What Caused This Man's Scalloped Pupil?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

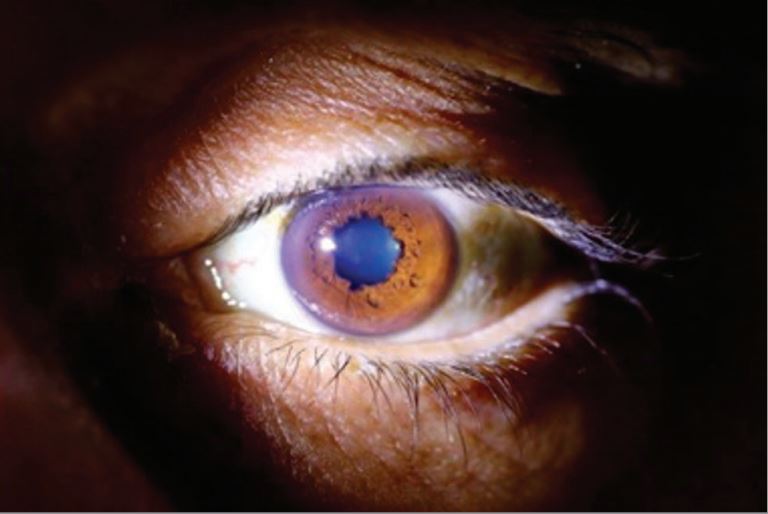

The 46-year-old man's symptoms were concerning but not particularly strange: He was losing weight, experiencing episodes of fainting and having trouble walking. But when doctors examined his eyes, they saw something odd: One of his pupils was smaller than the other, and it had an unusual, scalloped shape with irregular edges.

The strange shape of the man's pupil turned out to be due to a rare genetic condition, according to a new report of the case.

Nearly two decades earlier, when the man was 29, he had a liver transplant to treat a genetic condition called familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP), according to the report, published July 30 in the journal JAMA Neurology.

This condition causes abnormal deposits of a substance called amyloid to build up in the body's tissues and organs, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine(NLM). These deposits most frequently occur in the peripheral nervous system, or the nerves that connect the brain and spinal cord to muscles and cells that detect sensations throughout the body. As a result, the deposits often lead to a loss of sensation in the extremities, the NLM says, but the condition can also affect other systems and organs, including the heart, kidneys, eyes and gastrointestinal tract. ['Eye' Can't Look: 9 Eyeball Injuries That Will Make You Squirm]

In this man's case, the deposits consisted of a protein called transthyretin, which is produced mainly by the liver, according to the new report, from doctors at the Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg.

Because of this, a liver transplant is recommended as the "gold standard" of care for patients with this form of FAP, according to the National Institutes of Health's Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. A liver transplant can slow or halt the progression of neurological symptoms. But this protein is also produced in other parts of the body, including the eye, which means that even with a liver transplant, patients may still experience symptoms, including eye problems.

In patients with this type of FAP, the odd shape of the pupil results from two factors: amyloid deposits in the lens of the eye and abnormalities in the autonomic nervous system (the system that controls involuntary body functions), said Dr. Mark Fromer, an ophthalmologist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, who was not involved with the man's case. Both of these problems result from the underlying genetic condition.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fromer added that this condition is "extremely rare" and that the last time he saw a case like this was around 35 years ago, during his ophthalmology training.

Other eye problems that can result from FAP include severely dry eyes and secondary glaucoma, or glaucoma that results from an increase in eye pressure. There's no cure for eye problems tied to FAP, although doctors can treat symptoms such as dry eye and secondary glaucoma, Fromer told Live Science. The pupil abnormalities would not be treated, he said.

In the man's case, doctors found that FAP had also led to a heart condition, which was causing him to faint. His heart condition was treated with a pacemaker, the report said.

The man's weight loss and walking problems turned out to be due to psychiatric factors unrelated to his genetic condition, including depression and alcohol use disorder. These symptoms went away after the man received psychiatric treatment and cut back on his alcohol consumption, the report said. Three years later, at age 49, the patient remained in stable condition, the report said.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus