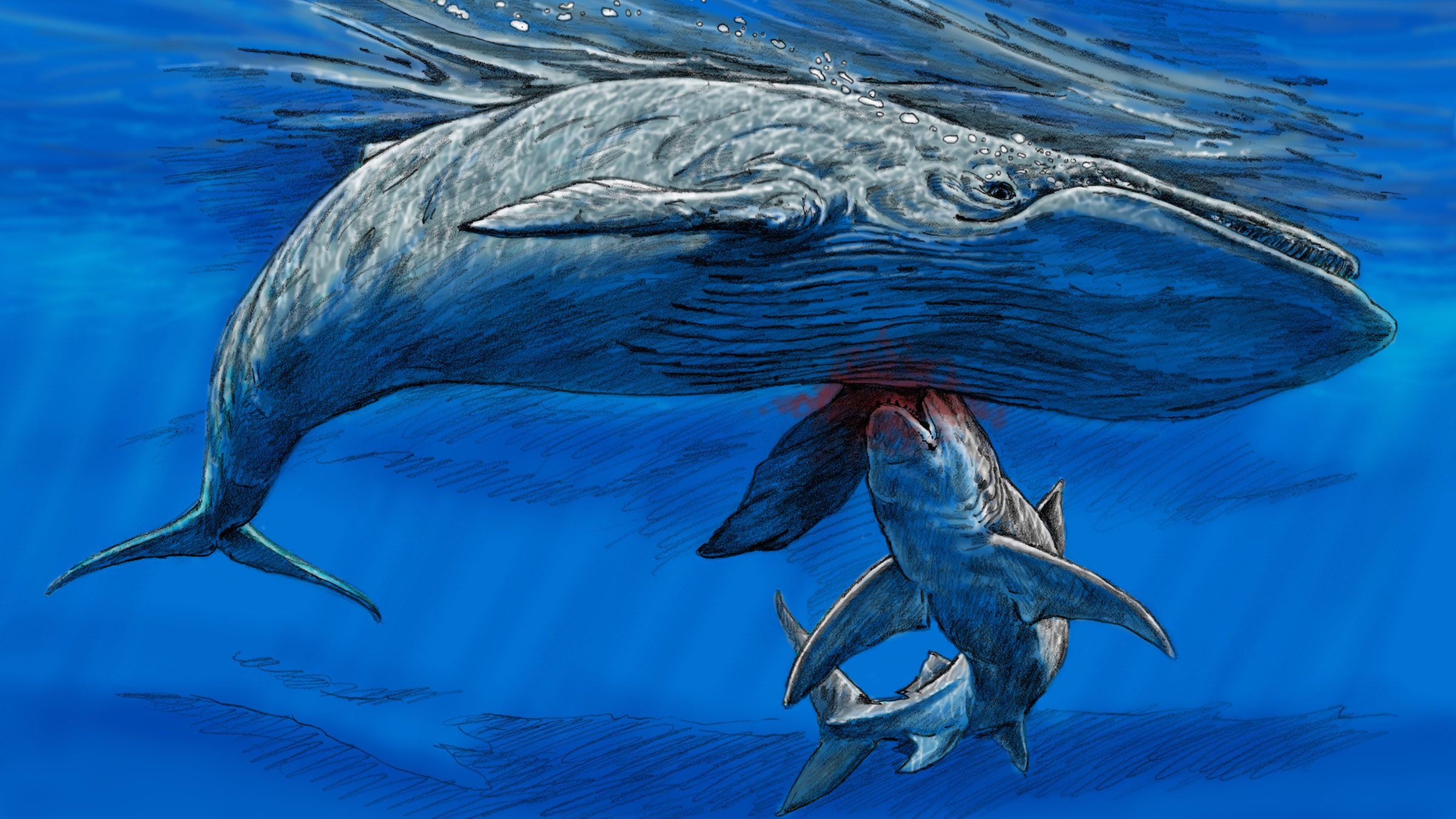

Giant shark, possibly a megalodon, feasted on this whale 15 million years ago

The shark, thrashing its head, sunk its teeth into the whale.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A ravenous shark — possibly a megalodon (Otodus megalodon), the largest shark that ever lived — sunk its teeth into a baleen whale up to 15 million years ago in what is now Maryland, according to a new study of the whale's flipper bone.

However, the whale was probably already dead and floating at the water's surface, an analysis of the bite marks on its radius, or flipper bone, indicated. So megalodon or some other giant shark was likely scavenging the blubbery beast, biting into the whale's flipper and thrashing its head back and forth to tear off its meal.

"These bite-shake traces consisting of shallow, thin arching gouges on the radius likely indicate scavenging rather than active predation," study lead researcher Stephen Godfrey, curator of paleontology at the Calvert Marine Museum in Solomons, Maryland, told Live Science in an email.

Related: Photos: These animals used to be giants

Maryland fossil collector William (Douggie) Douglass discovered the whale bone, which dates to the Miocene epoch (23 million to 5.3 million years ago), on the beach near the naturally eroding Calvert Cliffs, an area known for its extraordinary marine fossils. During the Miocene, the Atlantic Ocean intermittently flooded what is now Maryland's Chesapeake area. The fossil-filled marine sediments that now make up the cliffs were laid down between 20 million and 9 million years ago, Godfrey said.

Usually, Douglass sells his fossils along the side of the highway, but in this case, he donated the whale bone to the Calvert Marine Museum. "He noticed the shark-bite traces and brought it to me at the museum, suspecting that I would have an interest in this unusual find," Godfrey said.

The nearly 11-inch-long (27.5 centimeters) flipper bone is somewhat flattened and has a gently curved shape — features that are indicative of a baleen, or filter-feeding, whale. The bone is most similar to the extinct local whale Diorocetus hiatus, noted Godfrey, who did the research with former paleontology summer intern Annie Lowry.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found shark bite-and-shake marks on both sides of the whale's flipper bone.

"The shark would have clenched down on the flipper firmly and then shaken its head vigorously in an attempt to cut through the bone (unsuccessfully) or to simply remove flesh," Godfrey wrote in the email. "After it had removed some flesh, it re-bit the flipper to remove more flesh."

Luckily, the whale was likely dead and floating at the water's surface when the shark attacked it.

"When a whale dies, it inverts and floats at the surface of the water due to the buildup of abdominal gases from decomposition," Godfrey said. Scavenging sharks frequently feed at the water's surface, sometimes lifting their heads out of the ocean, so the whale's flipper would have been an easy target for the big fish.

Like other trace fossils — evidence of animals, rather than the animals themselves — this one was given a scientific name: Linichnus bromleyi, Godfrey said.

So, which shark scavenged the whale? It's hard to say, Godfrey said.

Suspects include (in alphabetical order): Alopias grandis, Alopias palatasi, Carcharhinus, Carcharodon hastalis, Galeocerdo aduncus, Hemipristis serra, a juvenile O. megalodon, Physogaleus contortus and Sphyrna laevissima.

The bite marks don't clearly show whether the shark had serrated teeth, but if the marks were made by a non-serrated tooth, then the "most likely candidate would be Carcharodon hastalis — the ancestor of the living great white shark," Godfrey said.

The research, which was published online Oct. 24 in the journal Carnets Geol., will be presented online Friday (Nov. 5) at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology's annual conference, which is virtual this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus