Tropical Deforestation Would Alter Storm Paths, Reduce U.S. Rainfall

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Rainfall in parts of the United States would be reduced significantly by total deforestation in other parts of the world as the paths of storms are altered, new research shows.

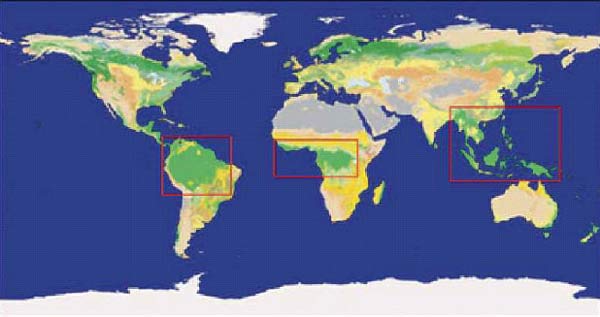

The study, led by researchers at Duke University using a NASA computer model, is among the first to reveal potential global effects of localized changes in the land. Among the findings:

- Deforestation in the Amazon region of South America would reduce rainfall in Texas by 25 percent from March to September.

- Deforestation in Central Africa would affect precipitation in the U.S. Midwest.

- Deforestation in Southeast Asia would alter rainfall in China and the Balkan Peninsula.

The scientists note, however, that the rainfall changes would primarily occur in certain seasons and that the combination of deforestation in these areas enhances rain in one region while reducing it in another. The total amount of rain that falls on Earth would not change, the computer modeling suggests.

Deforestation of Central Africa, for example, would cause a significant precipitation decrease in the lower U.S. Midwest during the spring and summer and in the upper U.S. Midwest in winter and spring. And the conversion of forests to shrub and grass in all three tropical regions studied would considerably enhance rainfall in the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula and eastern Africa, by up to 50 percent in some locales.

"Our study carried somewhat surprising results, showing that although the major impact of deforestation on precipitation is found in and near the deforested regions, it also has a strong influence on rainfall in the mid and even high latitudes," said Roni Avissar, lead author of the study, which was published earlier this year in the Journal of Hydrometeorology. The results were announced recently by NASA.

Rainforests are self-propagating in the sense that the moisture they hold and the temperatures they maintain help drive the very storms that keep them wet. The potential shifts detailed in the new research are driven by altered patterns of heat distribution in the atmosphere.

"Associated changes in air pressure distribution shift the typical global circulation patterns, sending storm systems off their typical paths," Avissar said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

There are other examples of regional climate changes having global effects.

Hurricane experts have long known that rainfall in the Sahel region of African affects the formation of hurricanes in the Atlantic, ultimately contributing to how many deadly storms hit the United States. El Nino, in the Pacific, also plays a role in Atlantic hurricane formation.

A study earlier this year found that when the African Congo Basin floods, the Amazon basin experiences a drought. And yet another result this year showed, surprisingly, that even the climates of the northern and southern hemispheres are linked.

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus