Brains Hard-Wired to Connect with Friends

Our brains seem to be hard-wired to identify and "get" our friends, a phenomenon that likely evolved to help ensure the survival of such a social species, research suggests.

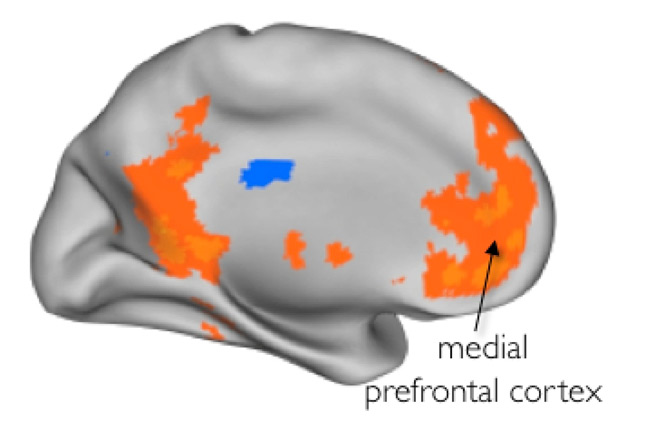

The brain-imaging study showed that increased activity in a network of brain regions took place when participants viewed pictures of themselves and thought about themselves as well as when they thought about friends (regardless of their similarities to each other).

Previous studies have suggested whether another person is similar to you, for instance in their beliefs, is an important dimension in our social world and played a role in humans' survival. "The theory is that we can only understand the minds ofother people to the extent that we view them as similar enough to us," said graduate student Fenna Krienen, who along with Randy Buckner, both of Harvard University, led the current study.

The team figured closeness might also play a role. "Maybe closeness would also be an important dimension to explore, because we are a social species, we may have evolved with a need to recognize and respond differently to people who are part of our social alliance, part of our clan," Krienen told LiveScience.

To find out, the researchers imaged brain activity of 32 participants as they judged how well lists of adjectives described their personalities as well as that of former President George W. Bush. This test revealed which brain regions are linked to personal, "self" information.

In three other experiments, a total of 66 different participants provided personality information about themselves and two friends — one friend who they believed had similar preferences and one believed to be dissimilar. That information was also used to create fictitious biographies of two "strangers" for other participants.

Then, while in a brain scanner, the participants played a game in which they predicted how another person would answer a question. For example, "Would a friend (or stranger) prefer an aisle or window seat on a flight?"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When answering questions about friends, both similar and dissimilar, the participants showed increased activity in the brain's medial prefrontal cortex and associated regions.

"It was interesting to us, because the same network that was active when people saw pictures of themselves was also highly active when they answered questions about their friends," Krienen said. "The strangers didn't activate that network nearly to the extent that the friends did. It seems to have to do with whether those people are socially close or self-relevant."

The medial prefrontal cortex and linked brain regions are associated with emotions and figuring out whether something or someone is positive or negative. The researchers think the brain network is tied to a person's understanding of the importance of another to oneself.

The research, detailed in the Oct. 13 issue of The Journal of Neuroscience, was funded by the National Institute on Aging, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Simons Foundation, the U.S. Department of Defense, and an Ashford Graduate Fellowshipin the Sciences.

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain

- 10 Things That Make Humans Special

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.