Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ultima Thule is lumpy, and scientists aren't sure why.

Just after midnight on Jan. 1, NASA's New Horizons spacecraft zoomed past Ultima Thule, a small, frigid object that lies about 1 billion miles (1.6 billion kilometers) beyond the orbit of Pluto.

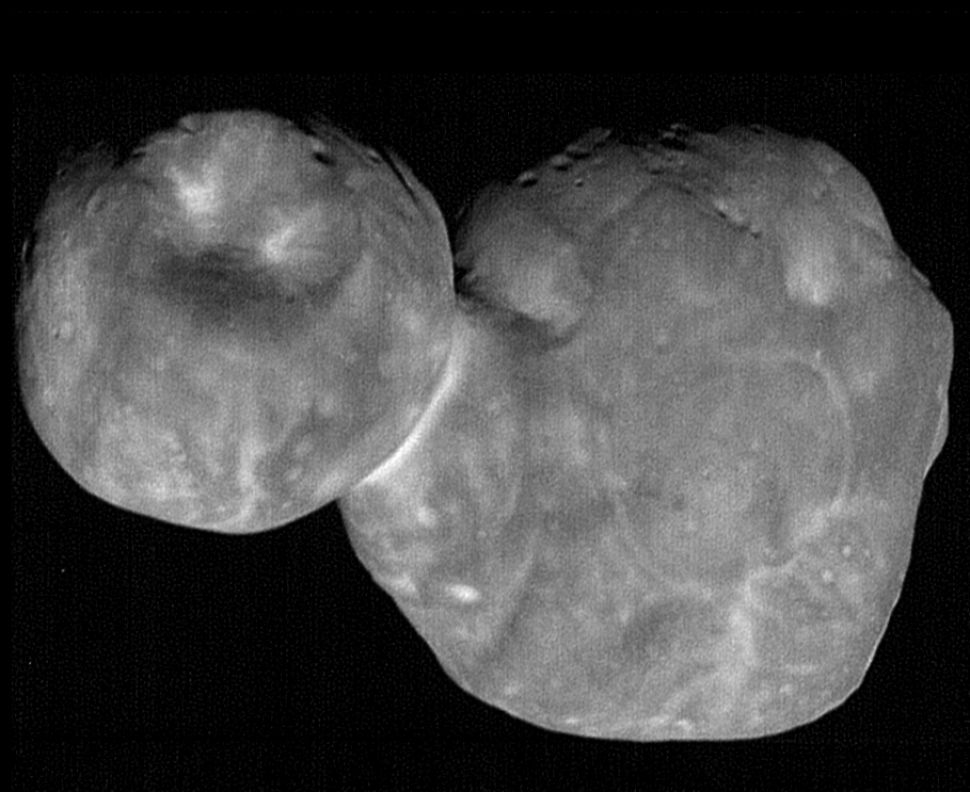

The photos New Horizons captured during that epic encounter revealed a world unlike any other ever seen up close. The 21-mile-wide (33 km) Ultima Thule is bilobed and therefore resembles a reddish snowman — if that snowman had been flattened like a pancake.

Related: New Horizons' Ultima Thule Flyby in Pictures

"These are not spherical lobes at all," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said April 23 during a presentation at the Outer Planets Assessment Group meeting at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C.

"That caught us by surprise," Stern added. "I think it caught everybody by surprise."

New Horizons imagery also revealed a number of abutting mound-like features on the larger of the two lobes, which mission team members call Ultima. (The smaller lobe, naturally, is Thule.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They seem to be raised, but exactly what causes them we're not sure," Stern said. "It's still early days."

An early hypothesis held that the mounds resulted from convection of low-temperature ice, which was driven by the heat generated by the radioactive decay of aluminum-26. But further work suggests that this is an unlikely scenario, Stern said. The team now thinks the mounds may be the retained outlines of the small planetesimals that came together to form the Ultima lobe long ago.

"But there could be other processes as well," Stern said. "So, this is an active topic of debate."

Ultima Thule coalesced from a cloud of rocky, icy material far from the sun. These smaller chunks first formed two larger objects, which then apparently orbited a common center of mass as a binary pair, Stern said. These two bodies then slowly merged to form Ultima Thule (which is officially known as 2014 MU69).

The mission team has been able to put some "speed limits" on that merger, thanks to computer simulations. For example, if the two lobes had come together at about 22 mph (35 km/h), they likely wouldn't have merged at all; the collision would have been a glancing one, and Ultima and Thule would have gone their separate ways, Stern said.

A collision at 11 mph (18 km/h) would lead to a merger, but not one generating an object with two relatively intact lobes like Ultima and Thule; there would be considerable distortion, Stern said. So, the New Horizons team thinks the collision occurred at even slower speeds — perhaps around 5.5 mph (8.9 km/h).

Indeed, the result of simulations with a 5.5-mph merging speed "is strikingly like what we actually observe," Stern said.

Mission scientists have seen no evidence of any type of atmosphere on Ultima Thule, nor have they spotted any signs of satellites or ring systems, he added during Tuesday's talk. But the team isn't done looking on these fronts; it will take another 16 months or so for New Horizons to finish beaming all of its encounter data home to Earth.

The Ultima Thule flyby was the second such encounter for New Horizons, which famously cruised past Pluto in July 2015, providing the first good looks at that complex and surprisingly active world. And we may get further close-ups from New Horizons in the future. The spacecraft is in good health and has enough fuel to zoom past a third object, if NASA approves another mission extension, Stern has said.

- New Horizons' Historic Flyby of Ultima Thule: Full Coverage

- Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures

- New Horizons May Make Yet Another Flyby After Ultima Thule

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter@michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus