8,000-Year-Old Heads on Stakes Found in Mysterious Underwater Grave

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The discovery of a burial containing 8,000-year-old battered human skulls, including two that still have pointed wooden stakes through them, has left archaeologists baffled, according to a new study from Sweden.

It's hard to make heads or tails of the finding: During the Stone Age, the grave would have sat at the bottom of a small lake, meaning that the skulls would have been placed underwater. Moreover, of the remains of at least 11 adults placed on top of the grave, only one had a jawbone, the researchers said.

The burial did contain other jawbones, although none of them, except for an infant's, were human. While excavating the site, archaeologists found various animal bones, including dismembered jawbones and arms and legs (all from the right side of the body), said study co-lead researcher Fredrik Hallgren, an archaeologist at the Cultural Heritage Foundation in Västerås, Sweden. [See Images from the Mysterious Burial Found in Sweden]

"Here, we have an example of a very complex ritual, which is very structured," Hallgren told Live Science. "Even though we can't decipher the meaning of the ritual, we can still appreciate the complexity of it, of these prehistoric hunter-gatherers."

Traumatic blows

The ancient burial site holds 11 adults (mostly their skulls and a few bones) and nearly the entire skeleton of an infant, who was likely stillborn or died shortly after birth. It was difficult to identify the sex of some, but at least three of the adults were female and six or seven were males, the researchers said.

Seven of the adults, including two of the females, showed signs of "blunt-force trauma" on their skulls, the researchers wrote in the study. But this trauma didn't kill them, at least not immediately, because all of the skulls showed signs of healing, Hallgren said.

"Somebody gave them love and care after this [trauma] and healed them back to life again," he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An analysis shed some light on the ancient carnage: The majority of the trauma happened above the hat line, which "is an indication that this trauma is the result of violence between humans," Hallgren said. What's more, the men tended to have trauma on top of and on the front of their heads, while the women's injuries were located on the backs of their heads, the researchers said.

Even more astounding were the wooden stakes found in two of the skulls. One stake had broken, but the other was long, about 1.5 feet (47 centimeters) in length, and both likely served as handles or mounts for the skulls, Hallgren said. They found a piece of brain tissue inside the skull with the broken stake through it.

The fact that the 8,000-year-old brain didn't decompose suggests that the individual was placed in the water soon after death, Hallgren said. However, some of the other skulls may have been placed there long after death, as it's possible the site may have served as a second burial for them, Hallgren said. [25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

Enigmatic structure

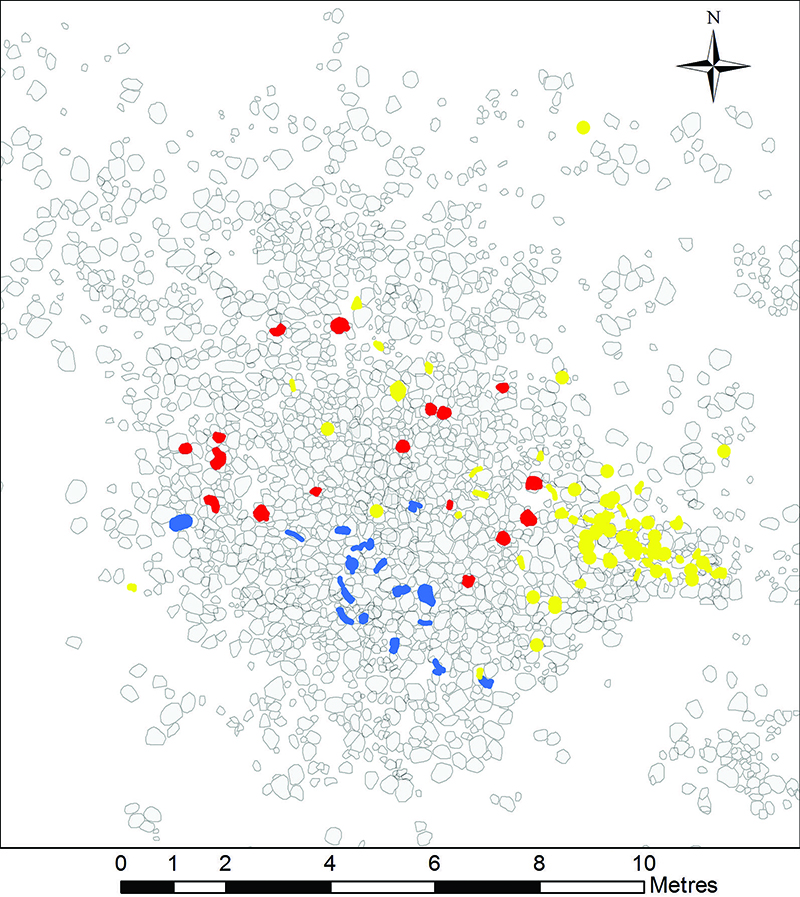

This strange burial site would have been hidden from view during the Stone Age, except for a few wooden stakes that may have poked above the water's edge, Hallgren said. Whoever made the grave began by tightly placing large stones and wooden stakes together at the lake's bottom, making a flat structure measuring about 39 feet by 46 feet (12 by 14 meters), meaning each side was about the length of a school bus.

The bones were placed on top of these stones in a particular order; archaeologists found the human remains in the center of the structure, brown bear bones on the southern part and, finally, big game animals, including wild boar, red deer, moose and roe deer, on the southeastern part of the stone packing.

"It's a very enigmatic structure," Hallgren said. "We really don't understand the reason why they did this and why they put it under water."

Though mysterious, the underwater burial had an upside: it preserved the remains for posterity. The bottom of the lake was a low-oxygen environment, meaning there wasn't much oxygen available for bone-decaying microorganisms, Hallgren said. In addition, limestone in the region's bedrock made the soil more alkaline (or basic), so the bones didn't leach away due to acid rain or acidic groundwater, Hallgren said.

Over time, the lake became overrun with reeds, and it turned into a bog. Eventually, a forest grew over the bog, but the area is still watery. Archaeologists were initially called to the area — located at the archaeological site of Kanaljorden, in eastern-central Sweden — to survey it for artifacts before the construction of a new railroad and bridge, Hallgren said. Once they found the strange burial, which was still located underwater, they immediately got to work, excavating from 2009 to 2013.

"The peat was still wet," Hallgren said. "In some parts of the site, we had to keep an electrical pump running to pump out the water that was running from the ground."

What happened?

It's anyone's guess what caused these ancient people so much trauma, and what prompted the unusual burial. It's possible the people were part of a stigmatized group — perhaps, for instance, they were slaves. But it was uncommon for hunter-gatherer cultures, which were often on the move, to own slaves, the researchers said.

Or maybe the people were victims of a raid from another hunter-gatherer group, and the unique burial was a way to honor them for their courage, the researchers said. [Photos: The Oldest Known Evidence of Warfare Unearthed]

"The people who were deposited like this in the lake, they weren't average people," Hallgren said, "but probably people who, after they died, had been selected to be included in this ritual because of who they were, because of things they experienced in life."

The discovery is "very interesting, but also very perplexing," said Mark Golitko, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Notre Dame, who was not involved in the study.

Golitko studies archaeological sites in Europe that have signs of ancient violence. "Most of the sites you can look at and get a rough sense of what's going on, but this is one of those where it's, like, I really don't know. It's a very strange site," Golitko told Live Science.

Between the trauma to the skulls and the strange burial, "There's clearly something ritual going on here," Golitko said. "What all that means, I don't think we'll ever know."

The study was published online today (Feb. 13) in the journal Antiquity.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus