Do Hundreds of Earthquakes in Hawaii Mean Kilauea Could Blow?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

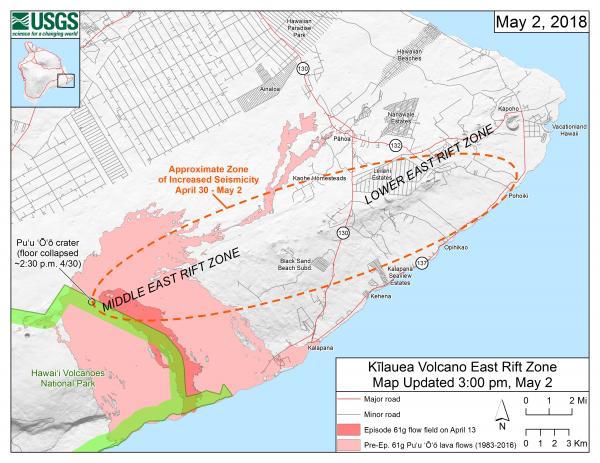

More than 600 earthquakes have rattled Hawaii's Big Island since Monday as red-hot magma from the Kilauea volcano roils underground, moving underneath residential areas, a region where magma hasn't historically traveled, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

What this wayward magma will do is anyone's guess.

"That's the million-dollar question," Janet Babb, a geologist and Hawaiian Volcano Observatory spokesperson, told Live Science. "Magma can intrude in an area and never reach the surface. But an intrusion of magma can also result in an eruption." [Explosive Images: Hawaii's Kilauea Erupts for 30 Years]

As of 8 a.m. local time today (May 3), the Hawaii County Civil Defense Agency reported that while low-magnitude earthquakes continue to shake the area, the situation is slightly less dire than it was yesterday, and that "an eruption is possible but not imminent."

The earth-shaking magma's trip to a residential area may be unexpected, but the Big Island is no stranger to volcanic eruptions. That's because the island of Hawaii is home to Kilauea, a shield-shaped volcano that was formed by successive lava eruptions.

Nowadays, Kilauea has two active vents, places where underground molten lava reaches the surface. One vent is called Pu'u 'Ō'ō, located on the volcano's east rift zone, and the other is located at the volcano's summit, Babb said. Pu'u 'Ō'ō is world famous because it has erupted nearly continuously since January 1983, Babb added.

However, in mid-March, Pu'u 'Ō'ō did something unexpected: It began to inflate, meaning it swelled as magma built up, much like a chef pumps cream into a cream puff, Babb said. As it inflated, Pu'u 'Ō'ō's crater rose higher and higher.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Those signals told us change was afoot," Babb said.

Eventually, there was so much magma in the system that Pu'u 'Ō'ō's crater floor collapsed on Monday (April 30). In the past, excess magma has pierced through the crust to reach the surface at or near Pu'u 'Ō'ō, Babb said. But this time, the magma moved elsewhere — about 10 miles (16 kilometers) southeast of the east rift zone. It moved so far, it's now underneath the Puna District, one of the fastest-growing residential areas on the Big Island.

This roving magma had created several small ground cracks on roads around Leilani Estates, a residential subdivision, the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory reported. However, no steam or heat is coming out of the cracks. Rather, it appears that the intruding magma deformed the ground, which caused the cracks.

It's possible that the lava underneath the Puna District could surface, which is why the "Hawaii County Civil Defense is asking people to exercise vigilance and to be prepared for the possibility of an eruption," Babb said.

Meanwhile, the National Park Service has closed to the public nearly 16,000 acres (6,400 hectares) — an area larger than 12,000 football fields — from the Pu'u 'Ō'ō vent to the Pacific Ocean in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park because of potential volcanic hazards.

The USGS continues to monitor the situation closely, Babb said. To check for updates, go to the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory Status Report or check the USGS Volcanoes Facebook page.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus