Mysterious Mummy Taken from Peru a Century Ago Was the Body of a Teen Boy

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

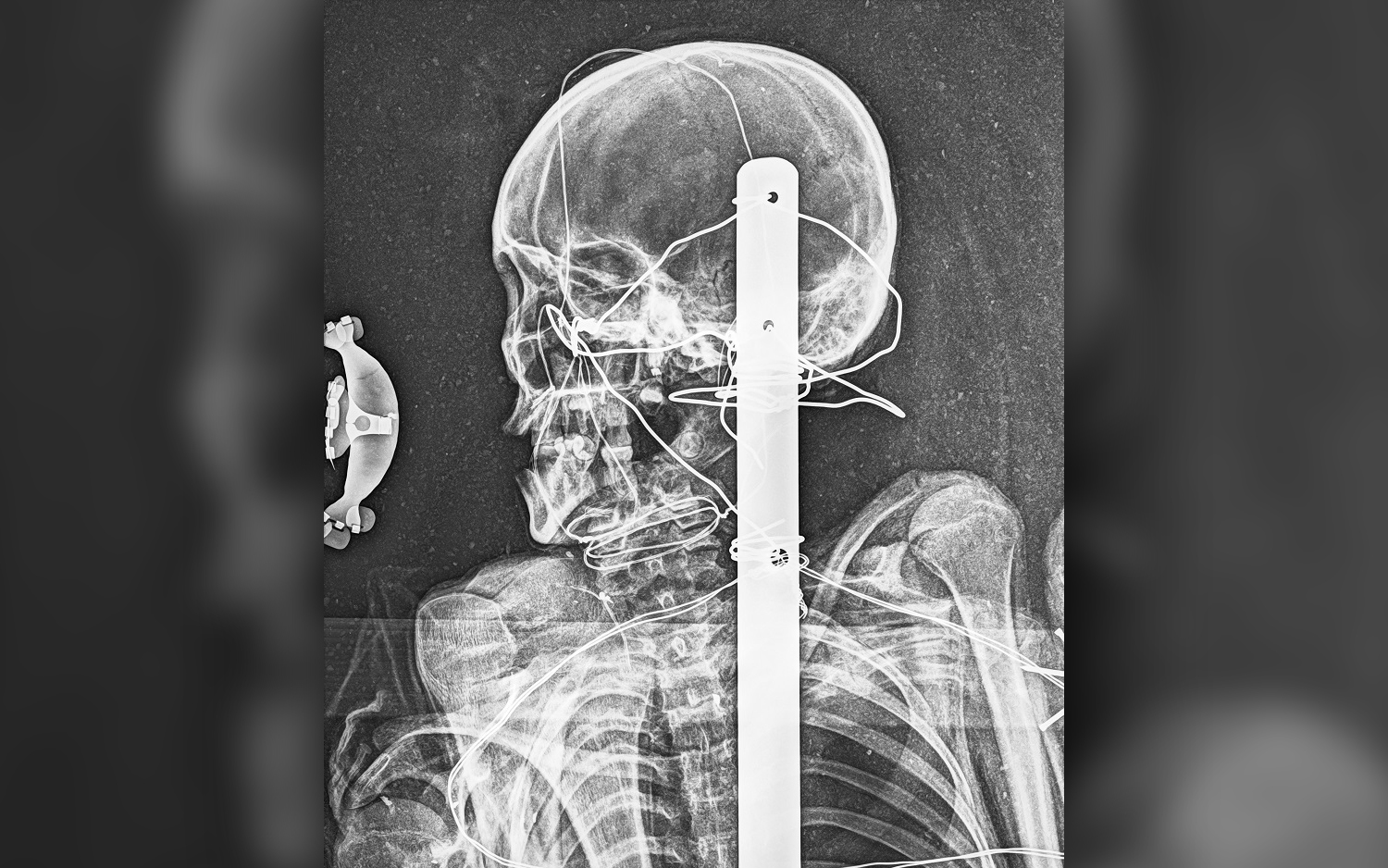

The first X-rays of an ancient Peruvian mummy — taken from the country about 100 years ago by an American railroad worker — recently uncovered long-hidden clues about its mysterious origins.

The mummy has been part of the collection at the Everhart Museum of Natural History, Science and Art in Scranton, Pennsylvania, for nearly a century. But very little was known about the mummy when the museum acquired it in the 1920s. Over the decades that followed, the mummy's fragile condition discouraged invasive examinations that could have revealed clues about its origins.

However, museum officials finally know a little more about this intriguing mummy. After X-raying it for the first time, they discovered that the mummified person was younger than they thought — a teen, rather than an adult male. And clues in its skeleton hinted that the boy may have suffered from health problems before his death, experts told Live Science. [Photos: Hundreds of Mummies Found in Peru]

The mummy's journey from Peru to Pennsylvania was both long and strange. In 1923, a Scranton dentist named Dr. G. E. Hill donated the mummy to the museum; Hill had received the mummy from his father, who brought it from Peru when he returned home after working on the railroads, Everhart Museum curator Francesca Saldan told Live Science.

"Other than that, we really have no documentation about how he acquired it or where in Peru it actually came from," Saldan said.

According to the museum's archives, curators at the time identified the mummy as belonging to the Paracas culture — one of the oldest in South America — which flourished from 800 B.C. to 100 B.C. When the museum acquired the mummy, it was in a fetal position; traditional Paracas burial practices usually swaddle mummies in fabric, but this mummy wasn't wrapped up. However, a textile imprint was pressed into one of the mummy's knees, suggesting that at one point it had a fabric cover that was then lost, Saldan said.

Secrets of the bones

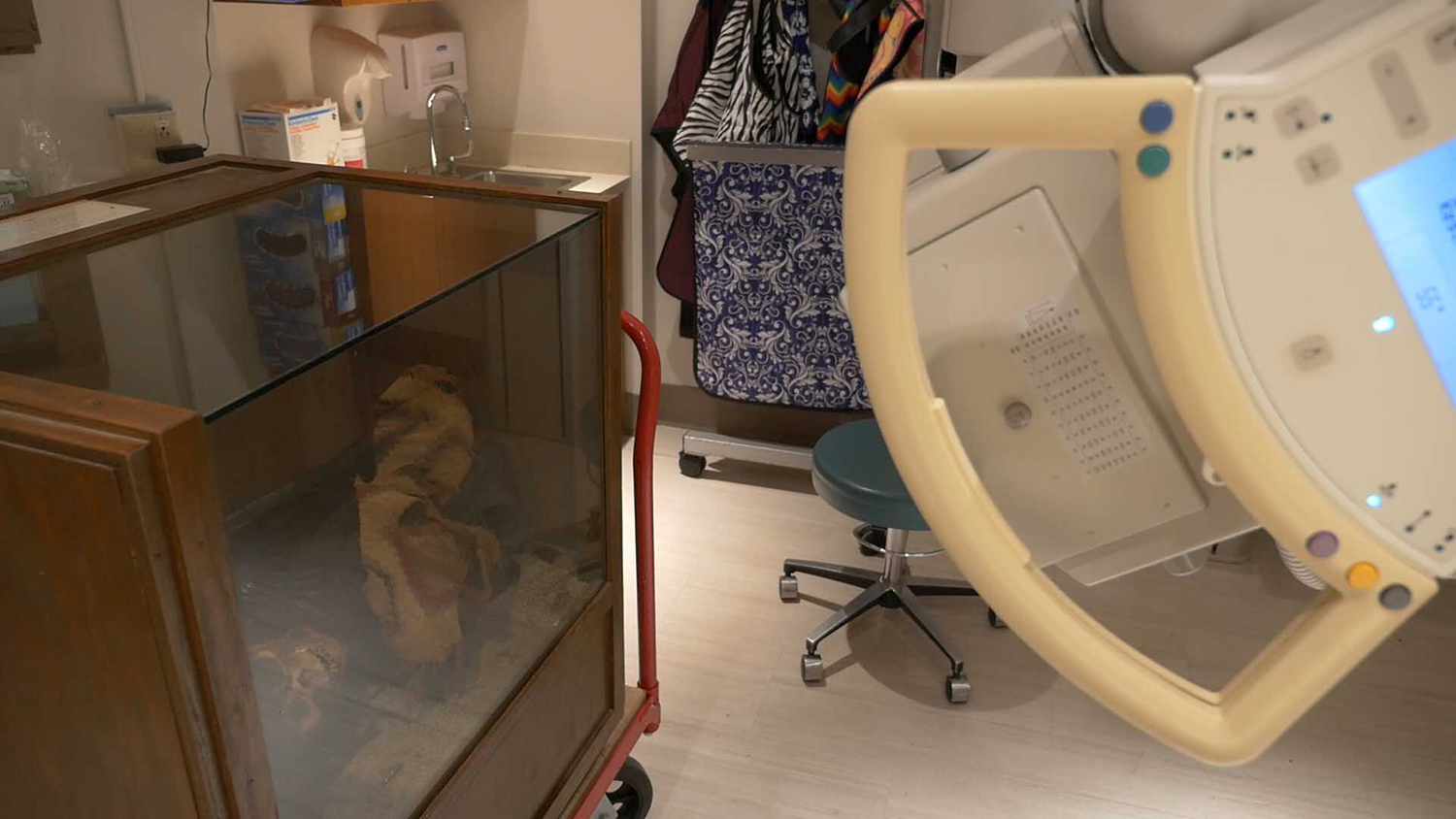

Computed X-ray tomography (CT) scans are typically used to examine preserved soft tissues. But the mummy had been kept in a large display case made of wood and glass since the 1950s. The unwieldy case was too big for a CT scanner, so the museum turned to Geisinger Radiology in Danville, Pennsylvania, to conventionally X-ray the mummy and learn what they could from its bones, Dr. Scott Sauerwine, medical director at Geisinger, told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

X-raying the mummy wasn't easy; its position inside the large case prevented the technicians from getting a clear view of the pelvis. But they were able to find good angles of the skull and other parts of the body.

"In some of the bones, the growth plates weren't fused, and we estimated the age to be in the late teens," Sauerwine said.

When the radiologists X-rayed the mummy's feet, they noted that several toes were missing. Amputations have been around for thousands of years, and it's possible that the teenager lost his toes to frostbite or infection, Sauerwine suggested. Then again, the toes may also have broken off after mummification due to rough handling, he added.

Other than the missing toes, there were no signs of trauma or healed fractures in the body, and there was no clear indication from the bones of what might have caused the teen's death. However, the radiologists did detect abnormal calcium deposits in the spine.

"We see spine abnormalities like this with aging — but this person was not old," Sauerwine said. In this particular case, the teenager likely suffered from a metabolic disorder such as pseudogout (a type of arthritis) or hypoparathyroidism (reduced production of parathyroid hormone).

Could those conditions have been severe enough to cause the teen's death? It's an interesting angle to consider, but it's impossible to say for sure, Sauerwine said.

The mummy is now on display at the Everhart Museum for the first time since the 1990s, as part of the exhibit "Preserved: Traditions of the Andes," open from March 9 to April 7.

- Photos: The Amazing Mummies of Peru and Egypt

- Photos: Mummy Hair Reveals Ancient Last Meals

- Image Gallery: The Faces of Egyptian Mummies Revealed

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus