Those Tiny Cotton Sprouts China Grew on the Moon? They’re Dead Now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

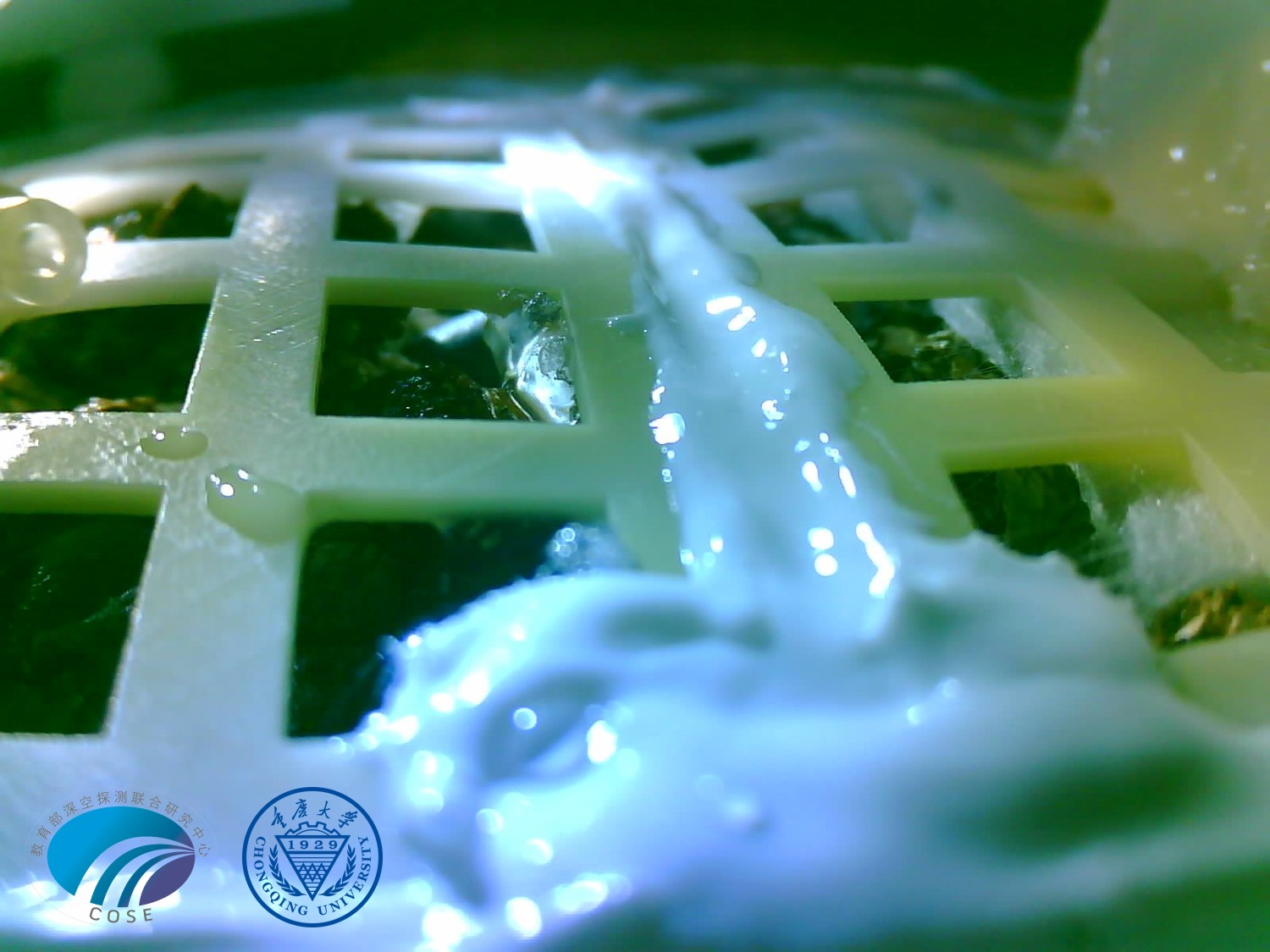

They were the little cotton sprouts that could: a handful of seedlings that poked themselves up from the dirt inside a small biosphere on China's lunar lander, Chang'e-4.

Yes, the plants were stunted compared with the earthbound control plants. But they had just survived a space launch and difficult journey to the moon, and were growing in the low gravity and high radiation of extraterrestrial space. They were the first plants ever to grow on the lunar surface. None of the other species that made the trip with them showed any similar signs of life.

Now they're dead. And it's all the moon's fault.

During a news conference today (Jan. 16), project leader Liu Hanlong explained the plants' deaths in their little, faraway can, the Hong Kong publication GB Times reported.

As night fell on the region of the far side of the moon where Chang'e-4 sits, temperatures plunged in the 5.7-lbs. (2.6 kilograms) mini biosphere. Hanlong reportedly said that the temperature inside the chamber had fallen to minus 62 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 52 degrees Celsius), and could continue to plunge to minus 292 degrees F (minus 180 degrees C). The experiment is effectively over, as the lander has no onboard mechanism for keeping the experiment warm without sunlight.

So what, precisely, would have happened to the extraterrestrial growth as temperatures plunged?

Some plants are better at dealing with cold than others, as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) explained in a post. As days shorten and temperatures drop, the plants flood their cells with sugar and other chemicals to lower the freezing point of the water inside. This process is important because it keeps intracellular water from turning to ice crystals that expand and shred cells from the inside. Other plants also toughen cell membranes, or — in extreme environments, plants survive freezes by dehydrating themselves, literally pumping water out of the cells.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, according to the FAO, all of these "hardening" techniques require that, for several days, the environment send t signals that winter is coming. This is why sudden frosts can kill even cold-weather plants on Earth. And cotton, native to warm regions on Earth, is not particularly well adapted to the cold in the first place.

The lunar nighttime chill would have been nothing like the gradual seasonal shift to which plants are adapted. During the two-week daylight period, temperatures on the lunar surface can be as high as 212 degrees F (100 degrees C). But when night falls, they can rapidly plunge to minus 279 degrees F (minus 173 degrees C).

So the cold shock to the cotton was likely brutal and sudden. Water in newly formed cells would have turned quickly to ice, flaying them open from the inside. Any buds and leaves would have gone first, according to research published in 2001 in the journal Annals of Botany. A close look at them under microscopes would reveal cell membranes wrinkled and folded on themselves like burst water balloons. The hardier stems would have frozen shortly afterward.

At the same time as the cells froze, that study found, water between the cells would have frozen as well. That process would have sucked more water out of the cells before it could freeze, killing the cotton by dehydration as much as physical destruction.

Though no earthly plant is known to survive at temperatures colder than even the middle of Antarctica, the cotton likely wouldn't have put up a fight to prevent its death without any autumnal light shifts to signal the temperature change.

The end of those cotton sprouts was probably nasty, then. But at least it was quick. We salute the botanical explorers, now frozen in their lunar graves.

- When Space Attacks: The 6 Craziest Impacts

- The Large Numbers That Define the Universe

- Twisted Physics: 7 Mind-Blowing Findings

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus