500 Million-Year-Old Worm Superhighway Revealed in Ancient Seafloor

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About a half billion years ago, an ancient sea covered what is now the northernmost stretches of Canada. Its seafloor was long thought to be a dead zone, devoid of the oxygen needed to support life.

But as it turns out, minuscule worms lived quite happily in these ocean sediments — they even created their own "superhighway" of tunnels by burrowing through the soil.

Traces of these fossilized tunnels were found in rocks collected decades ago from Canada's Mackenzie Mountains in the Northwest Territories. But scientists more recently found the tiny tunnels only after reanalyzing them, they reported in a new study.

Their discovery sheds light on the region's ocean ecosystems during the Cambrian era (543 million to 490 million years ago), suggesting that these environments may have harbored more oxygen — and more life — than expected, according to the study. [Cambrian Creatures Gallery: Photos of Primitive Sea Life]

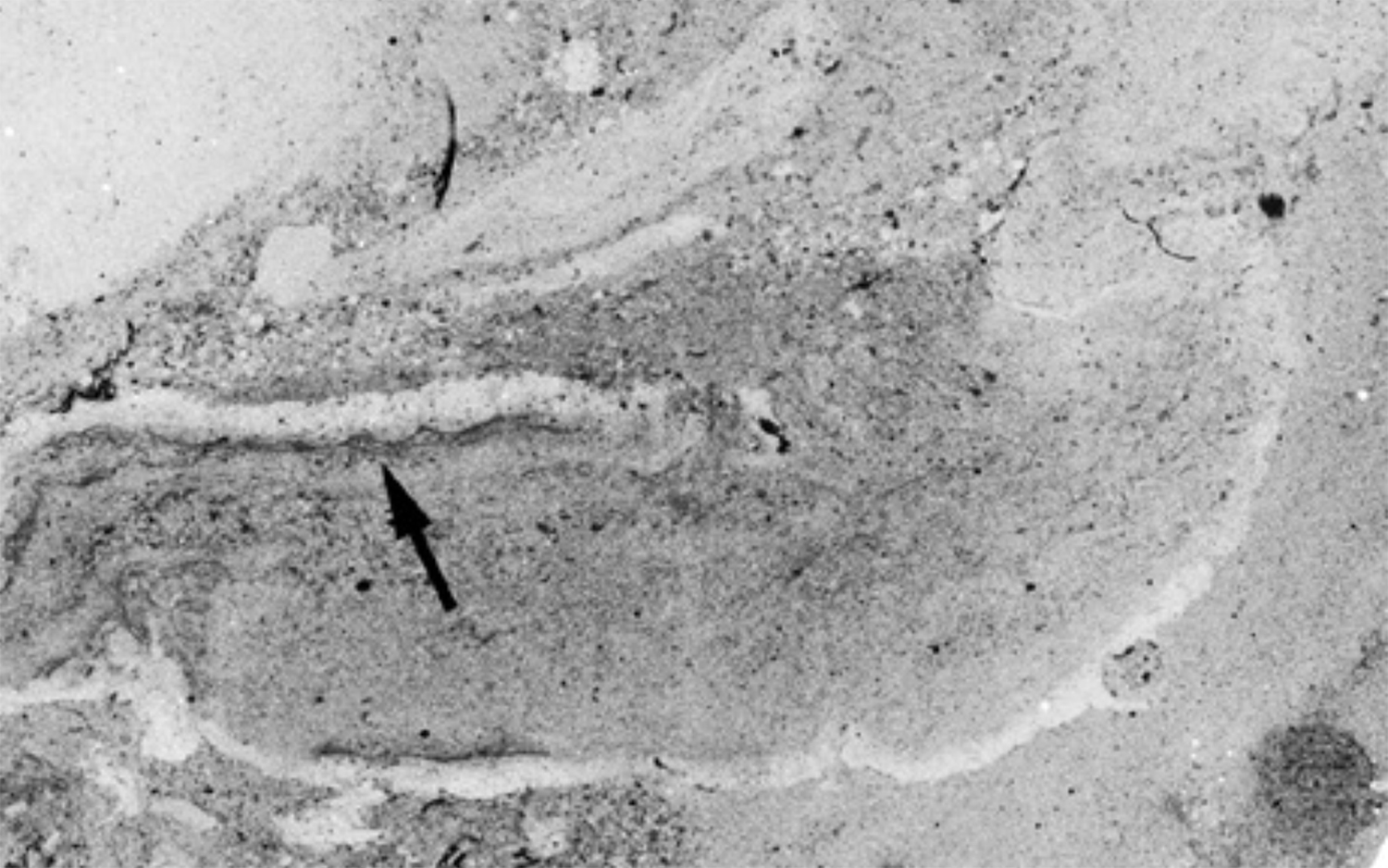

The tunnels that the worms left behind in the weathered rock weren't visible to the naked eye, and were detected purely by chance, lead study author Brian Pratt, a professor of geological sciences with the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, told Live Science in an email.

Pratt and his co-author Julien Kimmig, a collections manager of invertebrate paleontology with the Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum at the University of Kansas, found the tunnels while collaborating on another study published in 2018. (They described a "poop picnic" enjoyed by Cambrian worms at the same site where the worm tunnels were found, Pratt said.)

Pratt and Kimmig were preparing samples for the 2018 study — sawing and grinding the rocks — when they discovered something that they hadn't seen before.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I noticed some slight variation in shading," Pratt said. He dampened the smooth surface of a rock sample with alcohol, scanned it on a flatbed scanner and enhanced the image brightness and contrast. Suddenly, "a riot of burrows appeared," he said. Some areas were crisscrossed by just a few tunnels, but other portions of rock were "completely churned" by the worms' activities, he said.

The preserved tunnel shapes were exceptionally well-defined and had not collapsed, hinting that the sediment around them was firm and not "soupy," the study authors wrote.

In width, the tunnels measured from 0.02 to 0.6 inches (0.5 to 15 millimeters), made by worms ranging from about a millimeter in length to finger-size, according to the study. Most of the burrows were tiny, dug out by worms that scoured the ocean sediment looking for organic matter to eat. The rare, larger tunnels likely housed predatory filter-feeders — "animals that projected a feeding apparatus up into the water column to catch organic particles and tiny animals," Pratt said.

Also contained in the rock were the preserved bodies of worms — not the worms that dug the tunnels — and "large poops" containing shreds of body tissues that likely belonged to other worms that were eaten, according to Pratt.

Together, this evidence presents a fascinating snapshot of an ancient seafloor habitat, in an ocean ecosystem that was far richer — in oxygen and species — than expected, the scientists reported.

The findings were published online in the March issue of the journal Geology.

- These Bizarre Sea Monsters Once Ruled the Ocean

- Photos: 'Naked' Ancient Worm Hunted with Spiny Arms

- Photos: 508-Million-Year-Old Bristly Worm Looked Like a Kitchen Brush

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus