'Demonic' Fish Glows in Eerie Photo

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

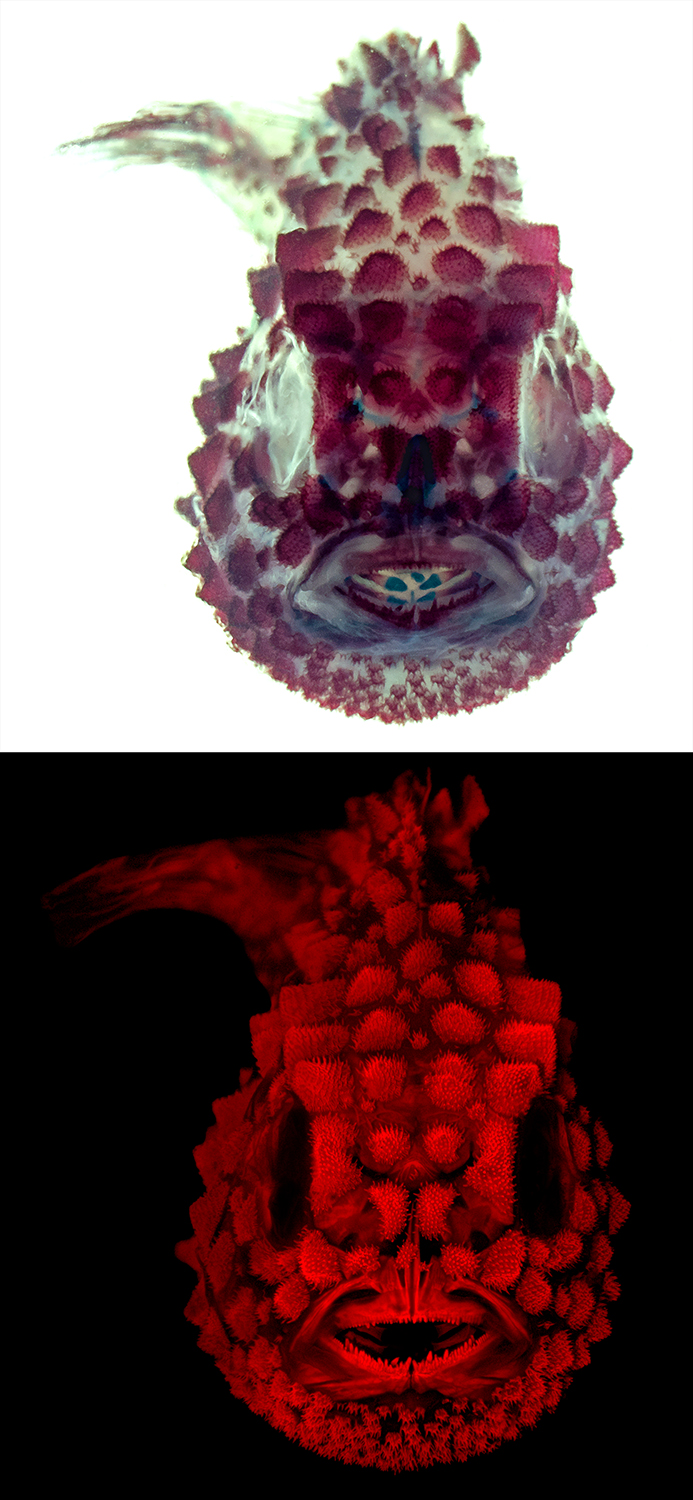

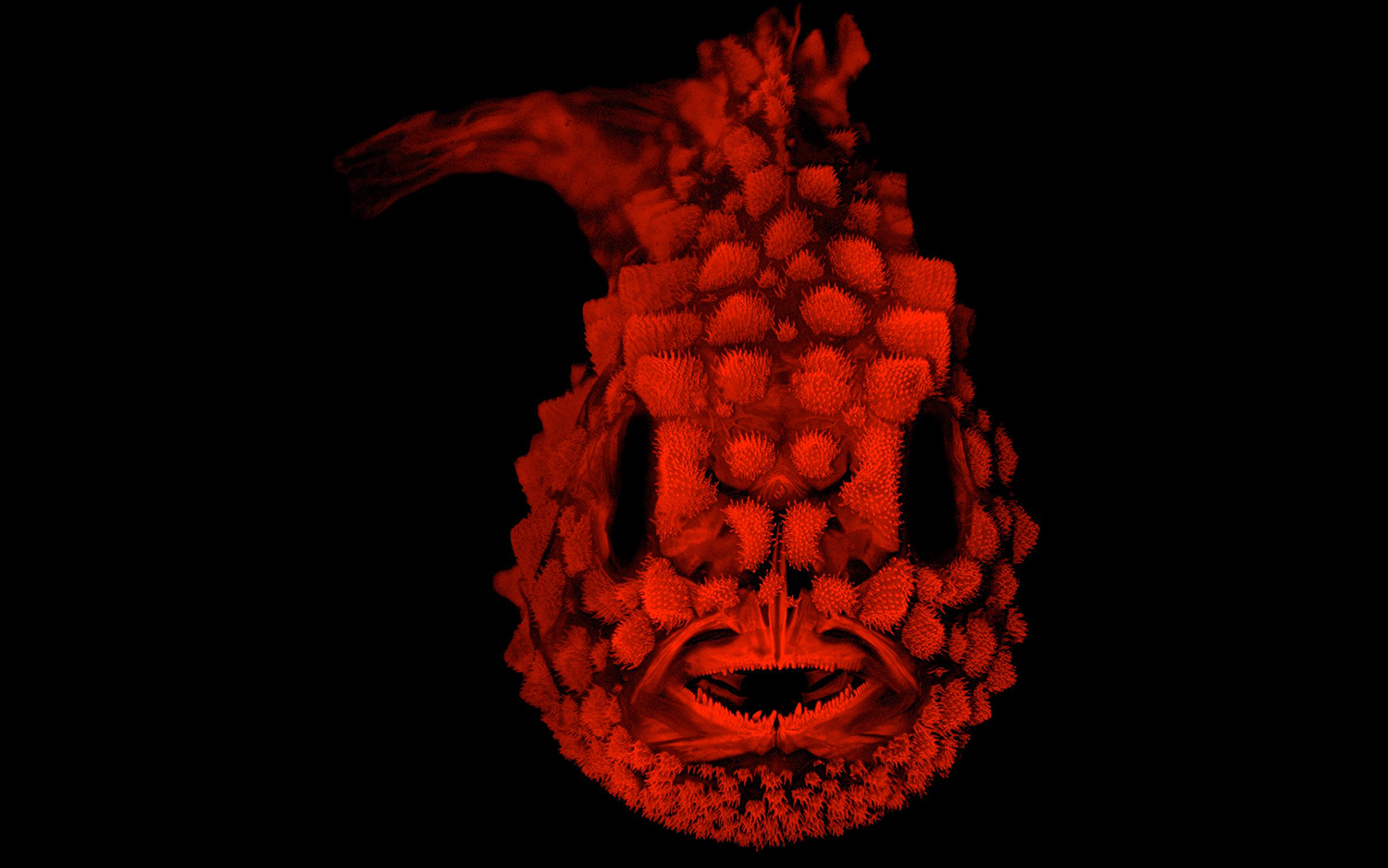

It's an unsettling image that seems more suited to a conversation about demonology than one about marine biology.

An armor-studded fish skeleton, its empty eye sockets fixed upon observers with a baleful stare, glows red under fluorescent light and against a black background, in a photo recently captured and shared on Twitter by Leo Smith, an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at The University of Kansas.

But the fish is no demon, and the image wasn't crafted in Photoshop or using digital manipulation — the color, glow and spiky studs that line the fish's bones are all normal features of an aquatic oddball called the Pacific spiny lumpsucker (Eumicrotremus orbis), Smith told Live Science. [Photos: The Freakiest-Looking Fish]

Pacific spiny lumpsuckers — when they're alive — are genuinely adorable. They're small and rotund, bearing a distinct resemblance to a spiky, bug-eyed golf ball. The common name is an apt description of the tiny fish, calling attention to their Pacific Ocean habitat, their coat of bony lumps — known as tubercles — and a large sucker on their stomachs that helps them cling to rocks, according to the Aquarium of the Pacific.

But though they may look endearing, you don't want to touch them — "holding one is like holding a small cactus," Smith said. Their tubercles are highly modified fish scales that also include some bony material, and they are likely used as a defense against predators. Tubercles are found in many types of fish, but they are a common feature in lumpsuckers — a group that includes about 28 species — and snailfish, a group of deep-sea-dwelling fish with about 430 species, Smith said.

Many fish are known to naturally fluoresce — re-emit reflected light — in certain parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. Smith wanted to capture the Pacific spiny lumpsucker's unusual skeleton — which is particularly spiny, as lumpsuckers go — as it fluoresced red under his microscope, which had special filtering attachments to mask everything except the specimen's fluorescence, he told Live Science.

"The specimen lights itself, and everything else in the image disappears," he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ready for a "demonic" close-up

To reveal the fish's bumpy bones and unleash its "demonic" side for the image, Smith used a process called clearing and staining. First, he immersed the fish in a bath of cow-stomach enzymes to digest the muscle but leave the connective tissue intact, thereby rendering the flesh transparent so that the bones were visible.

Once "cleared," a specimen's skeleton and cartilage can then be stained with colorful dyes. This way, all the bones are still encased in flesh and in their correct positions, so they can move the way they normally would in a living animal, Smith said.

But arranging the fish in a camera-facing posture was tricky — with all its muscle dissolved away, the fish was too floppy to hold a pose. Smith experimented with suspending the fish in different liquids, landing on a mixture that combined gelatin and glycerin into a gooey, gluey slop that was "gross to touch," but it hardened enough to hold the fish in place while he photographed it.

The results captured the structure of the Pacific spiny lumpsucker's tubercles in astonishing detail. Large bumps surround the fish's eyes and extend down its back, while much smaller lumps cover its belly and sprout in the spaces between the big bumps. In the photo, the surface of each bump appears to be covered in many smaller spikes that would certainly make a predator think twice about taking a bite.

But even though Smith labeled the fish "pretty demonic" in his tweet, he admitted that the most striking thing about wee Pacific spiny lumpsuckers is that people love them "just because they're adorable," he told Live Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus