Ouch! The Alien Bite of the Moray Eel

Editor's Note: A news story about this research was published in September, 2007.

Moray eels, to my certain knowledge, will bite if provoked. They belong to a family of elongated bony fishes with an impressive dental battery (Muraenidae), and my right hand has distinct impressions to prove it.

My scars came from an encounter on the Great Barrier Reef with a hungry eel chomping at the chopped fish I was feeding to a group of groupers. The moray's bite beached me and left me with one good hand to gingerly eat my meals for the next month.

Not only do bony fishes lack hands or gripping forelimbs of any kind to reposition their meal, they are also deprived in the food-processing department by the total absence of a tongue. That leaves the fishes' jaws to do all of the work of converting whole prey into edible morsels. Some bony fish simply skip playing with their food and eat it whole; others, like bluefish, use cutting teeth to reduce the prey size, then swallow each piece whole. But the vast majority of bony fishes use a set of tools deep in their throat: a second pair of toothy jaws that can split, slice, tear, or crush food as it goes down the gullet.

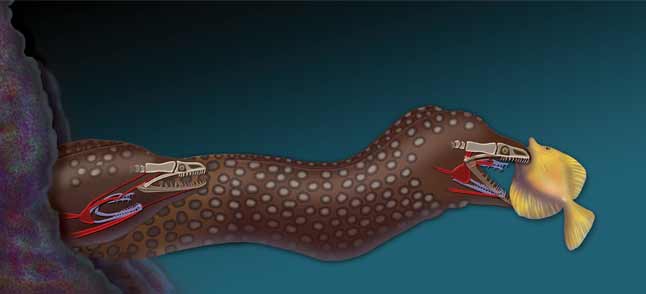

The back-of-the-throat choppers are called pharyngeal jaws, and they come in an astonishing array of sizes, shapes, and functions—all derived from gill arches, which hold in place the bright-red respiratory structures that lie behind the cheeks of most fishes. Pharyngeal jaws are equipped with their own set of teeth and move completely independently of the oral jaws. Still, the problem persists of how to move prey back from the mouth jaws to the throat set. Suction usually works. But moray eels, it turns out, have a way to use their pharyngeal jaws that's pretty shocking, right out of the movie Alien.

Rita Mehta, currently based at the University of California in Davis, is an expert on snakes' feeding behavior, so when she teamed up with fish biomechanist Peter Wainwright, also at Davis, she focused on the snakiest of fishes. For their body size, moray eels can eat extremely large prey, such as octopus, making Mehta think there might be an interesting story in how they manage to choke down such huge meals. Snakes have a mobile upper jaw which can ratchet from left to right, allowing a snake to “walk” its head down the length of its prey without ever releasing it from the grip of at least one side of the jaws. What about the eels?

Mehta started by using high-speed video to record adult reticulated morays (Muraena retifera) as they ate pieces of squid. The movies allowed her to really slow down the action, which showed that the food was hauled into the eel's mouth rather jerkily. That was hard to understand, but the mystery deepened when an eel ate with its mouth particularly wide open—and the camera caught a flash of something moving, something that seemed to come out of the throat and grab the prey. The pharyngeal jaws seemed unlikely candidates, since in moray eels they are set very far back in the body, well behind the back of the skull. Mehta set to finding out by using a fluoroscope, an X-ray machine that allows movies to be taken of moving bones. In a small glass tank that minimized the difficulty of filming through water, she fed a reticulated moray a live fish.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The video showed something a little intimidating. After the moray grabbed lunch in its mouth, the pharyngeal jaws started sliding forward, all the way up the throat, until their sharp teeth were even with the eel's eye.

Dissection revealed that muscles connect the moray's upper pharyngeal jaws to the skull just behind the eyes, and also run from the lower pharyngeal jaws to the point of the eel's chin. When the eel contracts those muscles, the throat jaws open and slide forward, almost out of the mouth of the eel. The pharyngeal jaws then close on the part of the prey that is most deeply in the mouth and drag it back towards the stomach. The eels seem to use their secondary jaws about 90 percent of the time.

A moray eel has another method of dealing with large prey. It will loop its body around a victim, similar to the way a python does; but rather than constricting its prey, a moray pulls its head through the loop, holding the victim in a knot while ripping off bite-size chunks of flesh. For the vast majority of prey species, which are too small for that, the morays use the Alien method, ratcheting them down the hatch without letting go. The strategy is like a snake's, but morays evolved to ratchet front to back, rather than left to right.

In looking at my scar, I now suppose that I am lucky a second set of tooth marks isn't inside the first, reducing the utility of my already sad-looking digiti minimi.

- Video: Watch a Moray Eel Feed

- Vote: The World's Ugliest Animals

- Our 10 Favorite Monsters

Adam Summers (asummers [at] uci.edu) is an associate professor of bioengineering and of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Irvine. His daughter is named Eleanor Elektra Lehman (EEL) in part to memorialize that snaky fish that chomped down on him.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus