The Falklands War: Margaret Thatcher's great victory

When British sovereign territory was invaded for the first time in a generation, everyone said it would be impossible to reclaim.

In 1982, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Argentine President General Leopoldo Galtieri had much in common. Both were fervently anti-Communist, both presided over nations in economic turmoil, and both were ruthless leaders prepared assert their power by going to war.

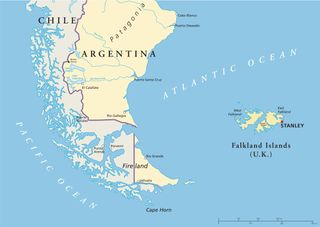

On April 2, 1982, Argentina sent a force of 600 soldiers to seize control of the tiny British-held islands off the country's coast, according to the Imperial War Museums. In the pre-dawn hours, two Argentine Navy vessels crept up on the coast of East Falkland, close to the capital city of Port Stanley, and unleashed an armada of landing craft into the choppy waters of the South Atlantic. Equipped with armored personnel carriers, heavy machine guns, mortars and recoilless rifles, the invasion force swept ashore unchallenged and rushed inland toward the capital.

Related: Read a FREE issue of All About History magazine

At the start, fewer than 100 Royal Marines stationed on East Falkland were all that stood in the way of Argentina realizing a dream that dated back to its birth as an independent nation 170 years earlier. To take back the Falkland Islands, known to the Argentines as Islas Malvinas, which they considered rightfully theirs, and to finally boot out the region's last remaining colonial bullies was more than just a matter of national pride — it was the fulfilment of a long-awaited destiny.

The lightly-armed British soldiers were outnumbered, and Argentinian commanders predicted their opponents would surrender without a fight. But the Brits held out for three hours, inflicting casualties and kills without suffering any themselves.

Nonetheless, as news of the invasion reached Buenos Aires, locals swept out onto the streets to show their support for the Galtieri-led junta — their authoritarian, military-led government. A 250,000-strong crowd appeared in the heart of the capital chanting their approval where just days before they gathered to howl in protest against rocketing inflation, unemployment and the regime's brutality, according to a review published by the Center for Contemporary Conflict.

Britain's reaction

In London, the mood couldn't have been more different. While not everyone could be sure where the Falkland Islands were (off the coast of Scotland was the joke doing the rounds) the British establishment quickly talked itself into a state of righteous indignation. British sovereign territory had been invaded, the country's honor insulted and the lack of respect shown by the nation of Argentina was indicative of just how far Britain's national standing had fallen.

The popularity of the Thatcher government in the spring of 1982 was at an all-time low. Spiraling unemployment and inner-city riots, coupled with her perceived lack of compassion had rendered Thatcher an electoral liability. Documents declassified decades after the war revealed that Thatcher described the invasion as the worst moment of her life, the BBC reported.

Related: Margaret Thatcher: Why powerful women face more stress

The U.S. was Britain's biggest ally, but this was happening during the height of the Cold War, and America was far more concerned with containing communism than helping preserve British overseas interests. Galtieri may have been a brutal dictator, but in the eyes of the American government, he was anti-Communist and therefore, an important leader in South America. President Ronald Reagan swiftly dispatched Secretary of State Alexander Haig to London to explain the American perspective to the prime minister.

But when Haig arrived in London on April 8, 1982, he was too late. A British military task force had set sail for Argentina three days earlier, and as Haig would discover, Thatcher had no interest in asking them to return home.

Related: Cold War satellites tracked missiles and … marmots?

As the flotilla's flagship, the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes steamed out of Portsmouth on April 5. Television news footage showed rows of specialized military aircraft sitting proudly on the deck of the HMS Hermes' deck, rather than stored below as they typically would have been. This was Thatcher's way of broadcasting a message to the world: Britain wasn't messing around. As the ships departed, the public enthusiastically waved troops off with Union flags while military bands played Victorian marching tunes on the dockside. The spirit of jingoism was being reawakened as the British nation lined up behind its leader.

A diplomatic dead end

Thatcher's newly formed War Cabinet was essentially the prime minister's inner court — her most trusted political and military advisors. But it was Chief of the Defence Staff Admiral Terence Lewin who set the cabinet's agenda. By the time Haig arrived, the War Cabinet was entirely focused on the liberation of the Falkland Islands and the removal of the occupying army.

The Argentine junta, meanwhile, had even less intention of abandoning the islands than it did of compromising. Documents released in 2012 show just how far the U.S. was prepared to go in appeasing Galtieri, with minutes from a meeting on April 30 revealing the extent of Haig's exasperation with the regime. "Our proposals, in fact, are a camouflaged transfer of sovereignty," he told colleagues. "The Argentine foreign minister knows this, but the junta will not accept it."

Related: The outer-space treaty has been successful — but is it fit for the modern age?

As U.S. diplomat Jean Kirkpatrick later recalled of the Argentine position in a 1990 interview: "I don't think they understood what war was like. They didn't understand they were going to be defeated … and they didn't really understand that young Argentines and young Brits were going to die in this effort. There was a real Don Quixotesque sense of unreality about their attitude as I experienced it."

It was true. The junta's leaders may have worn flash uniforms and rows of medals, but few had been anywhere near a battlefield. The same was tragically true of the men they sent to do their fighting. As the task force edged closer, the Falklands began to fill up with thousands of young conscripts, many still teenagers. When hostilities started, there may have been 13,000 Argentinian troops on the islands, but they were up against the very best the British war machine had: Royal Marines, the Parachute Regiment, Ghurkas, the Scots and Welsh Guards, plus various special forces.

Battle highlights

When the battle for the Falklands began on May 1, the first clash was in the air. Despite being outnumbered, the British had the technological edge. Their newly acquired sea harriers, vertical take off/landing fighter jets, were armed with the latest sidewinder missile system, allowing pilot aces to shoot down four Argentinian planes on the first day alone.

But the Brits weren't to have all the wins. To control the skies, the carriers had to be protected at all costs. After sinking the Argentine Cruiser Belgrano on May 2, Britain suffered its first major loss. On May 4, in retaliation for the Belgrano, Argentine air forces attacked and sank the British destroyer HMS Sheffield, killing 20 British soldiers.

By mid-May the South Atlantic winter was kicking in and foul weather hampered the British air campaign. With time running out, and Thatcher ruling out the option of turning back, the Brits decided to launch the land invasion without air cover — a high-risk strategy. On May 18, the second wave of British ships arrived just off the Falklands. It included the landing force of marines and paratroopers who would spearhead the invasion under the command of Brigadier Julian Thompson.

Related: 'Vigorous' magnetic field oddity spotted over South Atlantic

In the early hours of May 21, Thompson's troops hit the beaches of San Carlos Bay on the northwest coast of East Falkland. Encountering little resistance, they made for the high ground and dug in. Below them, in the bay, the ships that brought them were unloading supplies when they were attacked by Argentine air forces. The attacks continued for four days and by the end of it eight ships had been hit and two sunk. But the worst was yet to come.

On May 25, Thompson's helicopters finally arrived in a cargo ship called the Atlantic Conveyor. As the ship approached San Carlos, Argentinian jets launched an attack and destroyed all but one of the helicopters, the BBC reported. In a very short amount of time, the British ground campaign was transformed and destined to be vastly different from the one commanders had envisaged. This most modern of wars would now be fought and won on foot.

As Argentine air assaults on British naval forces continued, British land forces were making headway. By June 1, with the arrival of an additional 5,000 troops, the British were planning their attack on Port Stanley, according to the Falklands War Military Wiki.

Argentina surrenders

The British advance was not without set-backs, and by the time the Argentinians surrendered on June 14, British casualties numbered over 1,000, with 258 dead. The Argentinians, on the other hand, suffered 649 dead and 1,600 wounded. Of the 1,820 Falklanders, just three had lost their lives.

Within days, Galtieri was swept from power and Argentina — rather than opting for Communism, as Reagan had feared — was on its way to reestablishing itself as a democracy.

The real winner, though, was Margaret Thatcher. Almost a year to the day after the end of hostilities, she was re-elected prime minister by a landslide off the back of the victory. What many military analysts had declared impossible — to launch a successful seaborne invasion of a target 8,000 miles away in hostile waters with no real prospect of resupply — had been achieved in just 74 days.

Additional resources:

- Find more photos and information about the Falklands War from Britain's National Army Museum.

- Watch footage of a tense aerial battle during the Falklands War, from the Smithsonian.

- Watch a short documentary about the land battles of the Falklands War, from British Army Documentaries.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

From the epic sieges of Medieval Europe to the daring dogfights of World War II, History of War takes you inside the minds of fighting men, under the bonnets of some of the world’s most devastating war machines, and high above the battlefield to see the broad sweep of conflict as it happened. Subscribe to the magazine here.