Lab 'Accident' Becomes Mutant Enzyme That Devours Plastic

Scientists accidentally created an enzyme that has an appetite for … plastic, the pervasive kind that's used to make bottles for water and soda, and which can normally take hundreds of years to degrade.

It all began when researchers took a closer look at the crystal structure of a recently discovered enzyme called PETase, which evolved naturally and was already known to break down and digest plastic made of polyethylene terephthalate (PET).

But their investigation had an unlikely result — they introduced a mutation to PETase. The result was a new type of enzyme that digests plastic more efficiently than the original. The improvement was small, but it hinted at the possibility of tweaking plastic-devouring enzymes to dramatically increase their "appetite" for PET, the scientists reported in a new study. [In Images: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch]

"Serendipity often plays a significant role in fundamental scientific research, and our discovery here is no exception," John McGeehan, a professor of structural biology at the University of Portsmouth in the U.K., said in a statement.

PETase was first detected in the bacterium Ideonella sakaiensis, which used the enzyme to munch on plastic in the soil of a PET bottle-recycling facility in Japan, according to the study. The scientists think that enzyme's function in the distant past was to break down a waxy coating on plants. And so the researchers were interested in finding out how the enzyme may have evolved from digesting plant material to plastic.

But, during their exploration, they tweaked the enzyme's structure enough to improve the enzyme's plastic consumption, the scientists wrote in the study.

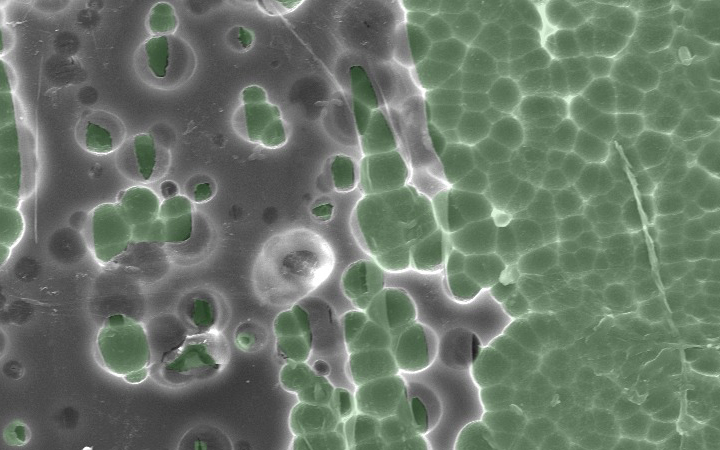

PETase doesn't work very quickly — at least, not quickly enough to put a dent in the plastic garbage accumulating worldwide. While the newcomer mutant enzyme works somewhat more quickly than PETase does, its more important feature lies in its ability to consume another type of plastic: polyethylene furandicarboxylate (PEF), "literally drilling holes through the PEF sample," study co-author Gregg Beckham, a senior engineer at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), said in a statement issued by NREL.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, even the most voracious plastic-eating enzyme will have a lot of plastic trash to plow through before it goes hungry. Humans have loaded down the planet with an estimated 9 billion tons (8.3 billion metric tons) of plastic, half of which has been produced since 2004, Live Science previously reported.

The new findings suggest that it may be possible to solve the global problem of plastic pollution by introducing human-engineered improvements to an enzyme that is already adept at consuming plastics (such as the mutant PETase) — and further work with this enzyme (and its mutant cousins) could make them even more efficient plastic eaters, the study authors reported.

"Given these results, it’s clear that significant potential remains for improving its activity further," study co-author Nicholas Rorrer, a postdoctoral researcher at NREL, said in the NREL statement.

The findings were published online April 16 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.