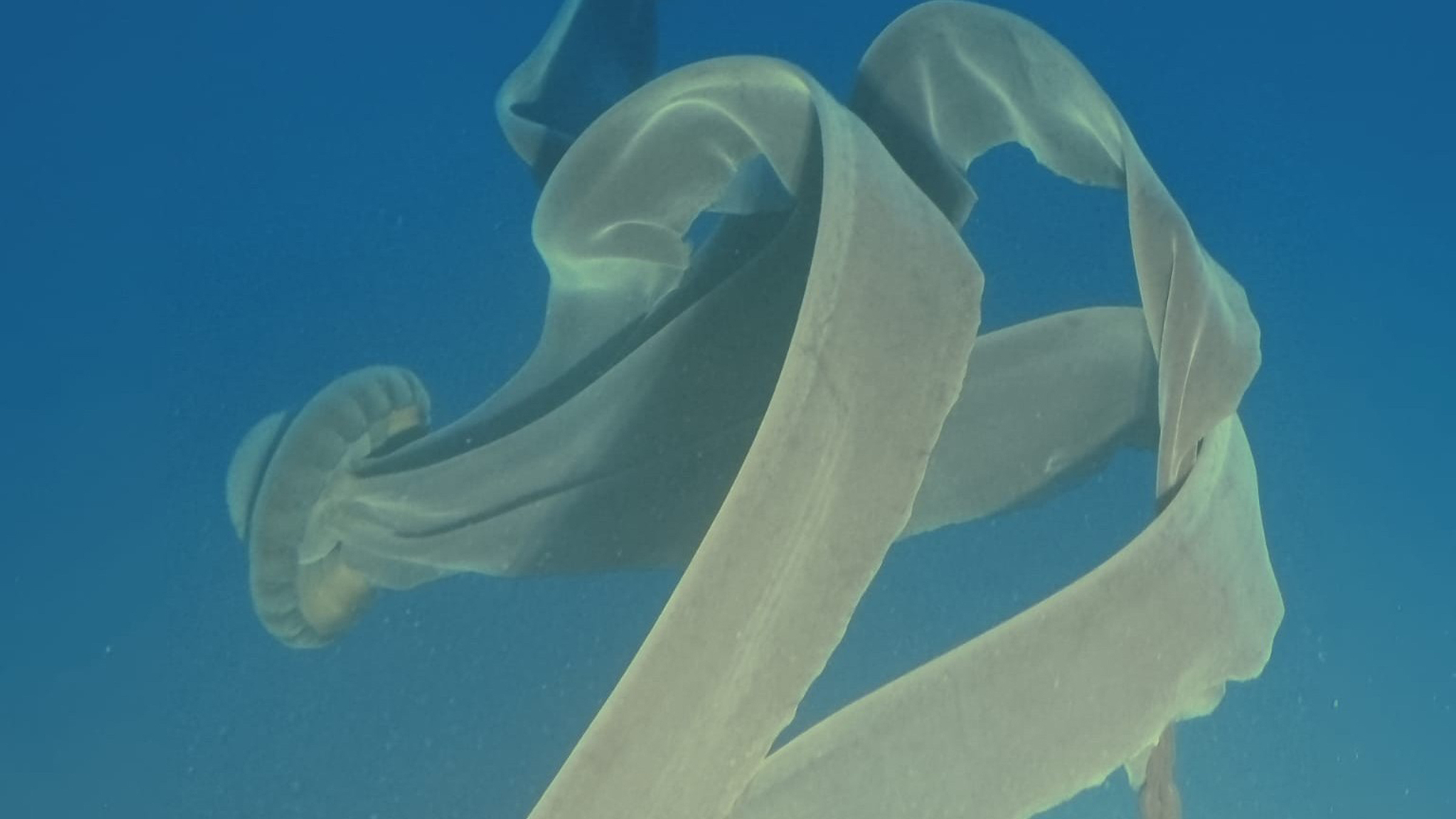

Why it's awesome: Earth's oceans are home to many secretive and unusual creatures that humans rarely see — including giant phantom jellies. These elusive deep-sea creatures have a 3.3-foot-wide (1 meter) bell and four ribbon-like arms that grow up to 33 feet (10 m) long, making them among the largest invertebrate predators in the ocean.

The first giant phantom jelly specimen was collected in 1899 and described in 1910. The species has only been spotted around 120 times since. This is because these jellies generally live in deep waters, down as far as 22,000 feet (6,700 m) below the surface.

They have compressible, squashable bodies, which help them to survive the incredibly high pressures they experience at these depths.

In 2022, researchers observed giant phantom jellies on three separate occasions during submersible expeditions in Antarctica, with videos and images showing the creatures swimming at relatively shallow depths of between 260 and 920 feet (80 to 280 m). In a study reporting the sightings, researchers said it's likely the jellies live closer to the surface in high southern latitudes because seasonal variations in sunlight may drive prey closer to the surface.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Unlike other jellyfish, giant phantom jellies don't have stinging tentacles to catch prey. Instead, they wrap their arms around their food — usually plankton or small fish — and hoist them into their mouths.

Related: Newly discovered jellyfish is a 24-eyed weirdo related to the world's most venomous marine creature

Giant phantom jellies also differ from other jellyfish by being viviparous, meaning they give birth to live young. The young develop inside the mother before detaching from inside the hood and swimming out of their mother's mouth.

When there is visible light, giant phantom jellies emit a slight orange-red light via bioluminescence — meaning they produce light through natural chemical reactions. It's not known exactly why they glow, but researchers believe it could be to communicate, confuse predators, lure prey or attract potential mates. However, because these jellies live in the deep ocean — where red light cannot penetrate very far — their glow is very faint, which likely helps to keep them hidden.

These jellyfish are solo explorers, but they also appear to help to protect smaller sea creatures. During an expedition in the Gulf of California, researchers from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute spotted small fish, pelagic brotula (Thalassobathia pelagica) sheltering underneath a giant phantom jelly. In return, the fish aided the jelly by removing parasites.

Lydia Smith is a health and science journalist who works for U.K. and U.S. publications. She is studying for an MSc in psychology at the University of Glasgow and has an MA in English literature from King's College London.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus