Mediterranean Shipwrecks Reveal Shift to Modern Shipbuilding

Three recently discovered shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea could give archaeologists new insights into the transition between medieval and modern shipbuilding.

The remains of the three craft – all dating from between 1450 and 1600 – were found in the straits between Turkey and the Greek island of Rhodes. One ship appears to be a large English merchant ship, while the other two are smaller – perhaps a patrol craft from Rhodes and a small trading boat that could have been Turkish, Italian or Greek.

Though the three shipwrecks were discovered near each other, they are not thought to be related, or to have foundered in the same event.

"The real import of those vessels were they just happen to be from that period when you're moving from those oared vessels that had guns on them to sailed vessels that had guns on them," said archaeologist Jeffrey G. Royal of the RPM Nautical Foundation in Key West, Fla. "We were fortunate to find several vessels that spoke to that era."

Treasures in the deep

To discover the shipwrecks the researchers used a combination of advanced technology, and persistence.

"We map the seafloor with a really intense sonar system that makes very accurate detailed maps of the seafloor," Royal told LiveScience. "Once we examine those maps we can tell anomalies that may be cultural remains versus geology."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

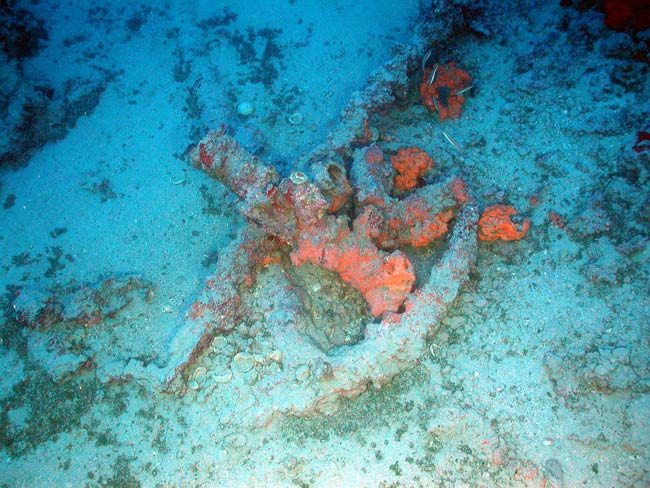

When sign of possible shipwrecks appeared, the researchers sent down automated robots with lamps and cameras and robotic arms, which confirmed there were remains.

Armed and dangerous

The team launched a full-scale investigation of the shipwreck trio. The scientists are interested in learning how shipbuilding evolved over time, and which changes in boat design had been applied during different eras.

Earlier ships were called galleys, and while they had sails, they were mainly powered by oars rowed by men. These were long and narrow, with cannons fixed forward and on their sides, Royal said.

Later came the sailing ships, which relied less on oars and more on harnessing the power of the wind. These were even longer and often had more cannons on their sides than front.

"The galleys would be quick over a short distance, and relatively maneuverable, but the sailing ships could go longer if the winds held up," Royal said. Galleys tended to slow down when manpower lagged and oarsmen got tired. The sailing ships also didn't have to maneuver quite as close to an enemy ship to fire at them, so they were more defensible.

The new discoveries seemed to be timed right to when this transition between boat types was taking place. The large British ship, thoughtto be a merchant trading ship, was armed with cannons, likely to protect against pirates who would aim to steal the valuable goods onboard. Both of the smaller vessels also had weapons.

This fact could reveal clues about what this area was like at the time.

"To find a high percentage of armed vessels from a narrow historical period clustered along the same stretch of Turkish coastline within the Rhodian Straits invites an analysis of the coastal geography and strategic context of those Straits, as well as the specific nature and assemblage of each site," Royal and co-researcher John M. McManamon of Loyola University Chicago wrote in a paper describing the finds in the September 2010 issue of the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology.

- Gallery: Shipwreck Alley's Sunken Treasures

- Test Your Knowledge on the Titanic Shipwreck

- 10 Events That Changed History