First Pressurized Plumbing of the New World Discovered

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A water feature found in the ancient Mayan city of Palenque, Mexico, is the earliest known example of plumbing with pressurized water in the New World, researchers suggest.

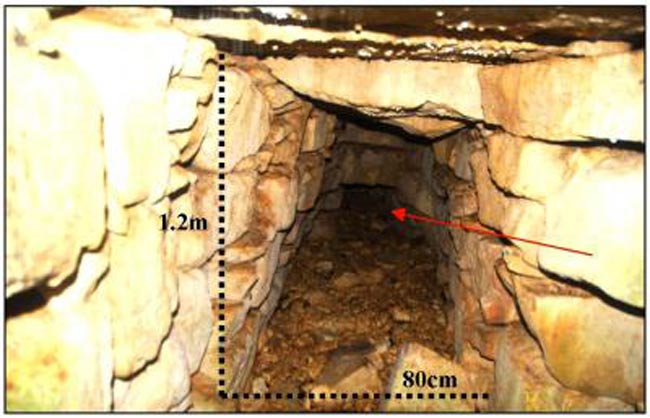

Found in the Piedras Bolas Aqueduct is a water spring-fed conduit located on steep terrain — a 20-foot (6-meter) drop from the entrance of the tunnel to the outlet about 200 feet (60 feet) downhill. The cross-section of the feature decreases from about 10 square feet (1 square meter) near the spring to about a half square foot where water emerges from a small opening. At the outlet, the pressure exerted could have moved the water upwards of 20 feet.

"The experience the Maya at Palenque had in constructing aqueducts for diversion of water and preservation of urban space may have led to the creation of useful water pressure," said team member Kirk French of Penn State University.

The researchers aren't exactly sure what the water-pressure feature was used for, but speculation includes a public fountain or a wastewater disposal system.

Previously, researchers thought that water-pressure systems entered the New World with the arrival of the Spanish, but this finding shows that closed channel water pressure systems were already present.

Underground water features such as aqueducts are not unusual at Palenque. Because the Maya built the city in a constricted area inhabitants were unable to spread out. To make as much land available for living as possible, the Maya at Palenque routed streams beneath plazas via aqueducts.

The feature was first identified in 1999 in the Maya city in Chiapas, Mexico. The area was first occupied sometime near the year 100, grew to its largest size during the Classic Maya period 250 to 600, and was then abandoned around 800.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Piedras Bolas Aqueduct is partially collapsed so very little water currently flows from the outlet. French and his team member Christopher Duffy, also of Penn State, used simple hydraulic models to determine the potential water pressure achievable from the Aqueduct. They also found that Aqueduct would hold about 18,000 gallons (68,000 liters) of water if the outlet were controlled to store the water.

The results of the study are detailed in the May issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies.

- Top 10 Ancient Capitals

- Ancient Mayans Likely Had Fountains and Toilets

- 10 Events That Changed History

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus