Unvaccinated Oregon Boy Is Diagnosed with Tetanus, the State's 1st Child Case in 30 Years

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

While playing outside on a farm in Oregon, a 6-year-old boy fell down and cut his forehead.

His parents cleaned and sutured his wound at home, and for a few days, everything seemed all right, according to a new report of his case. But six days after his fall, the boy began crying, clenching his jaw and having muscle spasms. His symptoms got worse, and when he started having trouble breathing, his parents called emergency services, who airlifted the boy to a hospital. [9 Weird Ways Kids Can Get Hurt]

There, doctors diagnosed the boy with tetanus — making him the first documented case of the infection in Oregon in more than 30 years, according to the report, published today (March 7) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

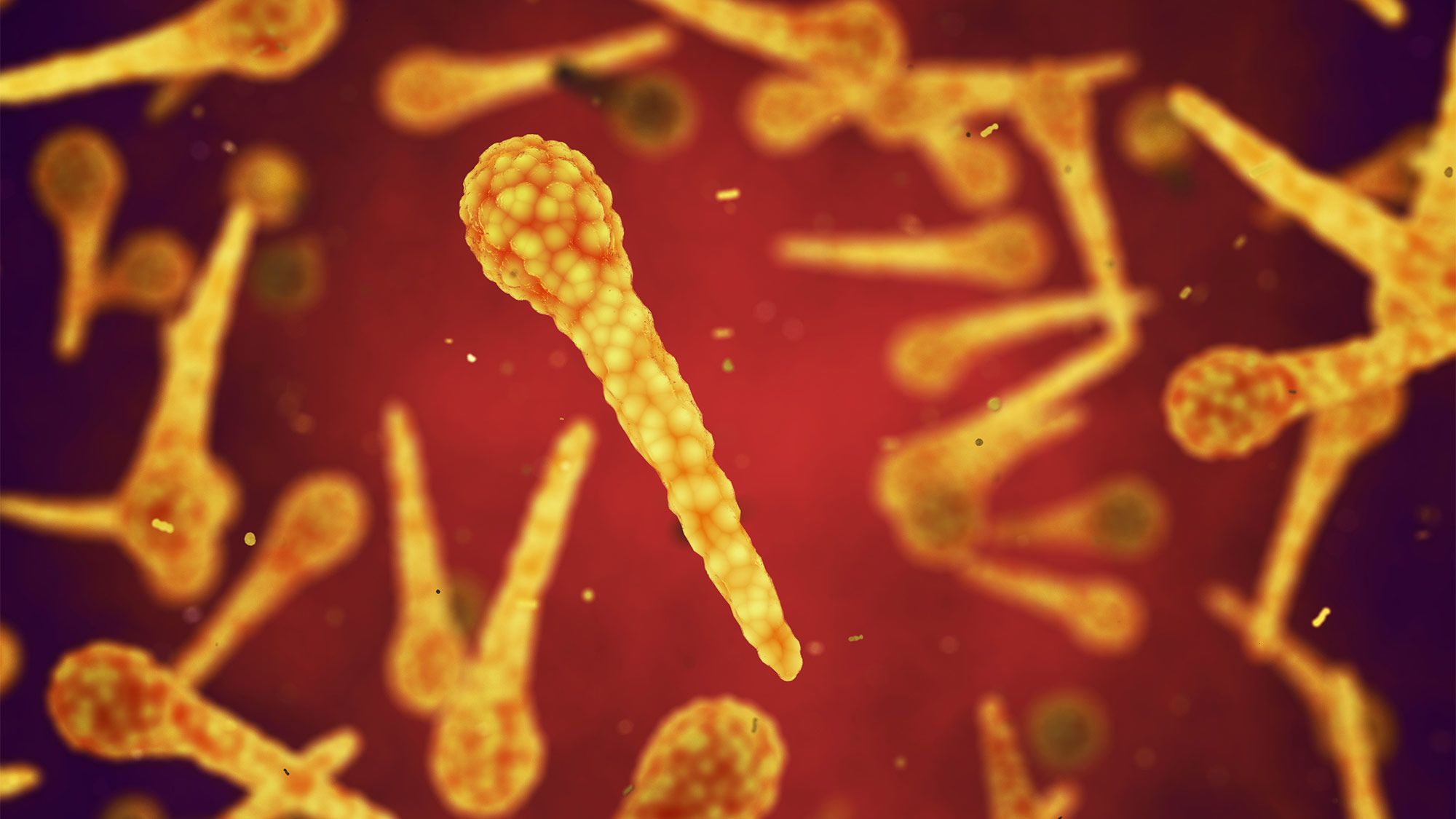

Tetanus is an infection caused by the bacterium Clostridium tetani, but it is preventable thanks to the tetanus vaccine, the CDC says.

The boy in the case, however, had not received his tetanus vaccine, nor any of the other vaccines recommended for a child his age, according to the report.

A serious and expensive illness

When the boy arrived at the hospital, his jaw muscle was spasming, and though he wanted water, he couldn't open his mouth to drink. He was also experiencing a condition called opisthotonus, or an arching neck and back, which got progressively worse.

The boy was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), where he was given the tetanus vaccine as well as medication containing antibodies to fight the bacteria. These antibodies had been taken from people who had been vaccinated against tetanus. The boy needed to be cared for in a darkened room with earplugs, because stimulation made his muscle spasms worse, the report said. He was also placed on a ventilator to help him breathe and given medications for his blood pressure and muscle spasms.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The boy remained in the ICU for 47 days, followed by several weeks of intermediate care and rehab, the report said. Finally, with a medical bill exceeding $800,000, the boy was able to return to his normal life, which included running and bicycling.

"Ubiquitous" bacteria

Despite recommendations by doctors to give the boy the second dose of tetanus vaccine along with other required vaccinations for children, the family declined, according to the report.

Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious-disease specialist at Vanderbilt University who was not involved with the case, said that the boy's infection was "a tragic event that [was] completely preventable."

And the parents' decision to not give him a second dose of the tetanus vaccine amounted to a "second tragedy," Schaffner told Live Science.

But not all is grim: Save for the occasional anti-vaxxer parents, most children do receive their tetanus shots. And thanks to the vaccine, cases of this infection have decreased by 95 percent and deaths by 99 percent since the 1940s.

The bacterium that causes tetanus is "ubiquitous, it's everywhere," Schaffner said. Though often associated with rusty nails, the bacteria don't really have to do with rust — people can be infected by any kind of deep, penetrating wound. Indeed, C. tetani is found everywhere in the environment, including in soil, dust and feces.

The only way to protect yourself is to get vaccinated, Schaffner said. What's more, a previous tetanus infection doesn't confer immunity against future infections. The vaccine works in part by combating toxins created by tetanus bacteria, rather than the bacteria themselves.

The CDC recommends multiple doses of the tetanus vaccine (that also protects against other infections such as whooping cough) for children: one dose at 2, 4 and 6 months each; one at 15 to 18 months; and one at 4 to 6 years old. Pre-teens should also receive another version of that tetanus vaccine and people should receive tetanus booster shots once every 10 years.

Even if you're up to date on your tetanus shots, however, with any kind of intense penetration wound, you should seek medical care to clean and suture it, Schaffner said. And if you haven't had a booster shot in over five years, doctors will recommend you get one, he added.

- 7 Absolutely Horrible Head Infections

- 27 Devastating Infectious Diseases

- 8 Awful Parasite Infections That Will Make Your Skin Crawl

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus