500-Year-Old Scroll Reveals King Henry VII's Extraordinary Support of Travelers to New World

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In 1500, just a year after England sent its first British-led expedition to "Terra Nova," the so-called New World, King Henry VII gave a hefty reward to one of the explorers, new research shows.

The king gave an extravagant paycheck of 30 British pounds sterling to William Weston, a Bristol merchant who traveled on the 1499 voyage. Back then, that sum of money was the equivalent of about six years' salary for a laborer, indicating that King Henry VII was pleased with Weston's accomplishments, the researchers said.

They made the discovery by using ultraviolet light to reveal text on a huge parchment that dates back more than 500 years, said study co-researcher Evan Jones, a senior lecturer in economic and social history at the University of Bristol. [Photos: Christopher Columbus Likely Saw This 1491 Map]

In 2009, Jones published a long-lost letter from King Henry VII, in which he stated that Weston was preparing for an expedition to the "new found land," Jones said. This was hardly the first trip to the New World from England. The Venetian explorer John Cabot sailed from the English port of Bristol in 1497 and again in 1498. Finally, in 1499, Weston directed a British-led expedition, with the king's support, the letter showed.

During the recent analysis, Jones worked with Margaret Condon, an honorary research associate at the University of Bristol who is part of the Cabot Project — an international project to research voyages from Bristol during the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Condon painstakingly trawled official tax records to learn more about the adventurers traveling from Europe to North America.

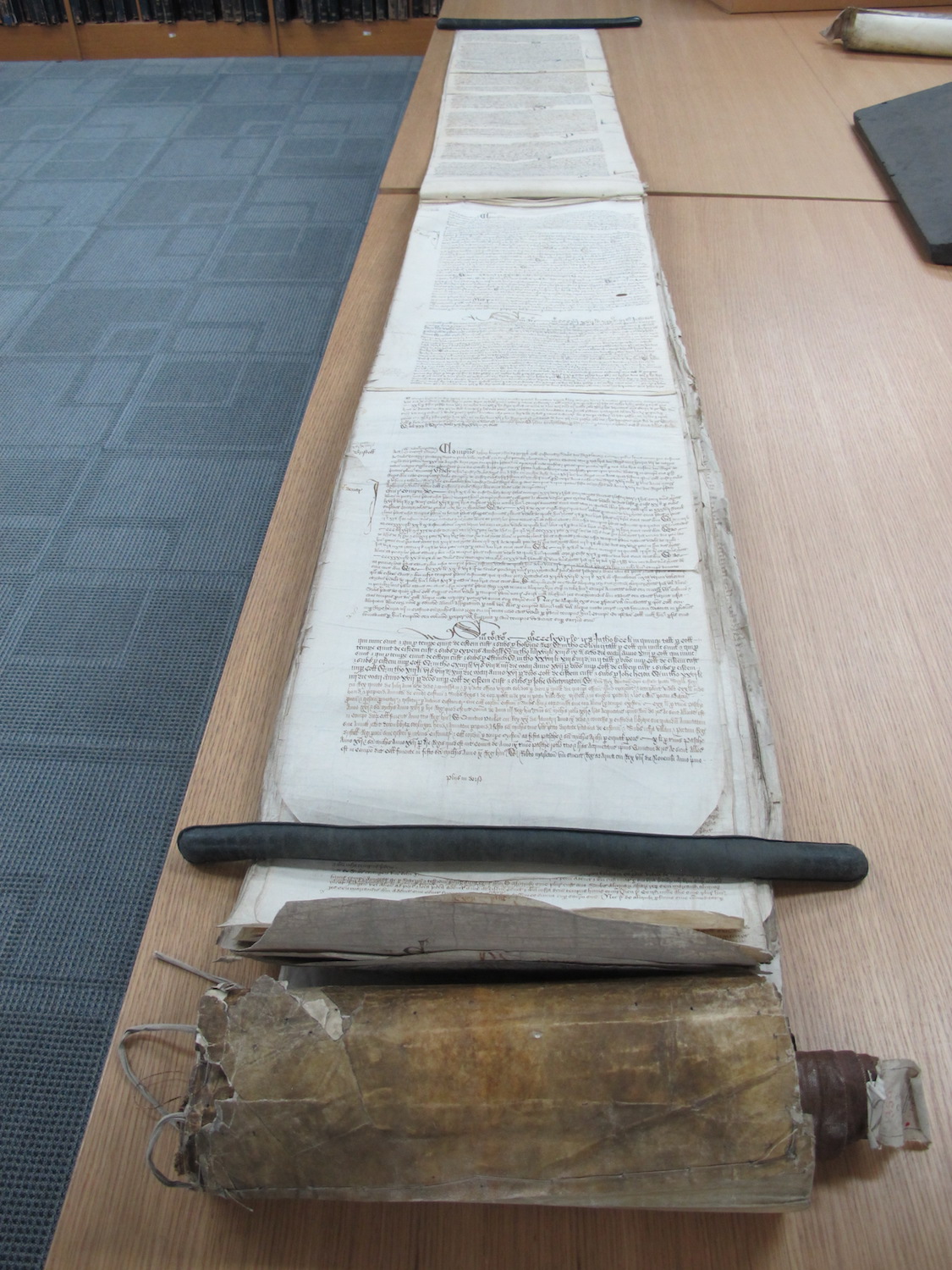

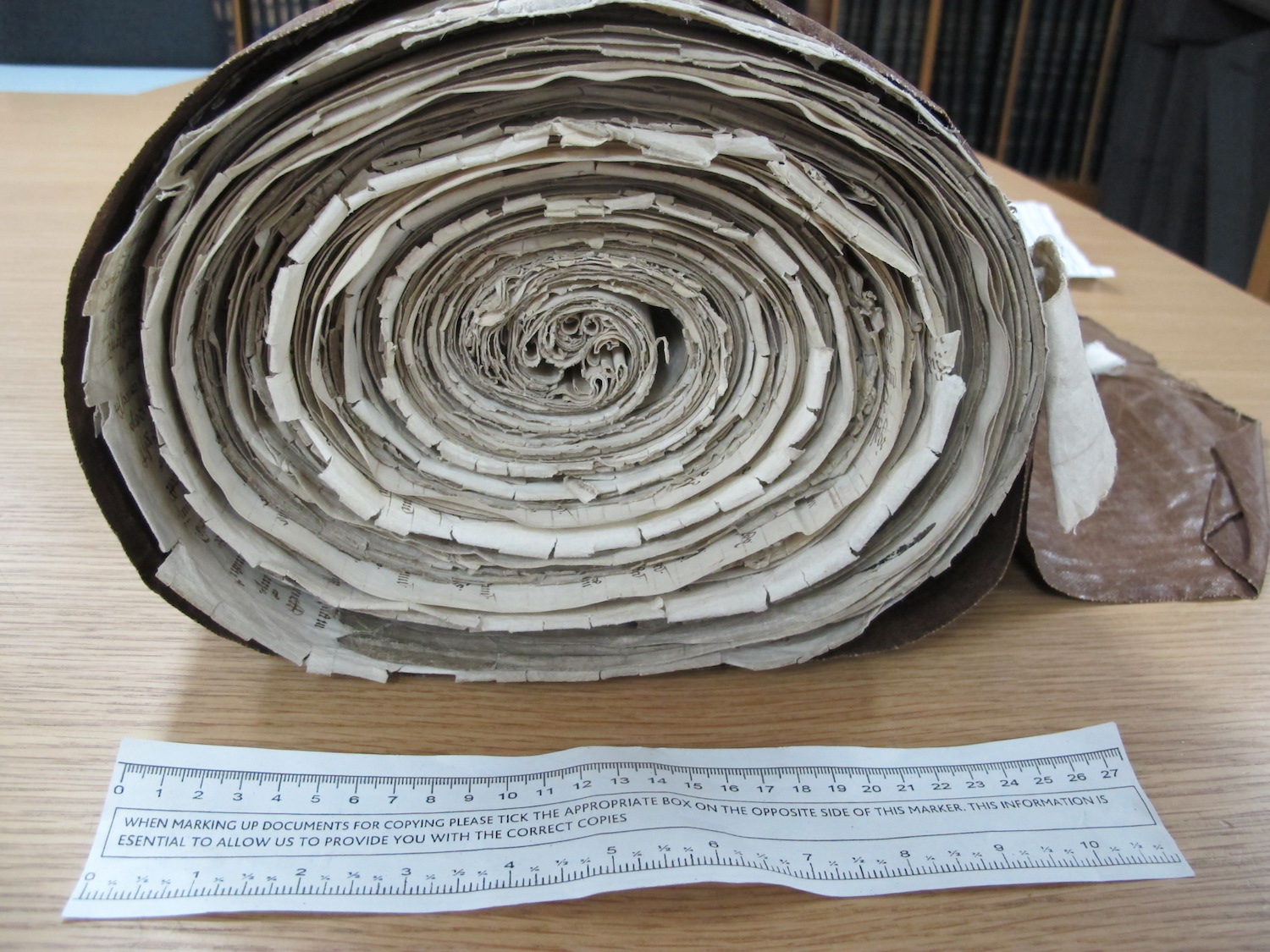

These tax records weren't easy reads. They were written on huge parchment rolls, created from the skin of more than 200 sheep. Each segment on the roll was 6.5 feet (2 meters) long and had ink so faint that it was visible only under ultraviolet light.

"First time I read the roll, I almost missed it," Condon said in a statement. "These rolls are beasts to deal with, but also precious and irreplaceable documents. Handling them, it sometimes feels like you're wrestling, very gently, with an obstreperous [boisterous] baby elephant!"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers also found that Cabot and Weston got rewards in January 1498, after they met with Henry VII. This finding shows that the two explorers were working together before Weston left on the 1499 journey.

In addition, it appears that Weston was likely one of the unnamed "great seamen" from Bristol whom Italian diplomats wrote about during the winter of 1497 to 1498. These letters, sent from London to Italy, describe how Cabot was traveling with Bristol explorers on his 1497 and 1498 expeditions.

It's anyone's guess how Cabot's final expedition in 1498 turned out, as it's unclear whether any of his ships returned to Europe. Perhaps this is why King Henry decided to send another expedition the following year, led by one of Cabot's deputies, the researchers said.

"Finding this new evidence is wonderful," Jones said in the statement. "What’s amazing about these early Bristol voyages is how little we’ve ever known about them."

Jones added that "Cabot’s voyages have been famous since Elizabethan times and were used to justify England’s later colonization of North America. But we've never known the identity of his English supporters. Until recently, we didn't even know that there was an expedition in 1499." [Top 5 Misconceptions About Columbus]

Other evidence from the Cabot Project revealed that Weston was "a bit of a gambler," Condon said. "But then so was Cabot," she said. "Perhaps you had to be, to risk your life on such a dangerous voyage into unknown seas."

Unmapped history

The new findings support two extraordinary claims made by Alwyn Ruddock, a historian at the University of London who died in 2005. Ruddock spent years researching England's first voyages to North America, but she ordered that all her unpublished work be destroyed at the time of her death. Her orders were followed, but her will specified that a book could go forward if it were in press. Ruddock never submitted that book, but she did submit a synopsis for one, and this was shared with Jones. Intriguingly, in one of her findings, she stated that Cabot had explored much of North America's east coast by 1500.

In another one of her claims, Ruddock said that a group of Italian friars who sailed with Cabot on his 1498 expedition went on to found Europe's first Christian colony and church in North America. She also implied that Weston visited this settlement in Newfoundland in 1499, just before he traveled up the coast of Labrador to search for the Northwest Passage around the continent. It was for this that Weston received the reward from the king, the researchers said.

However, historians working with the Cabot Project have a long way to go before supporting or rejecting Ruddock's other claims.

"I think we've got well over half of the documents Ruddock located, but there are definitely more, especially in Italy," Condon said. "She did a lot of work there, including in the private archives of some of Italy's great noble families."

The new study was published online Oct. 2 in the journal Historical Research.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus