Photos: Christopher Columbus Likely Saw This 1491 Map

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

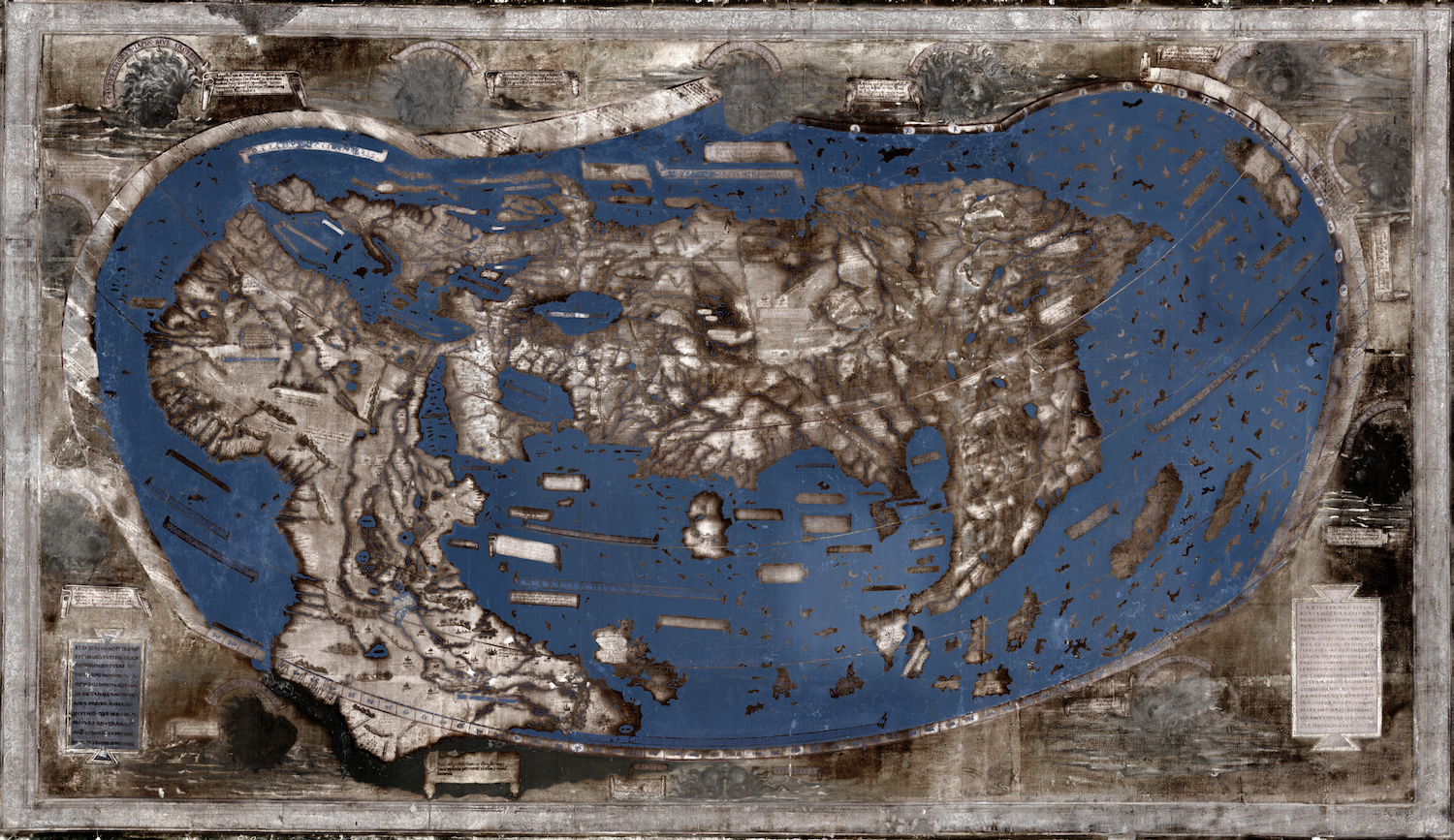

1491 map

The German cartographer Henricus Martellus likely created this map in 1491. But the map has faded over the years, making it challenging to read.

[Read more about the 1491 map]

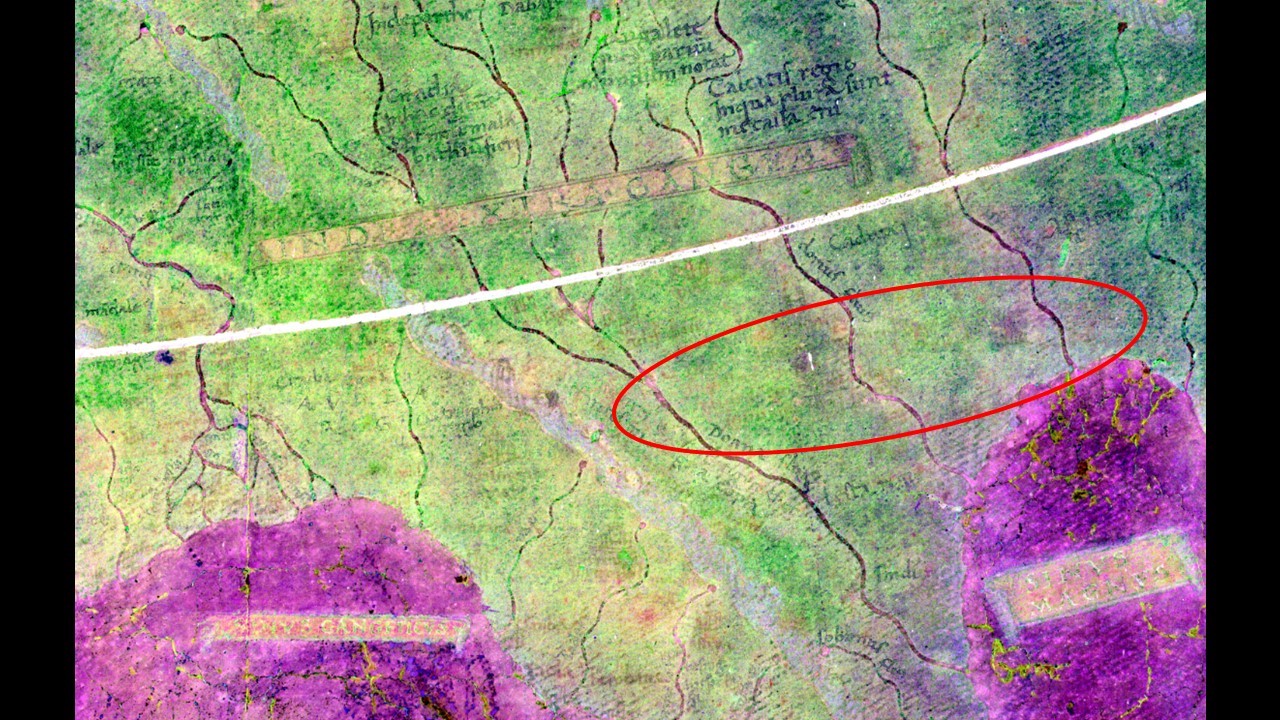

Multispectral image

The researchers used multispectral imaging to reveal the images and text on the map.

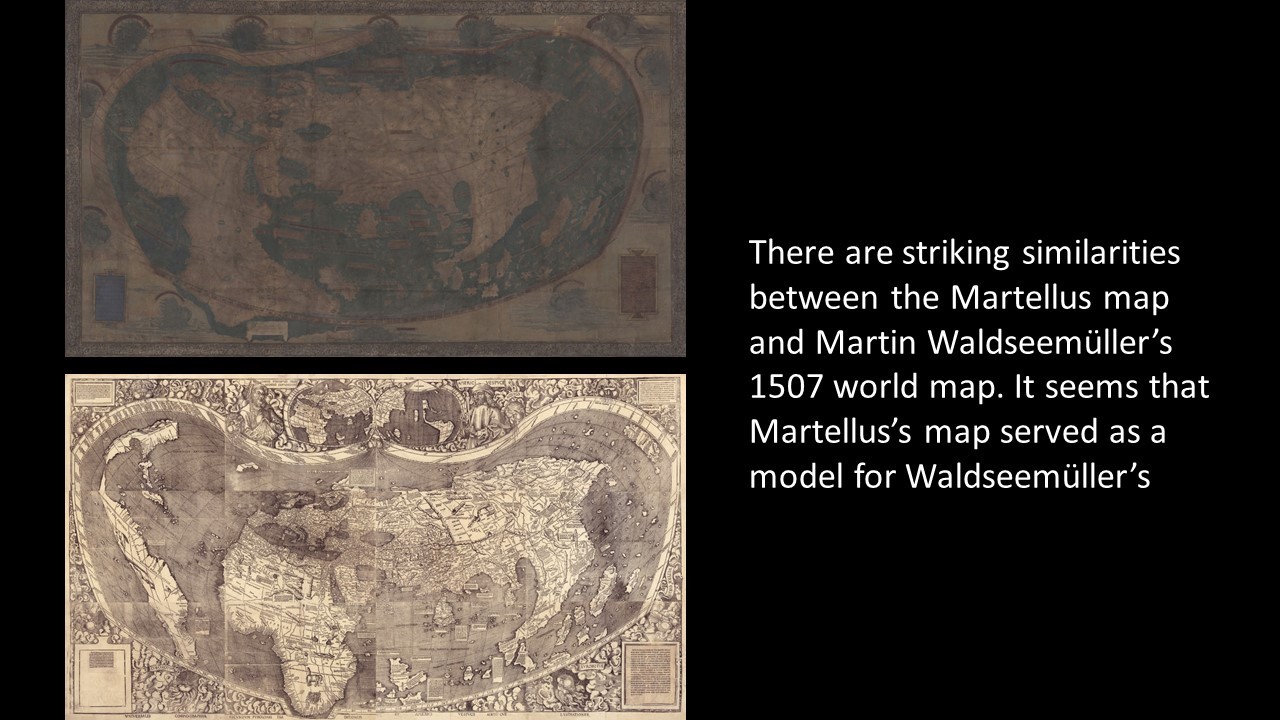

Waldseemüller map

The multispectral imaging allowed the researchers to determine that Martellus' map greatly influenced Martin Waldseemüller's 1507 world map. This 1507 map is famous because it is the first known map to call the New World by the name "America."

Very similar

Notice how similar the 1507 Waldseemüller map (bottom) is compared to the Martellus map (top).

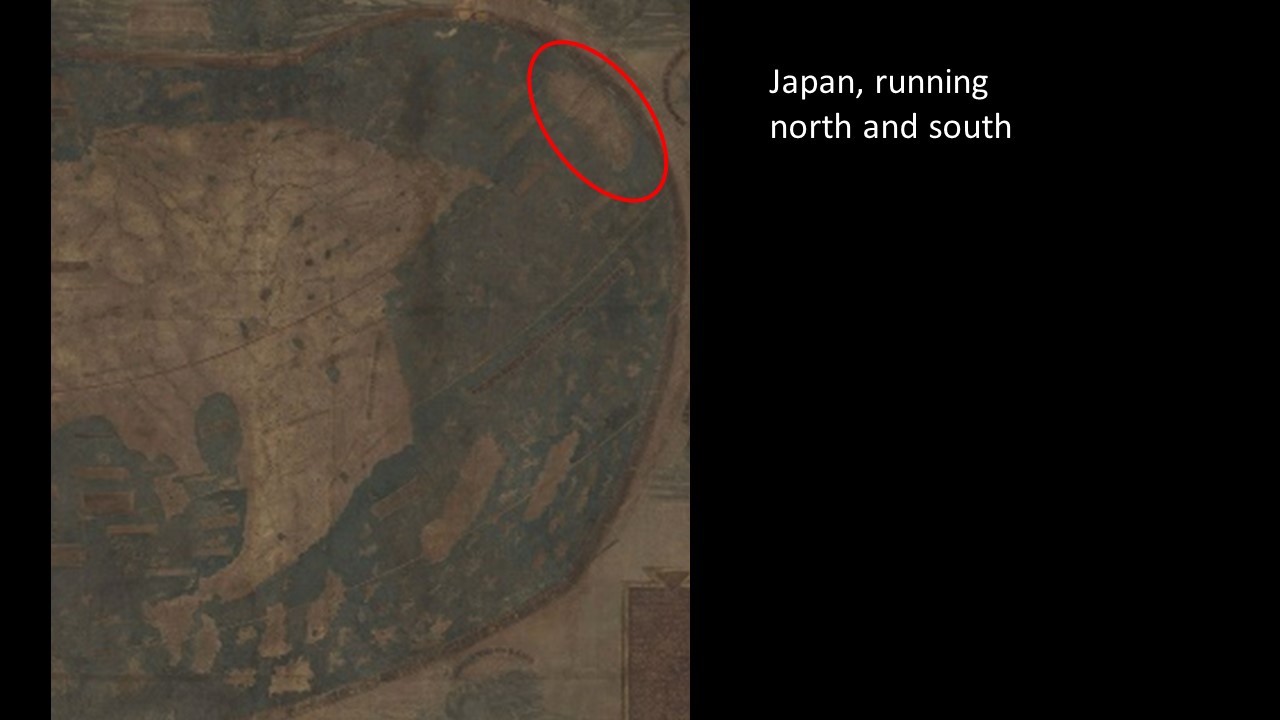

Japan

It's highly likely that Christopher Columbus saw Martellus' 1491 map before his famous 1492 voyage. Researchers figured this out because Martellus drew an elongated Japan running north to south, the only map at this time to do so. And Columbus' son wrote that Columbus thought this detail was true.

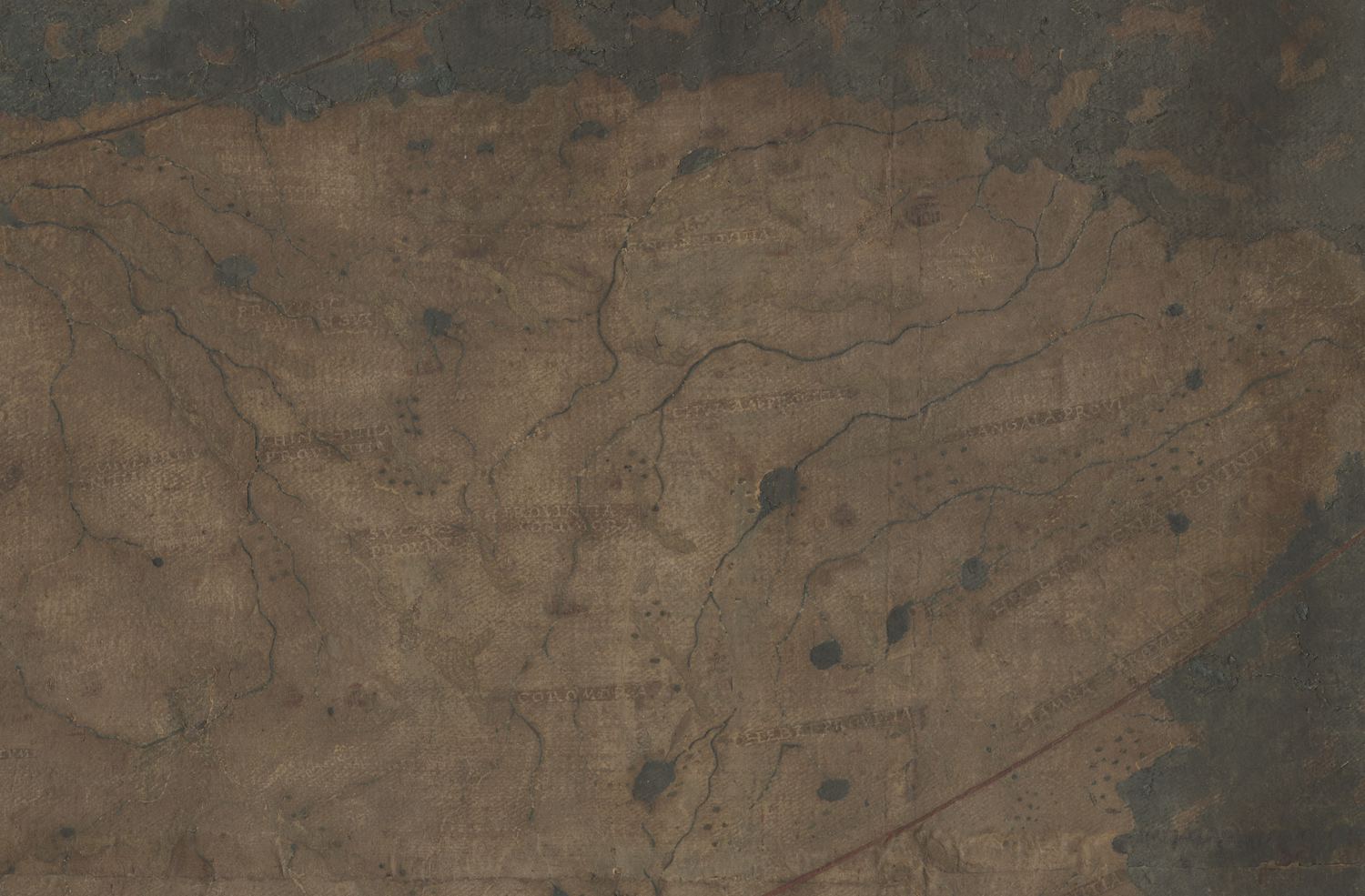

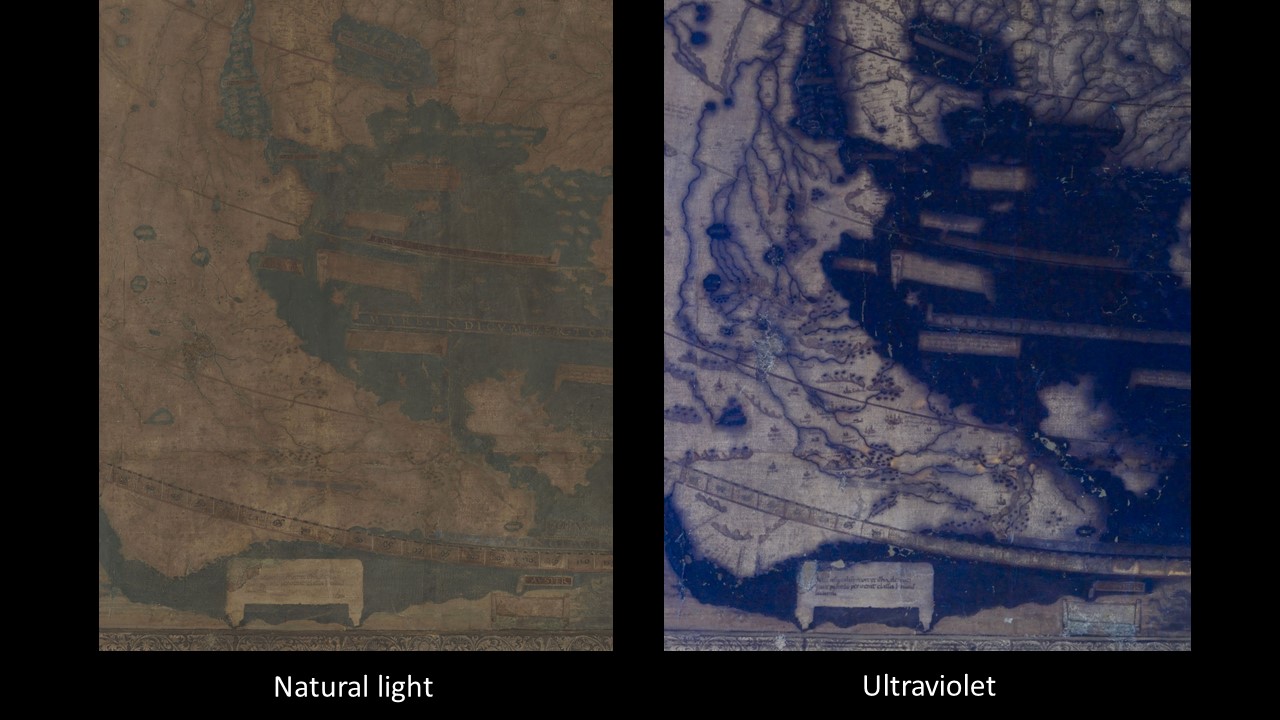

Hard to read

The Martellus map has faded over time. This is what a portion of northeastern Asia looks like in natural light to the naked eye.

Ultraviolet image

This is an ultraviolet image of the same portion of northeastern Asia that Yale University researchers took in the 1960s.

[Read more about the 1491 map]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

More ultraviolet

Here is another natural light and ultraviolet shot of the same spot on the Martellus map. Also, notice how this map doesn't have sea monsters, but rather banners filled with text.

India

Martellus used different inks on his map, which the researchers revealed with different ranges on the light spectrum.

Different pigments

Here is the same portion of India, but under a different range of light.

"The fact that Martellus wrote some of the texts using different pigments, and those pigments respond differently to light, so they appear with one processing technique, but not with another," said said the project's leader Chet Van Duzer, a board member of the multi-spectral imaging group known as The Lazarus Project at the University of Rochester in New York. This complicated the study of the map considerably, since there was no single processing technique that would reveal all of the text."

Another perspective

Another look at India.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus