Computers Get Better at Face Recognition

Face-recognition systems are more accurate at identifying a face created by blending several photos of the same person than if the software relied on a single snapshot, finds a new study.

Experts in homeland security, crime prevention and immigration and employment verification could use automatic face recognition systems to confirm photo identifications. But for a variety of reasons, including the variability of photos themselves, most systems are too unreliable.

For instance, the appearance of a person's face changes from photo to photo due to real-life changes such as aging and facial expressions, the angle of one's head, how far away the photo was taken, and the direction and type of lighting in a photo.

"The machines just can't handle that kind of variability," said co-author Rob Jenkins, a cognitive psychologist at the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

By merging several photos, the researchers found they could get rid of irrelevant features and boost computer recognition. Their work is detailed in the Jan. 25 issue of the journal Science.

Celebrity faces

The psychologists tested their theory using a publicly available Web site, MyHeritage.com.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Originally a strictly genealogy domain, the site now includes a celebrity look-alike feature. When you upload images of yourself, for instance, face recognition software called FaceVACS scans through more than 30,000 celebrity photos to find the one that most resembles your photo.

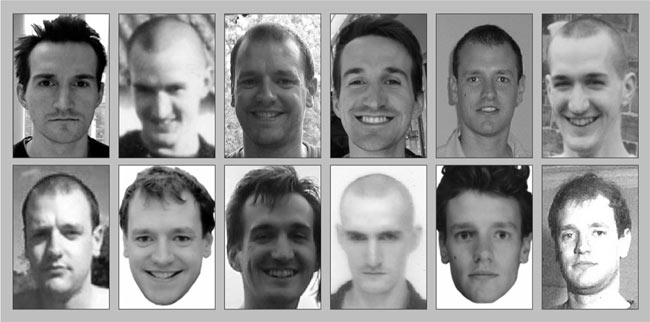

Instead of personal photos, Jenkins and Glasgow colleague A. Mike Burton submitted about 460 images of 25 male celebrities taken from a separate image database. When the images were uploaded separately, the recognition software was accurate 54 percent of the time.

Then, the researchers used a computer program to average about 20 images of each of the male celebrities, resulting in a composite image for each celebrity. The performance of FaceVACS shot up to 100 percent recognition for the composite-type images.

True identity

The image-averaging process is one the researchers say our brains might use to assimilate actual mental pictures of familiar faces. Prior research by Jenkins and his colleagues revealed that we are good at recognizing familiar faces in sets of photos but lousy sleuths when it comes to photos of faces we've never seen before in person.

“As humans, we are amazingly good at recognizing people we know, but we are actually very bad at matching someone we don't know to their photo," Burton said.

With familiar faces, our brains likely average together a slew of mental pictures collected over time, forming a true image of that person.

"In doing that, you wash away all the differences, lighting and pose, all those variations that don't tell you anything about who the person is," Jenkins told LiveScience. "You get rid of all that and what you're left with is the essence of that person's face."

In the long-term, the researchers envision a day when machines will rival humans in recognizing familiar faces in photos.

"What we're excited about is the prospect of getting machines to be as good as a familiar human is," Jenkins said, "so it would be a bit like everyone who goes through this automatic system would be friends and family, that level of facility with processing the face."

- Video: How Face Recognition Works

- Top 10 Technologies That Will Transform Your Life

- Great Inventions: Quiz Yourself

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.