This Eerie, Human-Like Figure Is Twice As Old As Egypt's Pyramids

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A towering, human-like figure carved from wood and discovered in a Russian peat bog is more than twice as old as the Egyptian pyramids, scientists have found.

Gold miners discovered pieces of the elongated structure, dubbed the Shigir Idol, in 1894. But it wasn't until about 100 years later, in the late 1990s, that researchers did radiocarbon dating and found that the structure was about 9,900 years old, making it the oldest wooden monumental sculpture in the world, the researchers said.

But this dating wasn't reliable because it included only two pieces from the idol. So scientists recently did a more exhaustive analysis and discovered that the idol is much, much older than previously thought — about 11,500 years old — meaning it was constructed just after the last ice age ended. [25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

This date makes the Shigir Idol more than double the age of the Great Pyramid of Egypt, which was built in about 2550 B.C.

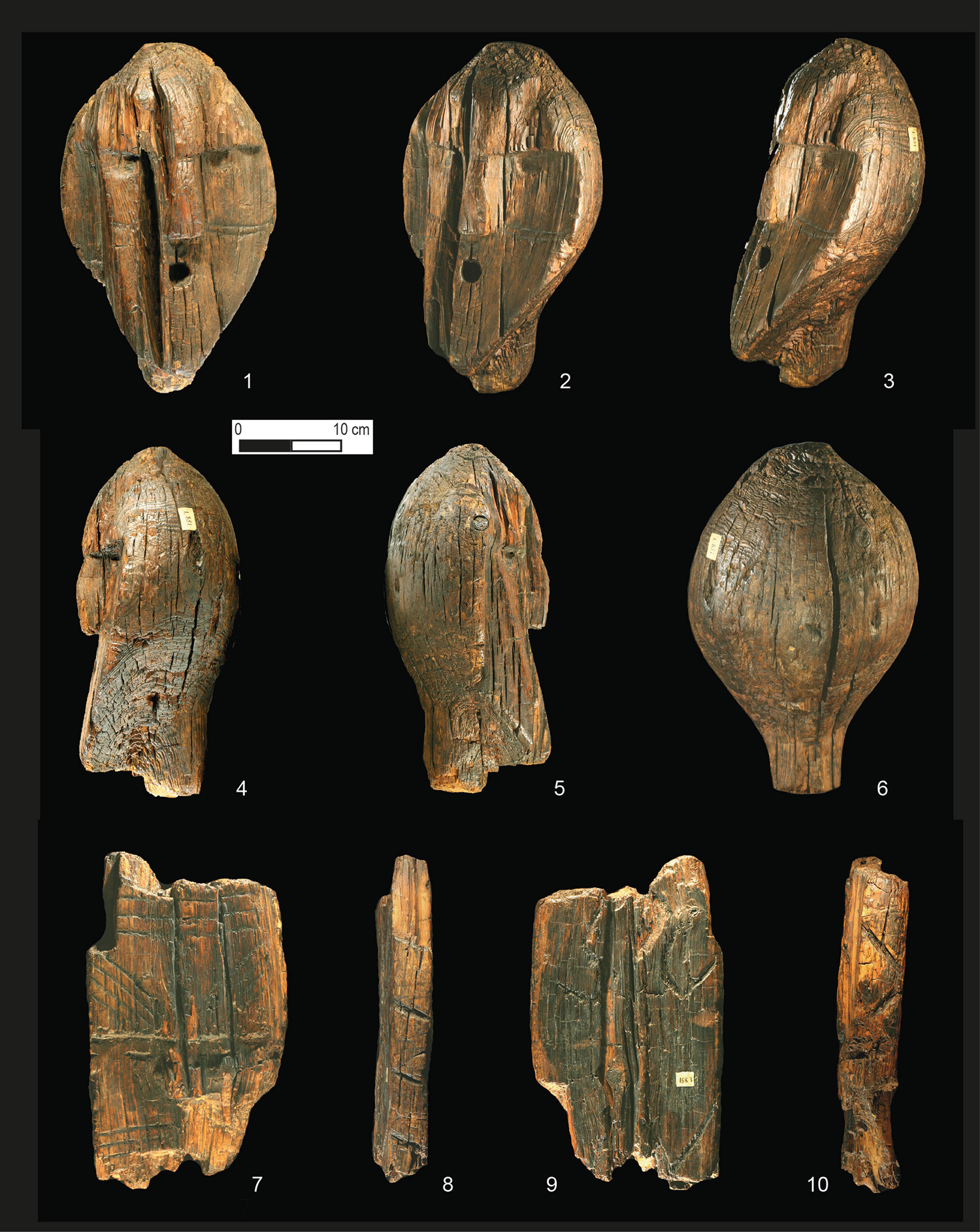

In addition to updating the sculpture's birthday, the researchers found a previously unknown face carved into it, said study co-researcher Thomas Terberger, an archaeologist at the State Agency for Heritage Service of Lower Saxony, in Hannover, Germany.

Incredible find

It's a "miracle" that the Shigir Idol survived all this time, Terberger told Live Science. Researchers began studying the larch-carved figure after it was found in the Shigir peat bog, in Russia's Middle Ural Mountains. Pieced together, the sections of the humanoid idol stood more than 17 feet (5 meters) high.

Unfortunately, some of those sections have since been lost, so the idol now stands about 11.1 feet (3.4 m) high, Terberger said. The public can see the carved anthropomorphic figure at the Sverdlovsk Regional Museum.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

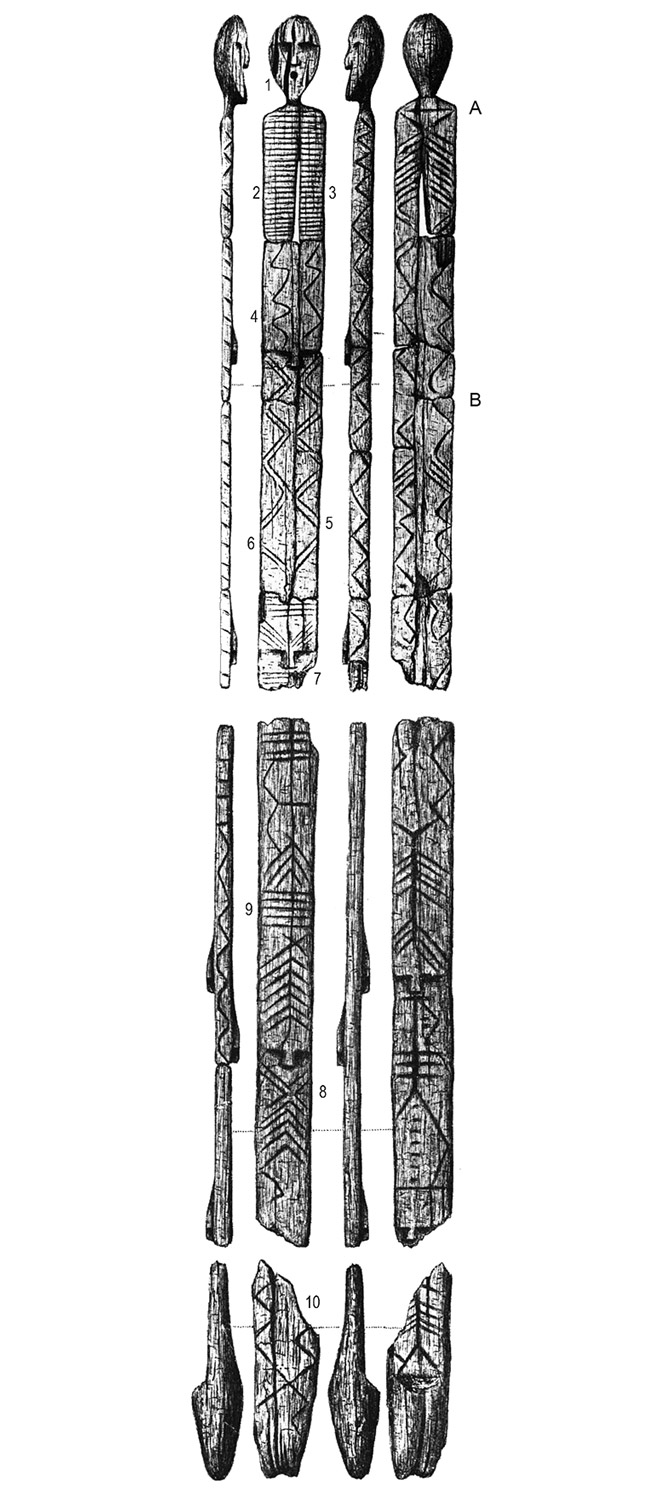

"When I visited the Sverdlovsk Regional Museum for the first time, I was completely surprised by seeing this large wooden sculpture on display in the exhibition," Terberger said. "If you come closer to the sculpture, you will notice that the 'body' is decorated by geometric ornamentation and a few small human faces."

Some 20 years after it was discovered, researcher Vladimir Yakovlevich Tolmachev drew illustrations of the idol, noting the structure's five faces, the researchers of the new study noted. In 2003, a sixth, animal-like face with a rectangular nose was found by study co-researcher Svetlana Savchenko, a scientist at the Sverdlovsk Regional Museum.

Just like a hidden-pictures game, the idol surprised researchers again in 2014, when Savchenko and lead study researcher Mikhail Zhilin, an archaeologist at the Institute of Archaeology in Moscow, discovered a seventh face concealed in the gnarled wood.

These facial findings show that the early hunters, gatherers and fishers of Eurasia were making what was possibly spiritual art during the early Mesolithic, the researchers said.

"Such a big sculpture was well visible for the hunter-gatherer community and might have been important to demonstrate their ancestry," Terberger said. "It is also possible that it was connected to specific myths and gods, but this is difficult to prove."

Terberger noted that many researchers studying early humans focus on the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East. But the Shigir Idol indicates that these researchers should widen their search, given the "unexpected, complex monumental wooden art objects" of the Ural Mountains, he said.

The study was published online today (April 25) in the journal Antiquity. The research was made possible by Natalia Vetrova, the director of the Sverdlovsk Regional Museum, Terberger added.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus