There's a Lost Continent Hiding Beneath Europe

"Greater Adria" existed hundreds of millions of years ago after it broke off from the supercontinent Gondwana.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

There's a lost continent hidden below southern Europe. And researchers have created the most detailed reconstruction of it yet.

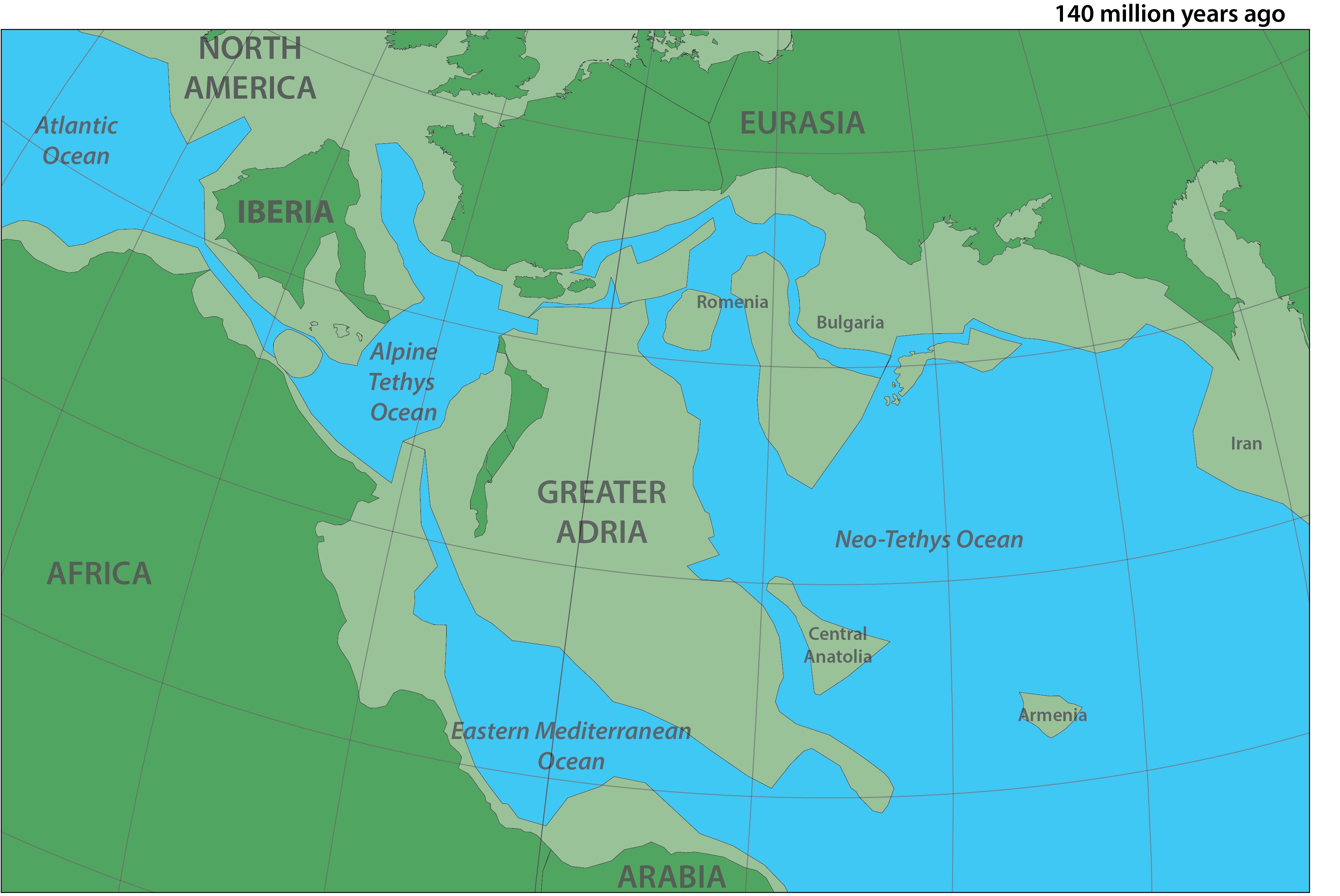

The lost continent "Greater Adria" emerged about 240 million years ago, after it broke off from Gondwana, a southern supercontinent made up of Africa, Antarctica, South America, Australia and other major landmasses, as Science magazine reported.

Greater Adria was large, extending from what is now the Alps all the way to Iran, but not all of it was above the water. That means it was likely a string of islands or archipelagos, said lead author Douwe van Hinsbergen, the chair in global tectonics and paleogeography in the Department of Earth Sciences at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. It would have been a "good scuba diving region."

Related: In Images: How North America Grew As a Continent

Hinsbergen and his team spent a decade collecting and analyzing rocks that used to be part of this ancient continent. The mountain belts where these Greater Adrian rocks are found span about 30 different countries, Hinsbergen told Live Science. "Every country has their own geological survey and their own maps and their own stories and their own continents," he said. With this study, "we brought that all together in one big picture."

Earth is covered in large tectonic plates that move relative to each other. Greater Adria belonged to the African tectonic plate (but was not a part of the African continent, since there was an ocean between them), which was slowly sliding beneath the Eurasian tectonic plate, in what is now southern Europe.

Around 100 million to 120 million years ago, Greater Adria smashed into Europe and began diving beneath it — but some of the rocks were too light and so did not sink into Earth's mantle. Instead, they were "scraped off" — in a way that's similar to what happens when a person puts their arm under a table and then slowly moves it underneath: The sleeve get crumpled up, he said. This crumpling formed mountain chains such as the Alps. It also kept these ancient rocks locked in place, where geologists could find them.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hinsbergen and his team looked at the orientation of tiny, magnetic minerals formed by primeval bacteria in these rocks. The bacteria make these magnetic particles in order to orient themselves with the Earth's magnetic field. When the bacteria die, the magnetic minerals are left behind in the sediment, Hinsbergen said.

With time the sediment around them turns into rock, freezing them in the orientation they were in hundreds of millions of years ago. Hinsbergen and his team found that in many of these regions, the rocks had undergone very large rotations.

What's more, Hinsbergen's team pieced together large rocks that used to belong together, such as in a belt of volcanoes or in a big coral reef. Moving faults scattered the rocks "like pieces of a broken plate," he said.

It's like a big jigsaw puzzle, Hinsbergen said. "All the bits and pieces are jumbled up and I spent the last 10 years making the puzzle again." From there, they used software to create detailed maps of the ancient continent and confirmed that it moved northward while twisting slightly, before colliding with Europe.

After many years working in the Mediterranean region, Hinsbergen has now moved on to reconstruct the lost plates in the Pacific Ocean. "But I'll probably return — probably in 5 or 10 years from now when a whole bunch of young students will demonstrate that parts are wrong," Hinsbergan said. "Then I'll come back and see if I can fix it."

The findings were published Sept. 3 in the journal Gondwana Research.

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

- Photo Timeline: How the Earth Formed

- Photos: The World's Weirdest Geological Formations

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus