Exploding Stars May Have Put Humanity on Two Feet

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

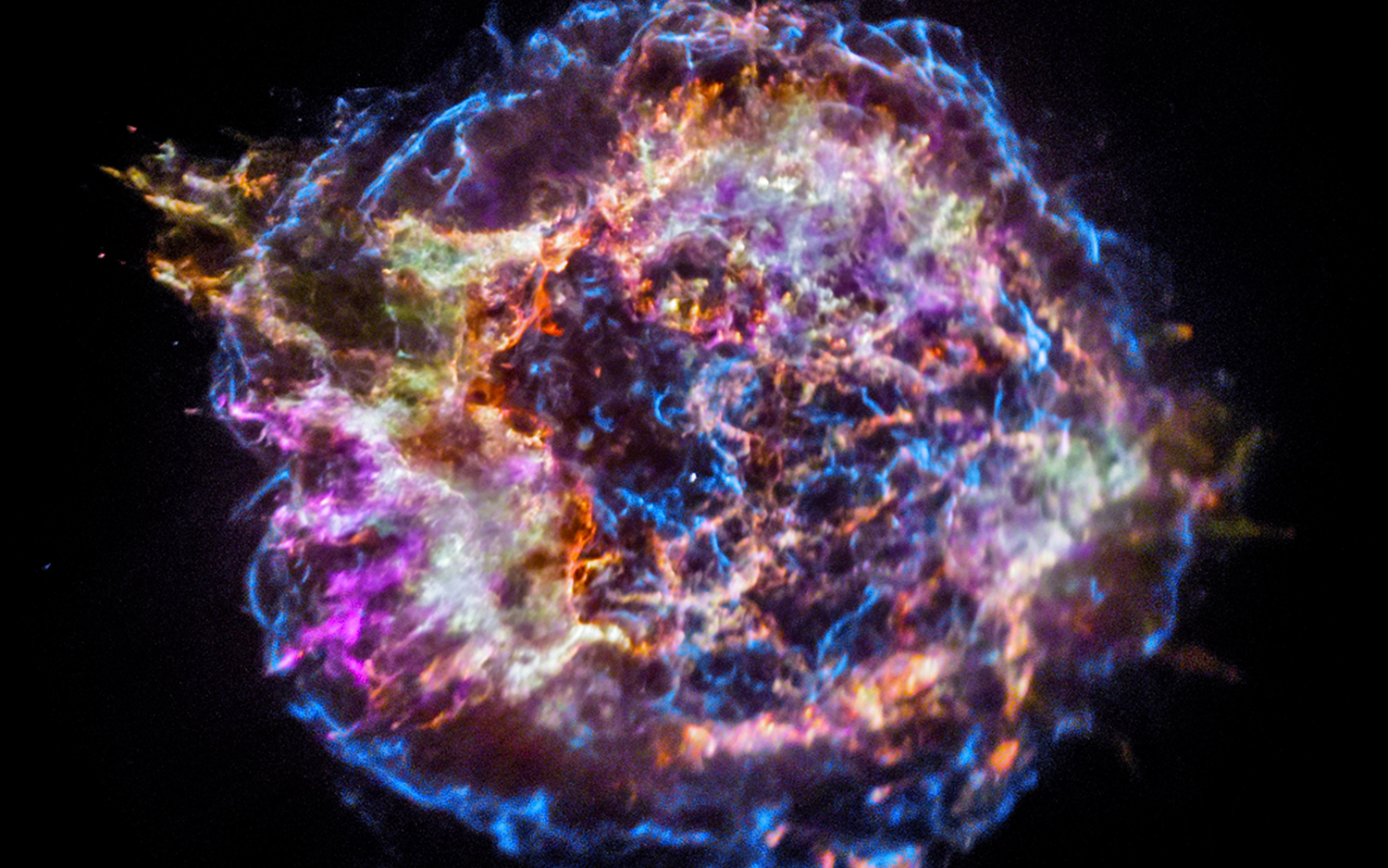

As human ancestors went from swinging through trees to walking on two legs, they may have received a boost from an unlikely source: ancient supernovas.

These powerful stellar explosions may have showered Earth with enough energy to shift the planet's climate, bathing Earth in electrons and sparking powerful, lightning-filled storms, according to a new hypothesis.

Lightning then could have kindled raging wildfires that scorched African landscapes. As savanna replaced the forest habitat, early humans that lived there may have been pushed to walk on two legs, the new study suggests. [Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

However, don't go jumping to conclusions just yet. Many factors likely contributed to the evolution of bipedalism, a process that began many millions of years before these stellar explosions took place, one expert told Live Science.

Clues to the ancient supernovas were found in traces of iron-60 in Earth's crust. This radioactive isotope, or version of iron, originates in stars nearing the ends of their lives; it's thought to have arrived on Earth after the violent explosion of supernovas in our cosmic neighborhood millions of years ago, scientists wrote in the new study.

Prior studies described traces of iron-60 preserved on Earth from stars that blew up, beginning around 8 million years ago. That explosive activity peaked with a supernova (or series of supernovas) that occurred about 123 light-years away from Earth about 2.6 million years ago, the scientists reported. Around that time, the dawn of the Pleistocene epoch, forests in eastern Africa began to give way to open grasslands.

High-energy emissions from the supernovas may have been strong enough to penetrate the troposphere, ionizing Earth's atmosphere and affecting the planet's weather, lead study author Adrian Melott, a professor emeritus with the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Kansas, told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers estimated that energy infusions from supernovas could have increased atmospheric ionization by a factor of 50; this would have greatly increased the likelihood of cloud-to-ground lightning, which in turn could have sparked more wildfires, Melott said.

While the scientists could not calculate precisely how many additional lightning events would result from a 50-fold boost in ionization, "the potential is there for a large increase," they wrote in the study.

Today, most wildfires are caused by human actions; before that, "lightning was the single biggest cause of wildfires," Melott explained. Forests scorched by wildfires would give way to grasslands; more open savanna meant more walking from tree to tree, which would then put evolutionary pressure on human relatives to spend more time on two legs.

Yet hominins were already becoming upright walkers long before the supernova activity peaked, William Harcourt-Smith, an assistant professor of paleoanthropology with Lehman College at The City University of New York, told Live Science in an email.

The first evidence for bipedalism in ancient humans dates to approximately 7 million years ago, and the transition to full bipedalism was well underway by around 4.4 million years ago, said Harcourt-Smith, who was not involved in the study.

"By 3.6 million years ago, we have proficient bipeds, like 'Lucy,' and by 1.6 million years ago, [we have] obligate bipeds very similar to us," he explained.

Bipedalism was energy efficient, freed up hands for carrying, and offered improved visibility of faraway predators or resources. The shift to fully upright walking "most certainly relates to the opening up of grassland habitats and adapting to this kind of environment," Harcourt-Smith said. Yet the study does not provide compelling geologic evidence of wildfires as the main cause for those dramatic changes in Africa's ancient habitats, he said.

What's more, the destructive power and scope of those hypothetical wildfires hinges on a significant increase in lightning as a result of the supernovas, a variable that the researchers were "unable to estimate," they wrote in the study.

The findings were published online today (May 28) in The Journal of Geology.

- Image Gallery: Prehuman Species Sheds Light on Bipedalism

- 15 Amazing Images of Stars

- See Images of Our Closest Human Ancestor

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus