Petrified Chains of 'Poop' Turn Out to Be One of Earth's Oldest Skeletons

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Mysterious fossils found all over the world belong to creatures that built their own skeletons more than 550 million years ago.

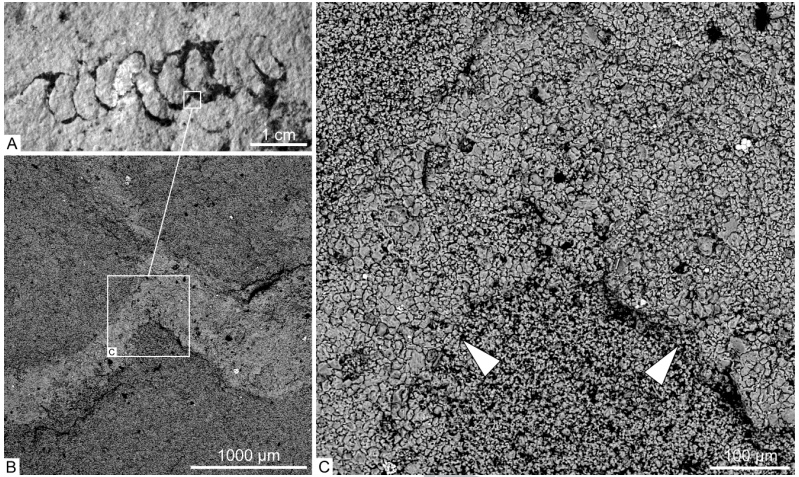

Palaeopascichnus linearis is among the world's oldest skeletal creatures, according to new research published in the October issue of the journal Precambrian Research. These tiny globular, ocean bottom-dwellers may have been amoeba-like creatures that accrued bits of sand and sediment around themselves to create their own exoskeleton. All earlier organisms with similar exoskeletons were much, much smaller, said study leader Anton Kolesnikov, a paleontologist at the Institute of Petroleum Geology and Geophysics at the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the University of Lille in France. [In Images: The Oldest Fossils on Earth]

"It is the oldest known macroscopic skeletal organism," Kolesnikov said of P. linearis.

Mystery fossils

Palaeopascichnus fossils are found the world over in rocks from the Ediacaran period, which spanned from 635 million to 541 million years ago. No one had been able to agree on exactly what the fossils were, though, Kolesnikov wrote in an email to Live Science. Some thought they were trace fossils left behind by some organism shuffling along the seafloor. Others suspected they were coprolites — fossilized poop. Still others argued they were organisms in and of themselves.

Figuring out the answer was difficult because many areas where Ediacaran fossils are found around the world are protected, Kolesnikov said. But in the Olenek Uplift of northeastern Siberia, past the Arctic Circle, Kolesnikov and his colleagues discovered sites where they collected more than 300 new specimens of the fossils. They also discovered more fossils from the area in collections dating back to the 1980s.

"Huge amounts of fossils from Siberia allowed us to experiment with thin sampling, sectioning, cutting, studying in [electron] microscopes" and more, Kolesnikov said.

DIY skeletons

This analysis revealed that the fossils were made up of chains of between two and 40 spherical or oval modules, each between 0.04 inches and 0.2 inches (1 and 5 millimeters) in diameter. Each module was bordered by a fine rim of sediment.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

More than anything, the researchers reported, the fossils looked like today's xenophyophores, which are giant foraminifera. These bizarre creatures are amoebas that protect themselves with "agglutinated tests," or exoskeletons of sediment they cement to themselves with their own excretions. Scientists reporting in a March 2018 paper in the Zoological Journal detailed the discovery of a new species of these xenophyophores, Aschemonella monile, which look remarkably similar to the fossil versions from Siberia.

The oldest microorganisms with agglutinized skeletons date back to about 742 million years ago, the researchers wrote in their new study. But P. linearis, which dates back to around 613 million to 544 million years ago, may be the oldest non-microscopic organism to boast a skeleton. Previously, Kolesnikov said, macroscopic organisms (those visible to the naked eye) weren't thought to evolve skeletons until the Paleozoic. The new findings suggest this happened slightly before that, in the late Proterozoic.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus