Burial of infant 'Neve' could be oldest of its kind in Europe

10,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers buried this infant girl.

Archaeologists in Italy have unearthed the earliest known female infant burial in Europe, the 10,000-year-old grave of a newborn baby. The young girl, who researchers have nicknamed "Neve," was buried with a rich array of grave goods, such as shell beads and pendants.

The discovery sheds light on the cultural beliefs and social status of post-ice age humans in Europe — a period in human prehistory from which recorded burials are remarkably rare. The care given to the infant upon her burial suggests that even the tiniest members of this ancient society were considered "people," the researchers argue.

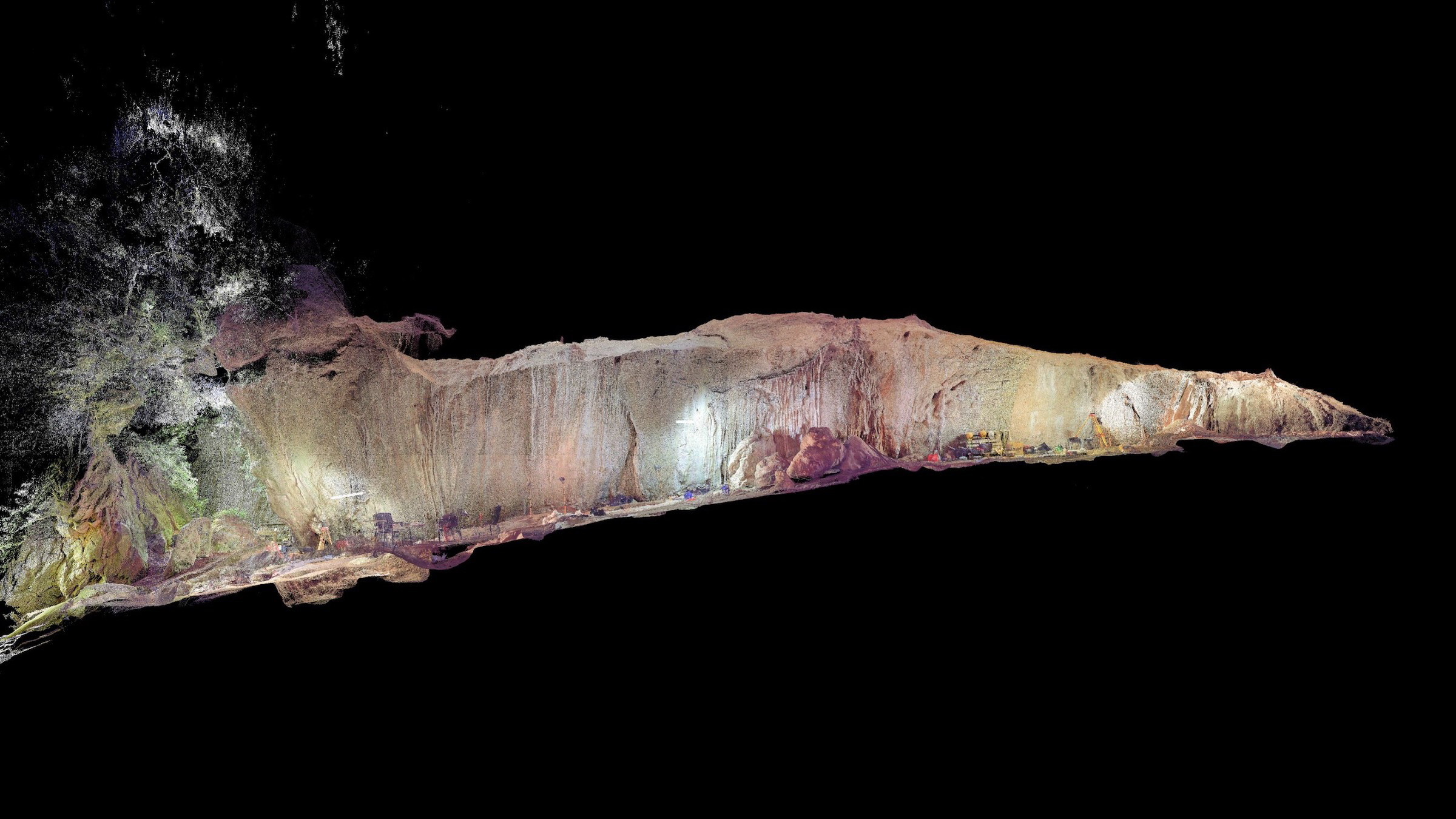

Archaeologists discovered the burial in 2017 during excavations at a cave site known as Arma Veirana in the foothills of the Ligurian Alps of northwestern Italy. Previous excavations at the cave have unearthed artifacts associated with Neanderthals, who occupied the cave 50,000 years ago. So the discovery of the child burial, which was 40,000 years younger, was a surprise.

Related: Back to the Stone Age: 17 key milestones in Paleolithic life

This time period, known as the Mesolithic, occurred at the end of the last great ice age in Europe, before the widespread adoption of agriculture. Humans at that time lived in hunting and gathering groups, and roamed the plains of Europe using skins for clothes and wood and stone for tools.

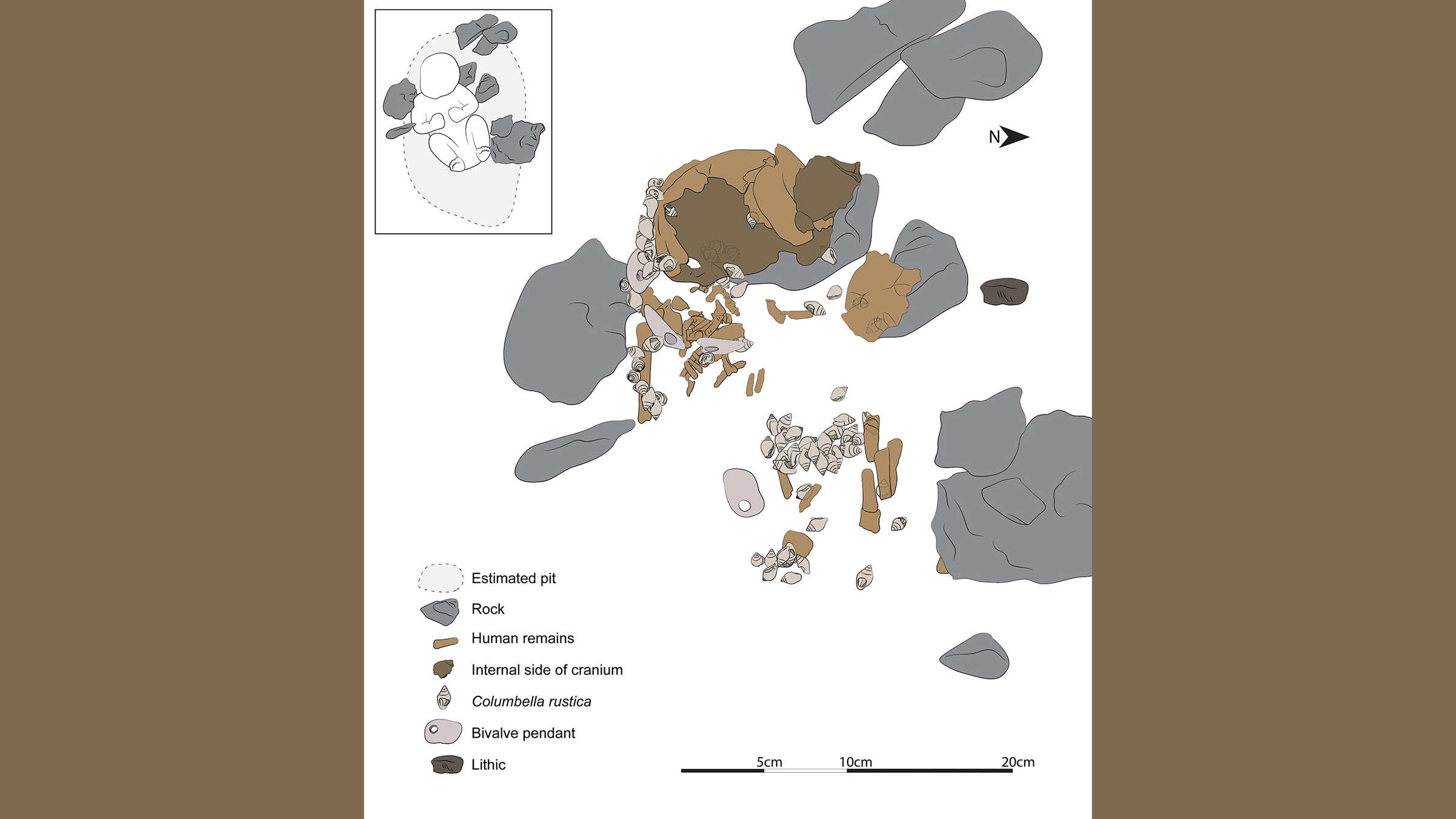

The excavators unearthed the burial in the deeper recesses of the cave. They had excavated near the cave's mouth during earlier excavations and had moved deeper into the cave to learn more about its occupation history and geologic layers. The team soon began to uncover perforated shell beads that dated to the post-Neanderthal period. A few days later, one of the excavators uncovered the fragment of a human skull. As they continued to dig, they found a deliberately interred human child.

Subsequent DNA analyses revealed that the child belonged to a lineage of European women known as the U5b2b haplogroup. The U5 haplogroup is the predominant maternal lineage found in European Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, and it likely originated between 17,000 and 12,000 years ago. Other analyses showed that she died some 40 to 50 days after birth and that she had experienced physiological stress that disrupted the growth of her at two separate time points — 47 days and 28 days before her birth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

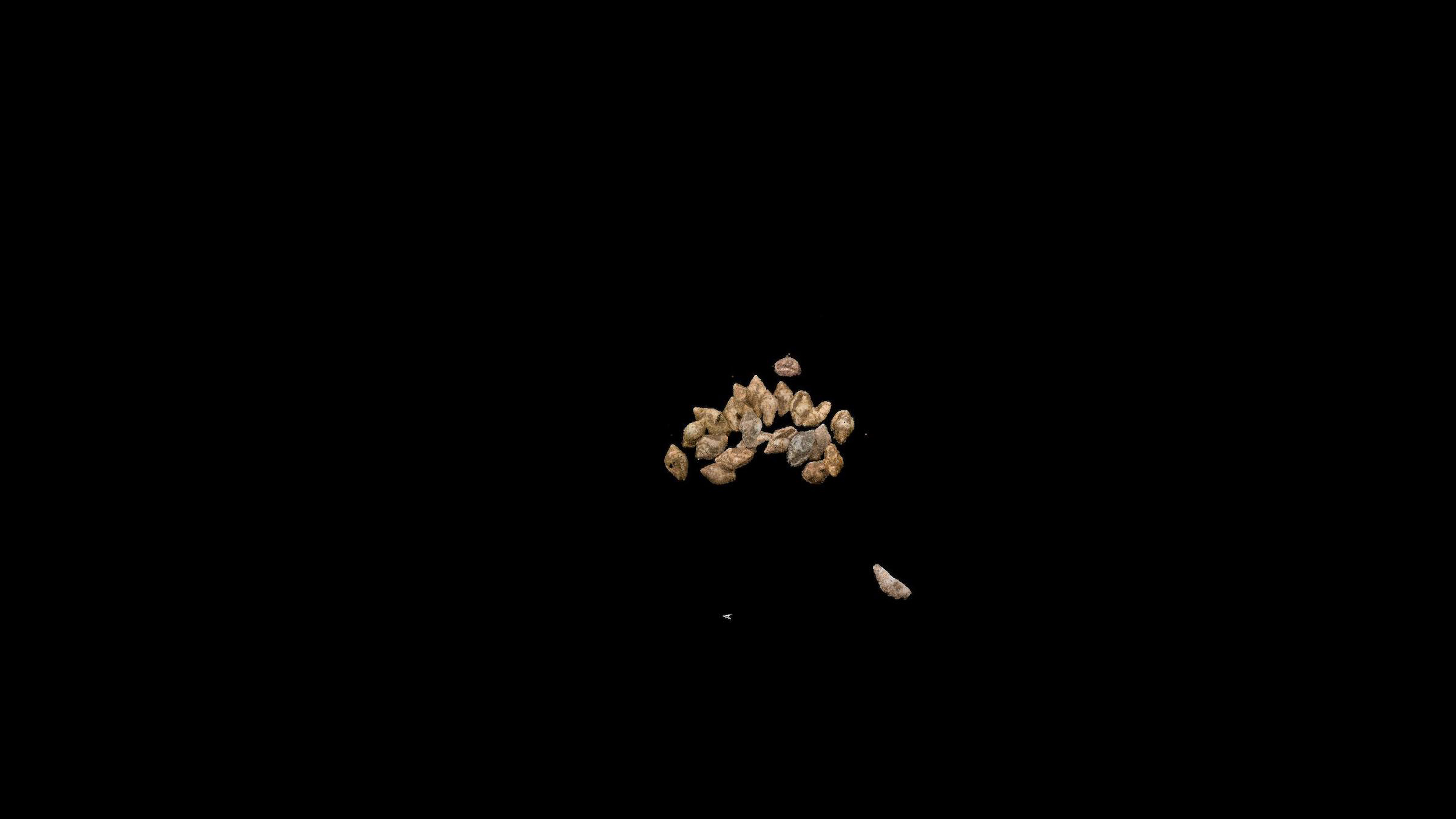

The find is especially important because it sheds light on the cultural beliefs of those living during this little-known period. The child was buried with over 60 perforated shell beads, 4 shell pendants and the talon of an eagle-owl. The beads required great care to make and maintain, suggesting that the ornaments were passed down to the child from group members. It also indicates that even the youngest members of the hunting and gathering group were invested with personhood and thought to have an individual self, moral agency and eligibility for group membership, the researchers suggested.

"The Mesolithic is particularly interesting," study co-author Carey Orr, a paleoanthropologist and anatomist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, said in a statement. "It followed the end of the final ice age and represents the last period in Europe when hunting and gathering was the primary way of making a living. So, it's a really important time period for understanding human prehistory."

The burial was described in a study published Dec. 14 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Garlinghouse is a journalist specializing in general science stories. He has a Ph.D. in archaeology from the University of California, Davis, and was a practicing archaeologist prior to receiving his MA in science journalism from the University of California, Santa Cruz. His work has appeared in an eclectic array of print and online publications, including the Monterey Herald, the San Jose Mercury News, History Today, Sapiens.org, Science.com, Current World Archaeology and many others. He is also a novelist whose first novel Mind Fields, was recently published by Open-Books.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus