Mind Wandering May Lead to a Bad Mood

For the sake of your own happiness, don't let your mind wander while reading this article. Setting the mind adrift from the here and now may lead to a worse mood regardless of whether the daydreams or thoughts are pleasant ones, researchers say.

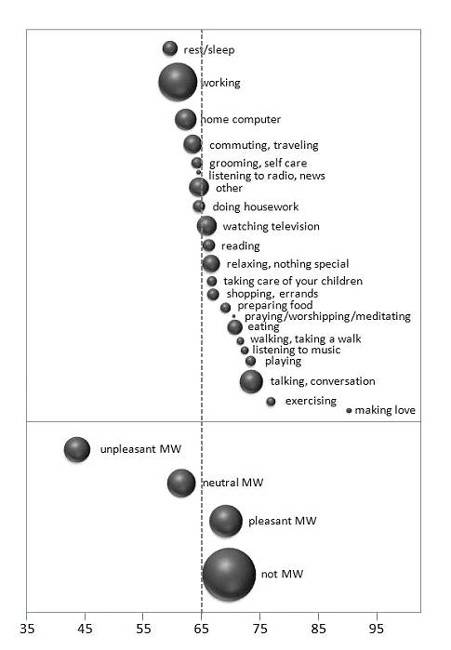

In fact, a wandering mind had a bigger influence on happiness than any other activity a person happened to be doing, according to their new study. Such findings confirm many philosophical and religious traditions, which teach about finding happiness by living in the moment, and train practitioners to resist mind wandering.

Humans have made good use of mind wandering to reflect upon the past or plan for the future, as well as to learn and to reason. But the study also showed that it comes with a powerful emotional cost, despite mind wandering appearing to be the brain's default mode of operation.

"We do hypothesize that it's a cause [for unhappiness]," said Matthew Killingsworth, a doctoral student in psychology at Harvard University and lead author on the study detailed in the Nov. 11 issue of the journal Science.

Follow the thoughts

Killingsworth and Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert tracked the happiness levels of iPhone users by asking participants about their happiness at random times. Participants rated their happiness on a scale of 0 to 100 and included what they were doing, and whether their mind was wandering beyond the task at hand. (Yes, there is an app for that experiment.)

People's minds wandered almost 47 percent of the time, and were more likely to think about pleasant topics than unpleasant or neutral ones. Yet thinking pleasant thoughts made people no happier than focusing on what they were doing – and unhappiness spiked when thinking neutral or unpleasant thoughts.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Such mind wandering appeared to cause unhappiness even when people were doing the least enjoyable activities, such as daily work. A time-lag analysis suggested that mind wandering caused foul moods rather than the other way around.

Another surprise: Whatever people were doing had only a mild impact on whether their minds wandered, and almost no impact on the pleasantness of the topics they chose to think about. Mind wandering took up at least 30 percent of the time during almost every activity, including playing, exercising, praying and taking care of the kids.

So what was the only exception? Apparently people focus most intensely on making love.

"[Making love] was 10 percent [for mind wandering], which was the lowest," Killingsworth said in an e-mail. "The highest was 'grooming, self care' at 65 percent."

Get your tracking on

The use of the smartphone app allowed the researchers to essentially track thousands of people's emotions in real-time as they went about their daily business – a huge advantage over limited lab studies. Each app query only reached iPhone users during their preferred waking hours, and took place randomly throughout the day.

The study's data included 2,250 adults with a mean age of 34 years. Almost 59 percent of participants are male, and 74 percent live in the United States. The average compliance in responding to each app query was a respectable 83 percent.

But the overall database already has almost a quarter of a million samples from 5,000 people. They hail from 83 different countries, range in age from 18 to 88, and collectively represent every one of the 86 major occupations or careers across the globe.

Killingsworth and Gilbert plan to continue sifting through the data, but chose to avoid spilling the beans for now.

"There are a variety of analyses we will do, but I don't have much to say on this point," Killingsworth said.

Anyone interested in sharing their current emotional status can find the iPhone app at trackyourhappiness.org.

- 7 Ways the Mind and Body Change with Age

- Happiness is Being Old, Male and Republican

- 10 Ways to Keep Your Mind Sharp